Gerry Anderson's much maligned and somewhat underrated 1970s British science fiction television series Space: 1999 spawned a very extensive series of spin-off novels including quite a few original novels, which included E.C. Tubb’s Alien Seed which appeared in 1976.

Alien Seed is one of the more successful TV tie-in novels that I’ve read so far. It’s slightly more serious in tone than the television series but it still manages to feel like a genuine Space: 1999 story. It’s quite ambitious, it's reasonably intelligent and on the whole I think it can be said that it's a succees. It’s definitely worth checking out. Here’s the link to my review at Cult TV Lounge.

pulp novels, trash fiction, detective stories, adventure tales, spy fiction, etc from the 19th century up to the 1970s

Saturday, June 30, 2018

Tuesday, June 26, 2018

Still Dead by Ronald Knox

Still Dead was the fourth of the Miles Bredon mysteries written by Monsignor Ronald Knox (1888-1957). It was published in 1934.

Donald Reiver is the laird of Dorn in the Scottish Lowlands. His heir is his son Colin, and a less worthy heir would be difficult to imagine. His only real usefulness to the family is that his life has been insured, with the Indescribable Insurance Company, for a very large sum. Donald has been for many years estranged from his brother, Major Henry Reiver.

The family’s troubles seem to be multiplying. Young Colin’s growing dissipation has had fatal consequences - driving his car while the worse for drink he has run over and killed the son of the estate’s head gardener. And Donald has taken a chill and is dangerously ill. Ill enough to make it advisable to make his will. The will may well be a bone of contention - Donald has decided to leave everything to a religious sect that he has recently joined. This won’t effect the estate, which is entailed, but if Colin were to predecease Donald then the money from that insurance policy would go to the sect.

And now the gamekeeper has found a dead body by the roadside.

The puzzle here is not the cause of death. The Procurator Fiscal (this being Scotland there is no coroner’s inquest) is perfectly satisfied that the death was due to natural causes. The puzzle concerns the date of the victim’s death. Was the body discovered on the Monday, or on the Wednesday? Because, amazing as it may seem, there is genuine doubt on this point. And that explains the Indescribable Insurance Company’s keen interest in the matter. If the victim died on the Wednesday there is no problem and the claim will be paid. If however he died on the Monday then it’s a different matter, since on the Monday the premium had not been paid and the policy was technically not in force. Not surprisingly the Indescribable has asked their ace investigator Miles Bredon to look into the matter.

Miles sets off for Scotland, accompanied as usual by his wife Angela (Miles and Angela Bredon being one of the more likeable husband-and-wife teams in detective fiction). The date of death turns out to be a very real puzzle. The victim was certainly dead on the Wednesday. As to the Monday, the evidence is very contradictory and incomplete. While there’s no evidence to suggest murder there is the definite possibility that someone may have had a motive for moving or concealing the body and for generally muddying the waters about the date. And while there’s no reason to suspect murder Miles has to admit that there are a couple of things that worry him about this case. That torch battery worries him a good deal.

Of course some of the locals have their own explanation - it’s obvious that the gamekeeper has second sight. The initial discovery of the body was a preternatural event, and perfectly in keeping with the known fact of the Reiver family curse.

Knox was an extremely witty writer and his detective novels always have a delightfully amusing quality but he was also a firm believer in sound and disciplined plotting (he was after all the author of the famous Ten Commandments for Detective Fiction). He does some very clever stuff with clues in this book but I can’t say any more for fear of spoilers.

The book also includes footnote links to all the clues so when you get to the solution you can check back to make sure the author hasn’t been cheating!

That solution may not please all readers, being just a little unconventional.

Despite being a priest Knox was not the kind of writer to bludgeon the reader with his moral views. For Knox the writing of detective stories was a pleasant diversion and a stimulating intellectual exercise rather than an opportunity for preaching. Of course you cannot entirely eliminate morality from the detective story which is a type of fiction that is entirely dependent on a belief that there are such things as right and wrong. This novel does raise some moral issues but to the extent that they’re resolved they’re resolved in a surprisingly open-ended way.

Still Dead makes use of a number of tropes that are going to be pretty familiar to fans of golden age mysteries but Knox throws in enough twists to keep things interesting. Knox is always a joy to read. His style is light-hearted but he avoids the peril of indulging in whimsy.

I thoroughly enjoyed Still Dead. Perhaps not as ingenious as The Three Taps or The Footsteps at the Lock but still highly recommended.

Donald Reiver is the laird of Dorn in the Scottish Lowlands. His heir is his son Colin, and a less worthy heir would be difficult to imagine. His only real usefulness to the family is that his life has been insured, with the Indescribable Insurance Company, for a very large sum. Donald has been for many years estranged from his brother, Major Henry Reiver.

The family’s troubles seem to be multiplying. Young Colin’s growing dissipation has had fatal consequences - driving his car while the worse for drink he has run over and killed the son of the estate’s head gardener. And Donald has taken a chill and is dangerously ill. Ill enough to make it advisable to make his will. The will may well be a bone of contention - Donald has decided to leave everything to a religious sect that he has recently joined. This won’t effect the estate, which is entailed, but if Colin were to predecease Donald then the money from that insurance policy would go to the sect.

