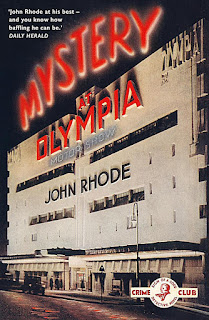

Mystery at Olympia (AKA Murder at the Motor Show) is a 1935 Dr Priestley mystery written by Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1964) under the name John Rhode.

At the Olympia Motor Show, in an immense crowd gathered around Stand 1001 to see the new and revolutionary touring car from the Comet Motor Company, an elderly man collapses and dies. This happens more or less right in front of Dr Priestley’s old friend Dr Oldland, whose efforts to save the man are unavailing. The elderly man is Nahum Pershore, a rather wealthy speculative builder.

At almost the same moment a pretty young parlourmaid in Mr Pershore’s household is taken violently ill. A Dr Formby is called in and he immediately suspects arsenic poisoning.

The post mortem on Mr Pershore raises more questions than it answers. Some very odd things have clearly been going on at the Pershore residence and it’s obvious that someone didn’t like Nahum Pershore. What is not obvious is whether he was murdered or not, and if so how.

In a John Rhode mystery you expect some cleverness when it comes to the method of despatching the murder victim or victims. In this book the author plays a number of different games with murder methods.

You also expect that science will play some part in the crime and in the solution. And in this instance there are some esoteric matters of forensic medicine involved.

This is also arguably an impossible crime story. There’s a man who is dead but he has no right to be. And what was a man who had zero interest in cars doing at a motor show?

As to the solution, there is perhaps a slight plausibility problem.

As usual it’s Superintendent Hanslet who does most of the investigating. He’s the principal detective character with Dr Priestley remaining in the background. And as usual Hanslet is wrong on just about every point. He has a great enthusiasm for constructing elaborate theories and a lack of evidence to support those theories is something he really doesn’t worry about. Priestley’s interpretations of the evidence are of course very much sounder. And while Dr Priestley appears to be taking no active part in the investigation this is not quite the case. He is constantly feeding Hanslet hints that, with luck, will eventually put the superintendent on the right track.

Hanslet is dogged and he’s thorough but I have to say that I would be very very worried if I happened to be an innocent person who was a suspect in one of his investigations. Superintendent Hanslet’s powers of imagination are impressive but his powers of detection leave quite a lot to be desired.

It became increasingly rare for Priestley to go out into the field so to speak. He came to prefer sitting in comfort in his own home whilst pulling the strings of the police investigation. In his 1930s mysteries he was more inclined to take an active role when he considered it to be absolutely essential. In this case he does pay a visit to the Motor Show in order to confirm a very strong suspicion.

Mystery at Olympia contains most of the ingredients that John Rhode fans tend to enjoy - exotic murder methods, some fun with alibis, questions about wills, some esoteric forensic science and an enthusiasm for technology (the author was clearly a bit of a motoring buff). Dr Priestley is his usual mercilessly unsentimental self (with a characteristic touch of ruthlessness at the end). Whether the book stretches credibility a bit too far in one key element is up to the reader to decide.

On the whole I highly recommend this one. And it’s readily available in an affordable brand new paperback edition!

pulp novels, trash fiction, detective stories, adventure tales, spy fiction, etc from the 19th century up to the 1970s

Showing posts with label john rhode. Show all posts

Showing posts with label john rhode. Show all posts

Friday, June 8, 2018

Wednesday, February 28, 2018

John Rhode's Death at Breakfast

Death at Breakfast is 1936 Dr Priestley mystery written by Cecil John Street under his John Rhode pseudonym.

Victor Harleston is a clerk working for an accounting firm. He lives with his half-sister Janet who keeps house for him. On one particular fateful day she brings him his morning up of tea as usual. Half an hour later he sits down to breakfast but seems somewhat unwell. He gets up from the table, stumbles, then collapses. Janet hurries to the nearby surgery of Dr Oldland. By the time the doctor arrives it is clear with Victor is beyond human aid. He dies shortly afterwards. It is also clear to Dr Oldland that Victor has died due to the effects of poison.

Victor was not the most pleasant of men. In fact he was exceedingly unpleasant and remarkably mean about money. Janet is obviously not overly distressed by his death. Janet was the only other person in the house and it soon transpires that she had a very strong motive for murder. To Superintendent Hanslet it seems like a very clear-cut case indeed.

