Joe Hooper runs a fleabag motel in Creston, Oklahoma and he’s a loser who clings to the idea that one day he’ll be a winner. He knows that you don’t need talent or hard work to succeed. You just have to wait for that once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to come along and have the guts to grab it. When that happens for Joe he’s going to have real money and he’s going to get the hell out of Creston, Oklahoma.

That opportunity seems to have arrived when the Sheldons rent Cabin Number 2. Joe knows there’s something odd about them because Karl Sheldon is driving a new Buick. No-one who can afford a new car would stay in a dump like Joe’s motel. Sheldon also has an obviously phoney story about car trouble.

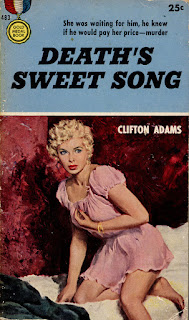

What really catches Joe’s attention is Sheldon’s wife Paula. She’s a gorgeous blonde. Joe wants a woman like that almost as much as he wants money. Maybe more.

Joe’s lucky break comes when he overhears a conversation in the Sheldons’ cabin. They are planning a payroll robbery. They’re going to rob the Provo Box company, Creston’s biggest employer. The payroll has to amount to at least thirty grand.

Joe doesn’t have any real criminal intentions until he has sex with Paula Sheldon. Then a plan starts to take shape in his mind. He’s going to force Karl Sheldon to cut him in on the robbery. After that Joe figures that somehow or other he and Paula will find a way to leave Karl out in the cold and they’ll go off together. Paula has already told him that she doesn’t love her husband. Joe will have everything he has ever wanted.

Joe is cunning but his grasp on reality is a bit tenuous. He should have realised right at the start that this blonde was going to be trouble. There were plenty of warning signs. It was obvious that there were things she wasn’t telling him about herself and about Karl. But Joe is so obsessed by Paula that he misses every single one of those warning signs.

The robbery is an attractive proposition. It will be a pushover. Of course in the world of noir fiction robberies that seem too easy never quite turn out that way. This time there’s a slight hitch, which means there’s a body to dispose of. Another hitch happens later.

Joe still thinks that everything will be OK and soon he’ll have Paula Sheldon.

Joe Hooper is the kind of guy who relies a lot on wishful thinking and he doesn’t think things through. And with Paula’s willing body to think about it he really isn’t thinking about anything else. He’s one of those guys who isn’t really evil but he’s weak and he’s greedy and he’s a sucker for glamorous blondes.

Paula is a classic femme fatale and poor Joe just can’t see that she’s a woman who uses sex ruthlessly to get what she wants. There’s also a slightly more complicated side to her. She isn’t completely rotten and corrupt. Things might have been easier had that been that case. She has more complex motivations which Joe just can’t fathom.

This is rural noir, with typical noir passions running amok in a small town. Small towns in which everybody knows everybody else can turn into nightmare noir worlds just as easily as the mean streets of the meanest big city. The desperation of dead-end life in a dead-end town is palpable.

The violence is very low-key. There’s lots of sexual tension and there’s lots of paranoid atmosphere and desperation.

It’s a classic noir plot but it’s nicely constructed and the very effective very noir ending hinges on something that Joe could never have anticipated.

The relationship between Joe and Paula is full of deceptions and contradictions. Joe can’t figure out if he loves her or hates her. Joe is a mess. His feelings about almost everything are confused. All three main characters are a bit more than just noir fiction stereotypes. They’re complicated people who don’t always fully understand why they do the things they do.

This is a fine noir novel and it’s highly recommended.

The Stark House Noir paperback edition also includes Adams’ first noir novel, Whom Gods Destroy.

.jpg)