And now the gamekeeper has found a dead body by the roadside.

The puzzle here is not the cause of death. The Procurator Fiscal (this being Scotland there is no coroner’s inquest) is perfectly satisfied that the death was due to natural causes. The puzzle concerns the date of the victim’s death. Was the body discovered on the Monday, or on the Wednesday? Because, amazing as it may seem, there is genuine doubt on this point. And that explains the Indescribable Insurance Company’s keen interest in the matter. If the victim died on the Wednesday there is no problem and the claim will be paid. If however he died on the Monday then it’s a different matter, since on the Monday the premium had not been paid and the policy was technically not in force. Not surprisingly the Indescribable has asked their ace investigator Miles Bredon to look into the matter.

Miles sets off for Scotland, accompanied as usual by his wife Angela (Miles and Angela Bredon being one of the more likeable husband-and-wife teams in detective fiction). The date of death turns out to be a very real puzzle. The victim was certainly dead on the Wednesday. As to the Monday, the evidence is very contradictory and incomplete. While there’s no evidence to suggest murder there is the definite possibility that someone may have had a motive for moving or concealing the body and for generally muddying the waters about the date. And while there’s no reason to suspect murder Miles has to admit that there are a couple of things that worry him about this case. That torch battery worries him a good deal.

Of course some of the locals have their own explanation - it’s obvious that the gamekeeper has second sight. The initial discovery of the body was a preternatural event, and perfectly in keeping with the known fact of the Reiver family curse.

Knox was an extremely witty writer and his detective novels always have a delightfully amusing quality but he was also a firm believer in sound and disciplined plotting (he was after all the author of the famous Ten Commandments for Detective Fiction). He does some very clever stuff with clues in this book but I can’t say any more for fear of spoilers.

The book also includes footnote links to all the clues so when you get to the solution you can check back to make sure the author hasn’t been cheating!

That solution may not please all readers, being just a little unconventional.

Despite being a priest Knox was not the kind of writer to bludgeon the reader with his moral views. For Knox the writing of detective stories was a pleasant diversion and a stimulating intellectual exercise rather than an opportunity for preaching. Of course you cannot entirely eliminate morality from the detective story which is a type of fiction that is entirely dependent on a belief that there are such things as right and wrong. This novel does raise some moral issues but to the extent that they’re resolved they’re resolved in a surprisingly open-ended way.

Still Dead makes use of a number of tropes that are going to be pretty familiar to fans of golden age mysteries but Knox throws in enough twists to keep things interesting. Knox is always a joy to read. His style is light-hearted but he avoids the peril of indulging in whimsy.

I thoroughly enjoyed Still Dead. Perhaps not as ingenious as The Three Taps or The Footsteps at the Lock but still highly recommended.

Friday, June 22, 2018

Anthony Wynne's Murder of a Lady

Robert McNair Wilson (1882-1963) was a Scottish doctor who wrote numerous detective novels under the pseudonym Anthony Wynne. Murder of a Lady (AKA The Silver Scale Mystery) was published in 1931.

This is a locked-room mystery. In fact it’s a multiple locked-room mystery.

We start with the murder of Mary Gregor, an elderly lady and the sister of the laird of Duchlan. We are told that Mary Gregor was a saint and did not have an enemy in the world, which naturally leads us to suspect that she was far from being a saint and probably had more than her fair share of enemies. And this proves to be the case.

Her murder took place in a room locked from the inside. The windows were also locked from the inside. Not only that - the grandfather of the current laird had been a keen amateur locksmith and had installed locks of his own fiendishly ingenious design throughout Castle Duchlan. None of the usual methods of defeating the locksmith’s art will have any effect on these locks.

The most puzzling clue is a fish scale. A fish scale is found at the scene of the second murder as well.

Inspector Dundas approaches the case with a good deal of confidence. Even though Dr Hailey, renowned physician and even more renowned amateur criminologist, is on the scene Dundas makes it clear that he does not want any assistance.

Dr Hailey is drawn into the case by his personal interest in two of the chief suspects. Oonagh Gregor is the laird’s daughter-in-law and her name has been linked in local gossip with that of Dr McDonald, who is the local doctor (and in fact the only doctor for miles about). Dr Hailey rescues Oonagh from drowning and he is convinced that she and Dr McDonald are innocent. He also believes that the laird’s son, Captain Eoghan Gregor, is innocent. The only two other possible suspects are the laird himself and Angus, an old and much-loved family retainer, and Dr Hailey thinks they’re innocent as well! The death-blow had such force behind it that the murderer had to be a man.

Neither Dr Hailey nor the police are able to make much headway on solving the locked-room problem and soon they will have another impossible crime puzzle to unravel as well.

The setting, the remote Loch Fyne, is used effectively and there’s extra atmosphere added by the prevalent Highland superstitions. The laird himself seems to think the swimmers may be responsible for the murders, the swimmers being ghostly fish-men who inhabit the loch and are assumed by the locals to be behind all manner of misfortunes and tragedies.