The postmortem however creates difficulties. It’s not consistent with the evidence found at the crime scene.

It’s also odd that Hanslet’s old friend Dr Priestley seems to be interested in the case - usually Hanslet has a great deal of trouble persuading Priestley to become involved.

In the course of their investigation Superintendent Hanslet and Inspector Waghorn of the Yard uncover evidence of a second murder. There is obviously absolutely no connection between the two crimes. Well, there is one odd link but Hanslet and Waghorn aren’t too concerned. It’s clearly just a coincidence. Dr Priestley however takes a very dim view of coincidences.

As usual Dr Priestley does not find it necessary to leave his comfortable home in Westbourne Terrace in order to visit crime scenes and crawl about on hands and knees looking for cigar ash. He sits in his armchair and gives the case his full intellectual attention. He offers suggestions, which are invariably unexpected but invariably useful. His main contributions however are his penetrating criticisms of the theories that Hanslet and Waghorn construct in order to explain the link between the two crimes. The problem is that these theories do not explain the link at alland and rely on motives which are entirely fanciful, although Hanslet is not always pleased to have these things pointed out to him.

Superintendent Hanslet does not exactly cover himself with glory in this case. His theorising is enthusiastic and imaginative but based on little more than guesswork and wishful thinking. Priestley is as always dispassionate and coolly logical and prefers to wait for actual evidence to accumulate before committing himself to an attempted solution.

On the other hand it has to be admitted that both Hanslet and Waghorn are dogged and thorough and once pointed in the right direction they can be relied upon to find any evidence that is capable of being found.

Rhode is sometimes regarded as a writer more concerned about the how than the who when it comes to mysteries. For those who enjoy that approach this book features an extremely clever and original murder method. But those more interested in whodunits should not be disappointed.

Those with a passion for the history of forensic science will be interested in the material about blood and bloodstains, subjects that were only just beginning to be understood in 1936.

This is golden age detective fiction at its purest. No romance sub-plots, no time wasted on characterisation, just an intricate plot that works like clockwork and a remorselessly logical detective (although despite his devotion to logic I personally find Priestley to be quite entertaining as a character). Death at Breakfast achieves exactly what it sets out to achieve. Highly recommended.

Victor Harleston is a clerk working for an accounting firm. He lives with his half-sister Janet who keeps house for him. On one particular fateful day she brings him his morning up of tea as usual. Half an hour later he sits down to breakfast but seems somewhat unwell. He gets up from the table, stumbles, then collapses. Janet hurries to the nearby surgery of Dr Oldland. By the time the doctor arrives it is clear with Victor is beyond human aid. He dies shortly afterwards. It is also clear to Dr Oldland that Victor has died due to the effects of poison.

Victor was not the most pleasant of men. In fact he was exceedingly unpleasant and remarkably mean about money. Janet is obviously not overly distressed by his death. Janet was the only other person in the house and it soon transpires that she had a very strong motive for murder. To Superintendent Hanslet it seems like a very clear-cut case indeed.

The postmortem however creates difficulties. It’s not consistent with the evidence found at the crime scene.

It’s also odd that Hanslet’s old friend Dr Priestley seems to be interested in the case - usually Hanslet has a great deal of trouble persuading Priestley to become involved.

In the course of their investigation Superintendent Hanslet and Inspector Waghorn of the Yard uncover evidence of a second murder. There is obviously absolutely no connection between the two crimes. Well, there is one odd link but Hanslet and Waghorn aren’t too concerned. It’s clearly just a coincidence. Dr Priestley however takes a very dim view of coincidences.

As usual Dr Priestley does not find it necessary to leave his comfortable home in Westbourne Terrace in order to visit crime scenes and crawl about on hands and knees looking for cigar ash. He sits in his armchair and gives the case his full intellectual attention. He offers suggestions, which are invariably unexpected but invariably useful. His main contributions however are his penetrating criticisms of the theories that Hanslet and Waghorn construct in order to explain the link between the two crimes. The problem is that these theories do not explain the link at alland and rely on motives which are entirely fanciful, although Hanslet is not always pleased to have these things pointed out to him.

Superintendent Hanslet does not exactly cover himself with glory in this case. His theorising is enthusiastic and imaginative but based on little more than guesswork and wishful thinking. Priestley is as always dispassionate and coolly logical and prefers to wait for actual evidence to accumulate before committing himself to an attempted solution.