There’s a lot to admire in this book. The mechanisms behind the locked-room mysteries are genuinely clever and even more importantly the explanations are plausible.

On the other hand there are some quite ludicrous elements to the plot. And there’s a great deal of tedious and overheated romantic and emotional melodrama.

Generally speaking I think it’s a mistake for a writer of detective fiction to bother too much about characterisation but if you are going to make that mistake then you should at least try to make the characters vaguely believable. The characters in this novel are so exaggerated and the villainies so outrageous and over-the-top that the whole thing becomes silly and unconvincing.

Another problem is that Wynne seems to have such a thorough loathing for Scotland and its inhabitants that it gets a bit embarrassing.

There’s also some truly awful dialogue.

Murder of a Lady gives us a very very good locked-room problem but overall it’s a pretty mediocre book. This one is strictly for really hardcore locked-room fans.

This is a locked-room mystery. In fact it’s a multiple locked-room mystery.

We start with the murder of Mary Gregor, an elderly lady and the sister of the laird of Duchlan. We are told that Mary Gregor was a saint and did not have an enemy in the world, which naturally leads us to suspect that she was far from being a saint and probably had more than her fair share of enemies. And this proves to be the case.

Her murder took place in a room locked from the inside. The windows were also locked from the inside. Not only that - the grandfather of the current laird had been a keen amateur locksmith and had installed locks of his own fiendishly ingenious design throughout Castle Duchlan. None of the usual methods of defeating the locksmith’s art will have any effect on these locks.

The most puzzling clue is a fish scale. A fish scale is found at the scene of the second murder as well.

Inspector Dundas approaches the case with a good deal of confidence. Even though Dr Hailey, renowned physician and even more renowned amateur criminologist, is on the scene Dundas makes it clear that he does not want any assistance.

Dr Hailey is drawn into the case by his personal interest in two of the chief suspects. Oonagh Gregor is the laird’s daughter-in-law and her name has been linked in local gossip with that of Dr McDonald, who is the local doctor (and in fact the only doctor for miles about). Dr Hailey rescues Oonagh from drowning and he is convinced that she and Dr McDonald are innocent. He also believes that the laird’s son, Captain Eoghan Gregor, is innocent. The only two other possible suspects are the laird himself and Angus, an old and much-loved family retainer, and Dr Hailey thinks they’re innocent as well! The death-blow had such force behind it that the murderer had to be a man.

Neither Dr Hailey nor the police are able to make much headway on solving the locked-room problem and soon they will have another impossible crime puzzle to unravel as well.

The setting, the remote Loch Fyne, is used effectively and there’s extra atmosphere added by the prevalent Highland superstitions. The laird himself seems to think the swimmers may be responsible for the murders, the swimmers being ghostly fish-men who inhabit the loch and are assumed by the locals to be behind all manner of misfortunes and tragedies.

There’s a lot to admire in this book. The mechanisms behind the locked-room mysteries are genuinely clever and even more importantly the explanations are plausible.

On the other hand there are some quite ludicrous elements to the plot. And there’s a great deal of tedious and overheated romantic and emotional melodrama.

Generally speaking I think it’s a mistake for a writer of detective fiction to bother too much about characterisation but if you are going to make that mistake then you should at least try to make the characters vaguely believable. The characters in this novel are so exaggerated and the villainies so outrageous and over-the-top that the whole thing becomes silly and unconvincing.

Another problem is that Wynne seems to have such a thorough loathing for Scotland and its inhabitants that it gets a bit embarrassing.

There’s also some truly awful dialogue.

Murder of a Lady gives us a very very good locked-room problem but overall it’s a pretty mediocre book. This one is strictly for really hardcore locked-room fans.

Tuesday, June 19, 2018

The Birds of a Feather Affair - The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. #2

Recently I’ve been exploring the world of TV tie-in novels from the 1960s. Surprisingly even series that had quite short runs spawned tie-in novels and The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. which only lasted a single season (1966-67) gave birth to no less than five original novels, although for some reason three of them were only ever published in Britain.

The Birds of a Feather Affair by Michael Avallone appeared in 1966. It’s notable mostly for differing quite sharply from the television series when it comes to tone. Here's the link to my review on Cult TV Lounge.

The Birds of a Feather Affair by Michael Avallone appeared in 1966. It’s notable mostly for differing quite sharply from the television series when it comes to tone. Here's the link to my review on Cult TV Lounge.

Sunday, June 17, 2018

The Dagger Affair, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. #4

TV tie-in novels might not be one of the more respectable literary genres but then pulp fiction has never been respectable either and that’s never put me off. In fact TV tie-in novels are in some ways a modern version of the Victorian penny dreadfuls and dime novels and early 20th century pulp fiction - pure entertainment with no literary pretensions whatsoever.

I’ve recently found myself developing a mild interest in this ever so slightly disreputable field which ties in neatly with my enthusiasm for cult television of the 1960s and 1970s. I’m going to be posting occasional reviews of such books on my Cult TV Lounge blog, the first cab off the rank being one of the many Man from U.N.C.L.E. tie-in novels. Here’s the link to the fourth of this series of novels, David McDaniel's The Dagger Affair.

I’ve recently found myself developing a mild interest in this ever so slightly disreputable field which ties in neatly with my enthusiasm for cult television of the 1960s and 1970s. I’m going to be posting occasional reviews of such books on my Cult TV Lounge blog, the first cab off the rank being one of the many Man from U.N.C.L.E. tie-in novels. Here’s the link to the fourth of this series of novels, David McDaniel's The Dagger Affair.

Thursday, June 14, 2018

The Budapest Parade Murders

The very considerable literary output (amounting to 78 novels) of American writer Francis Van Wyck Mason (1901-1978) included detective fiction, adventure stories, historical fiction and spy thrillers. This included twenty-six spy novels featuring Captain (later Colonel) Hugh North, a U.S. Army officer assigned to G-2 (Military Intelligence).

The Budapest Parade Murders appeared in 1935 and was the eighth of the Hugh North books.

The action starts on board a train, which is always promising. A daring assassination attempt has taken place on board the Budapest Express. The intended victim is Sir William Woodman, a prominent pacifist on his way to a disarmament conference. Sir William has collected damning evidence in the form of letters that arms manufacturers are actively involved in trying to start another world war. Unfortunately the would-be assassin succeeded in stealing the letters.

By a stroke of good fortune Captain Hugh North just happens to be aboard the Budapest Express. Also aboard is Major Kilgour of British Intelligence. Perhaps less fortunate is the presence of a pushy American newspaperman.

The disarmament conference is now very much endangered but actually it’s worse than that. The assassination has triggered a wave of mutual recriminations and suspicions and has created an atmosphere with sinister echoes of 1914. If those responsible for the outrage on the Budapest Express cannot be exposed it is not impossible that war will be the result. The Hungarian police are happy to have the assistance of both Captain North and Major Kilgour. Undertaking an investigation in a foreign country is obviously tricky, but it’s North’s job to carry out such delicate missions.

Of course it’s not entirely a straightforward criminal investigation. Hugh North certainly has the skills of a detective but he is an American intelligence agent and he must put American interests first. Major Kilgour, being a British intelligence agent, will also doubtless be putting British interests first. And the Hungarian Chief of Police obviously will be concerned about Hungary’s interests. These three men all sincerely want to avoid war but there is considerable potential for conflicts of interest.

The Hugh North spy tales contain their fair share of action but they’re also reasonably gritty and realistic (certainly much more so than many of the other popular spy thrillers of the 20s and 30s). They’re also surprisingly quite cynical. There’s a good deal of corruption in high places and there are plenty of powerful people who would cheerfully start a war if they stood to gain by it. While North is definitely a patriotic American he is realistic enough to accept the reality that America does not always have entirely clean hands, and that Americans can be as corrupt as anyone else. Diplomacy and espionage are tough games that are played without any concern for morality.

North is more a counter-espionage agent than a spy and he uses some of the techniques of the detective. There is a puzzle to be solved here. The identity of the assassin, and of the assassin’s accomplices, must be established and North has several clues that may help. He found a monocle and some tiny fragments of paper in the compartment in which Sir William was attacked.

In fact it’s structurally rather in the mode of the classic golden age detective story, and it even includes a floor plan! Mostly it’s the unravelling of a murder mystery but with thriller moments to add excitement and with the murder having implications for the fate of the whole world. Hugh North’s plan to unmask the villain involves bringing all the suspects together at a supper party in a palace - exactly the kind of thing you’d expect Hercule Poirot or Ellery Queen to come up with.

There are obviously none of the high-tech electronic gadgets that would become a feature of post-WW2 spy fiction but North does make use of science and technology, and there are what a few years earlier would have been described as infernal machines.

There are also deadly women. Quite a few deadly women. Some might be spies, some might be adventuresses, some might be femmes fatales. Pretty much all the female characters can be assumed to be potentially dangerous. Of course the same assumption can be made about pretty much all the male characters as well.

The political background is quite intriguing. This novel was written in 1935. There were international tensions, there are always international tensions, but the new regime in Germany was not yet regarded as a major threat. Nor was Japan seen as an especially significant threat. The possibility of war is therefore somewhat nebulous. Mutual mistrust between Britain and the United States over naval and imperial rivalry seems to be a bigger issue than Germany (and in reality both the British and U.S. navies were making plans in the 1920s for a possible Anglo-American naval war). The fact that the book doesn’t focus exclusively on a single major threat to peace makes it rather interesting.

In fact the biggest international evil in this story is not represented by governments but by arms manufacturers (and the politicians they have corrupted). This might make it sound like a socialist or pacifist tract but it isn’t. North is just a straightforward patriot who has fought in one war and is hoping not to have to fight in another.