On the other hand it has to be admitted that both Hanslet and Waghorn are dogged and thorough and once pointed in the right direction they can be relied upon to find any evidence that is capable of being found.

Rhode is sometimes regarded as a writer more concerned about the how than the who when it comes to mysteries. For those who enjoy that approach this book features an extremely clever and original murder method. But those more interested in whodunits should not be disappointed.

Those with a passion for the history of forensic science will be interested in the material about blood and bloodstains, subjects that were only just beginning to be understood in 1936.

This is golden age detective fiction at its purest. No romance sub-plots, no time wasted on characterisation, just an intricate plot that works like clockwork and a remorselessly logical detective (although despite his devotion to logic I personally find Priestley to be quite entertaining as a character). Death at Breakfast achieves exactly what it sets out to achieve. Highly recommended.

Thursday, May 12, 2016

John Rhode's Dead Men at the Folly

Dead Men at the Folly was the thirteenth Dr Priestley mystery written by Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1964) under the pen-name John Rhode. It was originally published in 1932.

Street was a popular writer in his day but his work has languished in obscurity since his death. Or at least this was the case until quite recently. in the past few years the detective fiction of the so-called golden age has been experiencing a major revival in popularity. And with the reprinting by the British Library of a couple of the detective novels he wrote under the name Miles Burton the work of Street is now beginning to attract considerable interest. In fact at the present moment just about every vintage crime blogger seems to be blogging about Street’s books. The excellent Beneath the Stains of Time blog has for example just featured an excellent review of the Miles Burton novel Death in the Tunnel.

Having only read one of the Miles Burtons I can’t comment too much on them although Death at Low Tide was certainly very good indeed.

On the other hand I’ve read quite a few of the Dr Priestley mysteries and I count myself as an enthusiastic fan.

Dead Men at the Folly opens with a motorcyclist lost in the countryside. He notices a very striking structure at the top of a ridge not too far off the road and feels compelled to investigate it. The structure is Tilling’s Folly, a tall circular tower topped with an observation gallery. On the ground at the base of the tower the motorcyclist makes a gruesome discovery - the dead body of a man.

Inspector Richings of the local constabulary at Charlton Montague is soon on the scene. It seems to be a fairly obvious case of suicide but Richings is a careful and thorough policeman. He is not inclined to overlook the small details and those small details cause him some concern. He suspects foul play. Fortunately the Chief Constable is a sensible fellow as well and both men realise that this has the potential to be a difficult case. Furthermore they can make no progress in identifying the dead man, which strongly suggests this might not be a purely local matter. The prudent thing to do would be to ask Scotland Yard for assistance and the sooner the better. As the discovery of the body took place on the Saturday before Christmas Day Superintendent Hanslet of Scotland Yard finds he has no-one available to assign to the case. He therefore decides to take on the case himself.

Hanslet doesn’t take long to realise that Richings’ suspicions were well-founded. This is murder.

Initially the case seems likely to be frustrating and time-consuming. No progress has been made in identifying the body. And then, as often happens, all the pieces start to slot neatly into place. It was all very straightforward after all. Within just a few days Superintendent Hanslet has solved the case. He is so pleased with himself that he can’t wait to tell his old friend Dr Priestley. Oddly enough the irascible but brilliant scientist and part-time criminologist doesn’t seem overly impressed by Hanslet’s solution, and Priestley is tactless enough to point out what appear to him to be some very major flaws in an otherwise satisfactory solution. Hanslet however is so convinced of the essential soundness of his own theory that he dismisses such annoying nit-picking. Dr Priestley is a fine fellow and a good friend and unquestionably brilliant but he is often inclined to cast quite unnecessary doubts on Superintendent Hanslet’s theories.

Hanslet returns to Charlton Montague full of confidence that he is just about to wrap the case up when a discovery is made that reveals that his wonderfully impressive theory is in fact a house of cards and, as houses of cards are wont to do, is about to collapse in an untidy heap. It appears Hanslet is going to need Dr Priestley’s help after all.

Dr Priestley does not make his first entry until quite late in the game and he remains very much in the background. He’s such a memorable character that he still somehow manages to dominate the story and there’s perhaps something to be said for keeping him in reserve so that the reader anxiously awaits his appearance knowing that his arrival will kick the plot into high gear.

Rhode’s plotting is strong, as always. While Rhode has often been dismissed as a dull writer I found the setting to be quite vividly rendered. The Folly itself is a perfect setting for murder. Rhode tended to avoid country house settings and the characters for the most part are drawn from the middle class or have even slightly more humble backgrounds. The book gives us quite an entertaining glimpse of a vanished but very everyday reality.