The spy fiction of the interwar years was quite varied, ranging from pure boys’ own adventure fantasy stuff (like the Bulldog Drummond stories) to the darkness and cynicism of Eric Ambler. The Budapest Parade Murders is somewhere in the middle. It’s more realistic than Bulldog Drummond stories but not as grim or nihilistic as Ambler or Greene, and it’s not quite a pure thriller and not quite a pure mystery. It is entertaining though. It’s recommended, as is his earlier The Branded Spy Murders.

The Budapest Parade Murders appeared in 1935 and was the eighth of the Hugh North books.

The action starts on board a train, which is always promising. A daring assassination attempt has taken place on board the Budapest Express. The intended victim is Sir William Woodman, a prominent pacifist on his way to a disarmament conference. Sir William has collected damning evidence in the form of letters that arms manufacturers are actively involved in trying to start another world war. Unfortunately the would-be assassin succeeded in stealing the letters.

By a stroke of good fortune Captain Hugh North just happens to be aboard the Budapest Express. Also aboard is Major Kilgour of British Intelligence. Perhaps less fortunate is the presence of a pushy American newspaperman.

The disarmament conference is now very much endangered but actually it’s worse than that. The assassination has triggered a wave of mutual recriminations and suspicions and has created an atmosphere with sinister echoes of 1914. If those responsible for the outrage on the Budapest Express cannot be exposed it is not impossible that war will be the result. The Hungarian police are happy to have the assistance of both Captain North and Major Kilgour. Undertaking an investigation in a foreign country is obviously tricky, but it’s North’s job to carry out such delicate missions.

Of course it’s not entirely a straightforward criminal investigation. Hugh North certainly has the skills of a detective but he is an American intelligence agent and he must put American interests first. Major Kilgour, being a British intelligence agent, will also doubtless be putting British interests first. And the Hungarian Chief of Police obviously will be concerned about Hungary’s interests. These three men all sincerely want to avoid war but there is considerable potential for conflicts of interest.

The Hugh North spy tales contain their fair share of action but they’re also reasonably gritty and realistic (certainly much more so than many of the other popular spy thrillers of the 20s and 30s). They’re also surprisingly quite cynical. There’s a good deal of corruption in high places and there are plenty of powerful people who would cheerfully start a war if they stood to gain by it. While North is definitely a patriotic American he is realistic enough to accept the reality that America does not always have entirely clean hands, and that Americans can be as corrupt as anyone else. Diplomacy and espionage are tough games that are played without any concern for morality.

North is more a counter-espionage agent than a spy and he uses some of the techniques of the detective. There is a puzzle to be solved here. The identity of the assassin, and of the assassin’s accomplices, must be established and North has several clues that may help. He found a monocle and some tiny fragments of paper in the compartment in which Sir William was attacked.

In fact it’s structurally rather in the mode of the classic golden age detective story, and it even includes a floor plan! Mostly it’s the unravelling of a murder mystery but with thriller moments to add excitement and with the murder having implications for the fate of the whole world. Hugh North’s plan to unmask the villain involves bringing all the suspects together at a supper party in a palace - exactly the kind of thing you’d expect Hercule Poirot or Ellery Queen to come up with.

There are obviously none of the high-tech electronic gadgets that would become a feature of post-WW2 spy fiction but North does make use of science and technology, and there are what a few years earlier would have been described as infernal machines.

There are also deadly women. Quite a few deadly women. Some might be spies, some might be adventuresses, some might be femmes fatales. Pretty much all the female characters can be assumed to be potentially dangerous. Of course the same assumption can be made about pretty much all the male characters as well.

The political background is quite intriguing. This novel was written in 1935. There were international tensions, there are always international tensions, but the new regime in Germany was not yet regarded as a major threat. Nor was Japan seen as an especially significant threat. The possibility of war is therefore somewhat nebulous. Mutual mistrust between Britain and the United States over naval and imperial rivalry seems to be a bigger issue than Germany (and in reality both the British and U.S. navies were making plans in the 1920s for a possible Anglo-American naval war). The fact that the book doesn’t focus exclusively on a single major threat to peace makes it rather interesting.

In fact the biggest international evil in this story is not represented by governments but by arms manufacturers (and the politicians they have corrupted). This might make it sound like a socialist or pacifist tract but it isn’t. North is just a straightforward patriot who has fought in one war and is hoping not to have to fight in another.

The spy fiction of the interwar years was quite varied, ranging from pure boys’ own adventure fantasy stuff (like the Bulldog Drummond stories) to the darkness and cynicism of Eric Ambler. The Budapest Parade Murders is somewhere in the middle. It’s more realistic than Bulldog Drummond stories but not as grim or nihilistic as Ambler or Greene, and it’s not quite a pure thriller and not quite a pure mystery. It is entertaining though. It’s recommended, as is his earlier The Branded Spy Murders.

Friday, June 8, 2018

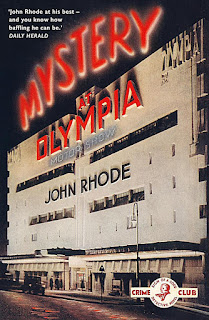

John Rhode's Mystery at Olympia

Mystery at Olympia (AKA Murder at the Motor Show) is a 1935 Dr Priestley mystery written by Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1964) under the name John Rhode.

At the Olympia Motor Show, in an immense crowd gathered around Stand 1001 to see the new and revolutionary touring car from the Comet Motor Company, an elderly man collapses and dies. This happens more or less right in front of Dr Priestley’s old friend Dr Oldland, whose efforts to save the man are unavailing. The elderly man is Nahum Pershore, a rather wealthy speculative builder.

At almost the same moment a pretty young parlourmaid in Mr Pershore’s household is taken violently ill. A Dr Formby is called in and he immediately suspects arsenic poisoning.

The post mortem on Mr Pershore raises more questions than it answers. Some very odd things have clearly been going on at the Pershore residence and it’s obvious that someone didn’t like Nahum Pershore. What is not obvious is whether he was murdered or not, and if so how.

In a John Rhode mystery you expect some cleverness when it comes to the method of despatching the murder victim or victims. In this book the author plays a number of different games with murder methods.

You also expect that science will play some part in the crime and in the solution. And in this instance there are some esoteric matters of forensic medicine involved.

This is also arguably an impossible crime story. There’s a man who is dead but he has no right to be. And what was a man who had zero interest in cars doing at a motor show?

As to the solution, there is perhaps a slight plausibility problem.

As usual it’s Superintendent Hanslet who does most of the investigating. He’s the principal detective character with Dr Priestley remaining in the background. And as usual Hanslet is wrong on just about every point. He has a great enthusiasm for constructing elaborate theories and a lack of evidence to support those theories is something he really doesn’t worry about. Priestley’s interpretations of the evidence are of course very much sounder. And while Dr Priestley appears to be taking no active part in the investigation this is not quite the case. He is constantly feeding Hanslet hints that, with luck, will eventually put the superintendent on the right track.

Hanslet is dogged and he’s thorough but I have to say that I would be very very worried if I happened to be an innocent person who was a suspect in one of his investigations. Superintendent Hanslet’s powers of imagination are impressive but his powers of detection leave quite a lot to be desired.

It became increasingly rare for Priestley to go out into the field so to speak. He came to prefer sitting in comfort in his own home whilst pulling the strings of the police investigation. In his 1930s mysteries he was more inclined to take an active role when he considered it to be absolutely essential. In this case he does pay a visit to the Motor Show in order to confirm a very strong suspicion.

Mystery at Olympia contains most of the ingredients that John Rhode fans tend to enjoy - exotic murder methods, some fun with alibis, questions about wills, some esoteric forensic science and an enthusiasm for technology (the author was clearly a bit of a motoring buff). Dr Priestley is his usual mercilessly unsentimental self (with a characteristic touch of ruthlessness at the end). Whether the book stretches credibility a bit too far in one key element is up to the reader to decide.

On the whole I highly recommend this one. And it’s readily available in an affordable brand new paperback edition!

At the Olympia Motor Show, in an immense crowd gathered around Stand 1001 to see the new and revolutionary touring car from the Comet Motor Company, an elderly man collapses and dies. This happens more or less right in front of Dr Priestley’s old friend Dr Oldland, whose efforts to save the man are unavailing. The elderly man is Nahum Pershore, a rather wealthy speculative builder.

At almost the same moment a pretty young parlourmaid in Mr Pershore’s household is taken violently ill. A Dr Formby is called in and he immediately suspects arsenic poisoning.

The post mortem on Mr Pershore raises more questions than it answers. Some very odd things have clearly been going on at the Pershore residence and it’s obvious that someone didn’t like Nahum Pershore. What is not obvious is whether he was murdered or not, and if so how.

In a John Rhode mystery you expect some cleverness when it comes to the method of despatching the murder victim or victims. In this book the author plays a number of different games with murder methods.

You also expect that science will play some part in the crime and in the solution. And in this instance there are some esoteric matters of forensic medicine involved.

This is also arguably an impossible crime story. There’s a man who is dead but he has no right to be. And what was a man who had zero interest in cars doing at a motor show?

As to the solution, there is perhaps a slight plausibility problem.

As usual it’s Superintendent Hanslet who does most of the investigating. He’s the principal detective character with Dr Priestley remaining in the background. And as usual Hanslet is wrong on just about every point. He has a great enthusiasm for constructing elaborate theories and a lack of evidence to support those theories is something he really doesn’t worry about. Priestley’s interpretations of the evidence are of course very much sounder. And while Dr Priestley appears to be taking no active part in the investigation this is not quite the case. He is constantly feeding Hanslet hints that, with luck, will eventually put the superintendent on the right track.

Hanslet is dogged and he’s thorough but I have to say that I would be very very worried if I happened to be an innocent person who was a suspect in one of his investigations. Superintendent Hanslet’s powers of imagination are impressive but his powers of detection leave quite a lot to be desired.

It became increasingly rare for Priestley to go out into the field so to speak. He came to prefer sitting in comfort in his own home whilst pulling the strings of the police investigation. In his 1930s mysteries he was more inclined to take an active role when he considered it to be absolutely essential. In this case he does pay a visit to the Motor Show in order to confirm a very strong suspicion.