A fine entry in the Dr Priestley series, highly recommended.

Tuesday, May 3, 2016

Miles Burton's Death at Low Tide

Major Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1964) was one of the most prolific of British golden age detective fiction authors. As well as seventy-odd Dr Priestley mysteries published as John Rhode he produced more than sixty mysteries under the pseudonym Miles Burton. The Miles Burton books featured amateur sleuth Desmond Merrion, usually working alongside his friend Inspector Arnold of Scotland Yard. Death at Low Tide appeared in 1938.

Captain Stanlake is Harbour Master at Brenthithe, a sleepy little port in the West Country. Stanlake is a man with vision but he is not a popular man. He has plans to transform Brenthithe into a bustling commercial port. This would be of great benefit to some of the town’s inhabitants, but not to all of them. Brenthithe is effectively two towns. The Old Town relies on fishing and on Brenthithe’s rapidly declining status as a port. The New Town depends on tourism. Stanlake’s plans would benefit the Old Town but would involve draining Bollard Bay, which would effectively destroy the tourist trade (Bollard Bay being a paradise for small boats).

All of this might seem irrelevant but it is in fact crucial to the plot. Stanlake’s plans have aroused a great deal of opposition and there are many townsfolk who would be overjoyed were he to fall off the pier one fine day and drown. And one day he does fall off the pier. But he does not drown. He is dead before he hits the water, with a bullet hole neatly placed between the eyes.

The Chief Constable realises immediately that he is going to need the assistance of the Yard, and that assistance soon arrives in the person of Inspector Arnold. The case might well beyond that fine officer as well and Arnold is rather relieved when his old friend Desmond Merrion turns up.

The case is baffling indeed. Stanlake was alone on the pier when he was shot. He could not have been shot from a boat - the angle at which the bullet struck the victim’s head precludes that possibility. Since he was entirely alone on the pier the obvious conclusion is that he shot himself. Not one person in Brenthithe believes that Stanlake killed himself. Inspector Arnold and Desmond Merrion do not believe it either. It was murder, but an impossible murder.

Equally baffling is the fatal bullet. Scotland Yard’s ballistics expert has never seen such a bullet. It was clearly home-made, and fired from no known make of gun.

Suspects there are in abundance. Hundreds of people had reason to want Stanlake dead. The trouble is, not one person in Brenthithe could have killed him. No-one could have killed him, but someone did.

Street was always fairly sound when it came to plotting and this novel is no exception. The murder method is delightfully ingenious. The trick with impossible crime stories is to make said impossible crime suitably unusual and baffling whilst still making the solution plausible. The trick is pulled off here with considerable success. Street loved clever plots involving guns, perhaps not surprisingly in view of his service as an artillery officer in the First World War. Street had later transferred from the artillery to intelligence. It’s hard to think of a more perfect background for someone who would turn to the writing of detective fiction - an insider’s knowledge of both ballistics and the art of deception!

In Dr Priestley Street had created a reasonably colourful fictional detective - opinionated, eccentric and cantankerous. Desmond Merrion by comparison seems a little on the bland side. Street was more interested in plotting than in characterisation in any case but in this novel he does create one memorable character - the town of Brenthithe itself. It is a town divided against itself. It is also a town caught between the past and the future. It’s rather like England, a country already in decline caught between an industrial past and an uncertain future that might bring prosperity to some but ruin to others. All very prescient for a novel written in 1938. Street shows sympathy for both sides in the divided town. Stanlake was a very abrasive man but in his own way he believed he had the best interests of the town at heart. Like most visionaries his vision had some huge blind spots in it. Whatever his faults he did not deserve to be murdered, but on the other hand it’s hardly surprising that those whose livelihoods were threatened by his plans should have considered him to be a deadly enemy.

I can’t help thinking that this novel would have been even more fun as a Dr Priestley mystery. As it stands Death at Low Tide is still a fine example of the detective fiction of the 30s. Highly recommended.

Thursday, April 9, 2015

John Rhode's The Davidson Case

The Davidson Case, published in 1929, was one of the early Dr Priestley detective novels written by Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1964) under the pen-name John Rhode. It illustrates some of the author’s great strengths as a mystery writer while also suffering from some fairly serious weaknesses.