Mystery at Olympia contains most of the ingredients that John Rhode fans tend to enjoy - exotic murder methods, some fun with alibis, questions about wills, some esoteric forensic science and an enthusiasm for technology (the author was clearly a bit of a motoring buff). Dr Priestley is his usual mercilessly unsentimental self (with a characteristic touch of ruthlessness at the end). Whether the book stretches credibility a bit too far in one key element is up to the reader to decide.

On the whole I highly recommend this one. And it’s readily available in an affordable brand new paperback edition!

Friday, June 1, 2018

Agatha Christie’s Evil Under the Sun

Given that I’ve just picked up a copy of Evil Under the Sun and I also have the relevant episode of the Poirot TV series I thought I’d try doing a back-to-back review of the novel and the TV version.

Evil Under the Sun was published in 1941 and it’s one of Agatha Christie’s most admired mysteries.

It has a classic setup. The Jolly Roger Hotel is located on an island (Smugglers’ Island) just off the Devon coast. It is connected to the mainland by a causeway. The island is a private island, only accessible to hotel guests. It would certainly not be impossible for someone to gain unauthorised access to the island, in fact it would not even be particularly difficult, but it would be just difficult enough to make it exceedingly unlikely that the murderer could have been a random passing stranger. More importantly it would not be easy for an outsider to reach the island without being seen. It therefore fulfils the main purpose of a golden age mystery setting - it means that the killer must be a guest at the hotel.

For murder has indeed been committed on Smugglers’ Island. The almost unanimous view of the guests is that the victim is the sort of woman who was extremely likely to get herself murdered, and that despite possessing fame and wealth she is not exactly going to be a great loss to the world.

Whatever her personal failings may have been murder is still murder, and Hercule Poirot takes murder very seriously. Poor Poirot should have known better - if you’re a famous detective and you decide to take a holiday you can be almost certain that your chosen holiday spot will also be chosen as a venue for a murder.

In this instance at least the murder does not take Poirot by surprise. He had more than half expected it. The situation surrounding the woman in question seemed to be tending inevitably towards some kind of disaster.

There’s no shortage of suspects and there are several perfectly plausible motives. Most of the suspects have alibis but if you’ve read plenty of detective fiction you’ll notice that the alibis are extremely complex, which is always a bit suspicious.

As I said earlier this is a book with a glowing reputation and at this point I’m going to confess to heresy. I was not overly impressed by this book.

With a golden age detective story you’re prepared to accept far-fetched and incredibly complicated and contrived solutions. The fact that they’re far-fetched and incredibly complicated and contrived can even be seen as a bonus, as long as three conditions are fulfilled. Firstly, once the solution is revealed your response should be that it’s outrageous but of course that’s how it must have happened. Nothing else would really make sense. In this case my reaction was that the solution did not ring true at all. It was simply ludicrous. It relied too much on luck and on the reactions of other people fitting in neatly with the plan. Not even the craziest killer would adopt a plan which was so hopelessly over-complicated that it was clearly doomed to failure.

The second condition is psychological plausibility. You have to be convinced that the murderer might just possibly have been capable of murder. In this case I felt that Christie cheated just a little in the way she presented several key characters to the reader. I didn’t believe their motivations at all.

The third condition is that the reader has to believe that based on the evidence available to him the detective could really have solved the case. In this instance I felt that Poirot pulled a rabbit out of a hat. There are some huge intuitive leaps. OK, Poirot is always inclined to make intuitive leaps but in this book the leaps seem more outrageous than usual.

This is typical Christie in many ways. It’s a spectacular display of plotting pyrotechnics. There is some very clever stuff with alibis. It’s all very ingenious. It’s just that the pyrotechnics are over-complicated and inherently unstable. The danger is that when the pyrotechnics are detonated the whole plot is likely to explode in mid-air. Which, in my view, is what happens.

I know it’s supposed to be one of her masterpieces but I’m afraid I’m not entirely convinced. Evil Under the Sun just did not quite work for me.

The TV Adaptation

The television adaptation in the Agatha Christie's Poirot series went to air in July 2003.

It is reasonably faithful to the book. The changes are mostly fairly unimportant. Captain Hastings and Miss Lemon are added to the story, which is no problem. Hastings is always useful - he provides Poirot with someone with whom to discuss important plot points. The local Chief Constable featured in the book is replaced in the TV version by Chief Inspector Japp, which again is no problem. In a TV series it’s obviously very advantageous to keep the same recurring characters.

The only significant change is that one character who is female in the book becomes male in the TV episode. I can see why they thought this change strengthened the plot although in my opinion it actually weakens it slightly.

The problems I had with the TV version were pretty much the same ones I had with the novel. The plot elements that seemed unconvincing on the printed page still seemed unconvincing on the TV screen.

The hotel of the novel becomes a sort of health farm in the TV adaptation which adds a few comic touches as Poirot copes very badly with being put on a healthy dietary and exercise regimen.

As always in this series the visuals are magnificent. The Burgh Island Hotel in Devon stands in for the Jolly Roger Hotel on Smugglers’ Island and it’s a wonderful location. The tractor ferry is a lovely touch.

If you enjoyed the novel more than I did (and almost everybody seems to fall into that category) then it’s quite likely you’ll like the TV version more than I did as well. There's nothing wrong with it as an adaptation, unless you're eccentric enough to share my doubts about the plotting.

Evil Under the Sun was published in 1941 and it’s one of Agatha Christie’s most admired mysteries.

It has a classic setup. The Jolly Roger Hotel is located on an island (Smugglers’ Island) just off the Devon coast. It is connected to the mainland by a causeway. The island is a private island, only accessible to hotel guests. It would certainly not be impossible for someone to gain unauthorised access to the island, in fact it would not even be particularly difficult, but it would be just difficult enough to make it exceedingly unlikely that the murderer could have been a random passing stranger. More importantly it would not be easy for an outsider to reach the island without being seen. It therefore fulfils the main purpose of a golden age mystery setting - it means that the killer must be a guest at the hotel.

For murder has indeed been committed on Smugglers’ Island. The almost unanimous view of the guests is that the victim is the sort of woman who was extremely likely to get herself murdered, and that despite possessing fame and wealth she is not exactly going to be a great loss to the world.

Whatever her personal failings may have been murder is still murder, and Hercule Poirot takes murder very seriously. Poor Poirot should have known better - if you’re a famous detective and you decide to take a holiday you can be almost certain that your chosen holiday spot will also be chosen as a venue for a murder.

In this instance at least the murder does not take Poirot by surprise. He had more than half expected it. The situation surrounding the woman in question seemed to be tending inevitably towards some kind of disaster.

There’s no shortage of suspects and there are several perfectly plausible motives. Most of the suspects have alibis but if you’ve read plenty of detective fiction you’ll notice that the alibis are extremely complex, which is always a bit suspicious.

As I said earlier this is a book with a glowing reputation and at this point I’m going to confess to heresy. I was not overly impressed by this book.

With a golden age detective story you’re prepared to accept far-fetched and incredibly complicated and contrived solutions. The fact that they’re far-fetched and incredibly complicated and contrived can even be seen as a bonus, as long as three conditions are fulfilled. Firstly, once the solution is revealed your response should be that it’s outrageous but of course that’s how it must have happened. Nothing else would really make sense. In this case my reaction was that the solution did not ring true at all. It was simply ludicrous. It relied too much on luck and on the reactions of other people fitting in neatly with the plan. Not even the craziest killer would adopt a plan which was so hopelessly over-complicated that it was clearly doomed to failure.

The second condition is psychological plausibility. You have to be convinced that the murderer might just possibly have been capable of murder. In this case I felt that Christie cheated just a little in the way she presented several key characters to the reader. I didn’t believe their motivations at all.

The third condition is that the reader has to believe that based on the evidence available to him the detective could really have solved the case. In this instance I felt that Poirot pulled a rabbit out of a hat. There are some huge intuitive leaps. OK, Poirot is always inclined to make intuitive leaps but in this book the leaps seem more outrageous than usual.

This is typical Christie in many ways. It’s a spectacular display of plotting pyrotechnics. There is some very clever stuff with alibis. It’s all very ingenious. It’s just that the pyrotechnics are over-complicated and inherently unstable. The danger is that when the pyrotechnics are detonated the whole plot is likely to explode in mid-air. Which, in my view, is what happens.

I know it’s supposed to be one of her masterpieces but I’m afraid I’m not entirely convinced. Evil Under the Sun just did not quite work for me.

The television adaptation in the Agatha Christie's Poirot series went to air in July 2003.

It is reasonably faithful to the book. The changes are mostly fairly unimportant. Captain Hastings and Miss Lemon are added to the story, which is no problem. Hastings is always useful - he provides Poirot with someone with whom to discuss important plot points. The local Chief Constable featured in the book is replaced in the TV version by Chief Inspector Japp, which again is no problem. In a TV series it’s obviously very advantageous to keep the same recurring characters.

The only significant change is that one character who is female in the book becomes male in the TV episode. I can see why they thought this change strengthened the plot although in my opinion it actually weakens it slightly.

The problems I had with the TV version were pretty much the same ones I had with the novel. The plot elements that seemed unconvincing on the printed page still seemed unconvincing on the TV screen.

The hotel of the novel becomes a sort of health farm in the TV adaptation which adds a few comic touches as Poirot copes very badly with being put on a healthy dietary and exercise regimen.

As always in this series the visuals are magnificent. The Burgh Island Hotel in Devon stands in for the Jolly Roger Hotel on Smugglers’ Island and it’s a wonderful location. The tractor ferry is a lovely touch.

If you enjoyed the novel more than I did (and almost everybody seems to fall into that category) then it’s quite likely you’ll like the TV version more than I did as well. There's nothing wrong with it as an adaptation, unless you're eccentric enough to share my doubts about the plotting.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)