John Rhode was one of the authors contemptuously dismissed by critic Julian Symons as belonging to the Humdrum School of detective fiction. My own view is that Symons was quite wrong about these writers in general and very wrong about Rhode in particular. I’ve found the Dr Priestley mysteries to be anything but humdrum. The Davidson Case is not however one of his better efforts.

Sir Hector Davidson is the head of a chemical engineering firm. The firm was built up by his father and grandfather but Sir Hector is running the company into the ground. He cares about nothing other than extracting as much money from the company as possible in order to finance his dissolute lifestyle. His cousin Guy Davidson has been watching Sir Hector’s activities with despondency for several years. Guy really does care about the company and about its employees. He is a research chemist himself and has a genuine passion for the subject.

When Sir Hector is found dead no-one is very upset. In fact there is a general sense of relief. His cousin Guy Davidson, who now succeeds to the baronetcy and who will now control the firm’s fortunes, is as relieved as anyone.

The circumstances of Sir Hector’s death are peculiar. He had been returning to his country house. On arrival at the railway station he had been surprised that his servant was not waiting for him with the car. He engaged the services of a local carrier to transport him in his van to his home. He was found dead in the back of the van, stabbed to death by a rather curious improvised stiletto.

It is not an impossible crime but finding a theory that will adequately account for the circumstances is a challenge even for Dr Priestley. The local police are baffled. When Chief Inspector Hanslet of Scotland Yard is called in he can make little progress either until Dr Priestley puts forward a theory that seems watertight. Or is it?

The murder method is certainly ingenious. It’s exceptionally complex but it is worked out in intricate detail and it hangs together remarkably well.

The problem lies in the solution. There are a couple of factors in this case that are just a bit too obvious. Rhode is careful to provide most of the clues necessary for the solution but the alert reader is almost certain to spot the main points of this solution. It also has to be said that the story relies a little too heavily on the police failing to follow up certain very obvious lines of inquiry, and in order to keep the issue in doubt the author perhaps is guilty of holding back some important information until rather late in the day. Once this information is revealed the solution is straightforward. Rhode was usually very skillful in his plotting but on this occasion he was obviously aware that had he not held back this information the explanation of the crime would have been all too obvious.

One interesting feature of Dr Priestley as a detective is that his only interest in crime is the purely intellectual interest it provides. If he is able to solve the crime to his own satisfaction he is perfectly content. Whether the criminal is brought to justice is of no concern to him. The Davidson Case provides an example of this approach that is slightly startling for a novel published in 1929. A Hercule Poirot would certainly not have approved of Dr Priestley’s indifference to the matter of seeing that justice is done.

If you have not sampled any of John Rhode’s Dr Priestley mysteries then I strongly urge you to do so but The Davidson Case is definitely a lesser effort. The Venner Crime, The Claverton Mystery and The Motor Rally Mystery are on the other hand quite superb examples of golden age detective fiction while Dr. Priestley Investigates is rather outrageous fun.

Thursday, November 27, 2014

John Rhode’s The Claverton Mystery

John Rhode’s The Claverton Mystery (published in the US as The Claverton Affair) appeared in 1933. It was the fifteenth of the seventy-two Dr Priestley mysteries written by Major Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1965) using the John Rhode pseudonym.

It had been preceded by the very entertaining The Motor Rally Mystery (US title Dr Priestley Lays a Trap) and was followed by the excellent The Venner Crime. Several of the characters in The Claverton Mystery also appear in The Venner Crime.

The Claverton Mystery begins with a visit by Dr Priestley to an old friend, Sir John Claverton, who has fallen ill. They had once been close but since the war they had drifted apart somewhat. An urgent message from Claverton suggested that perhaps all was not well with him and Priestley, feeling slightly guilty for not having made more effort to keep up the friendship, arrives at Claverton’s rather gloomy dwelling. The truth is that Claverton has become just a little eccentric, insisting on remaining at 13 Beaumaris Place even though the neighbourhood has lost much of its former charm. Claverton had, rather unexpectedly, inherited the house and a large fortune some years earlier and he appears to have developed a rather superstitious attachment to the place.

As soon as Priestley arrives it is clear to him that something is not quite right. Claverton has always lived alone so who are these strange people who seem to have taken up residence there? Why is Claverton now reluctant to tell Priestley why he summoned him? And if Claverton’s illness is really not serious (and Dr Oldland assures him that this is the case) why is the doctor clearly much more concerned than a minor illness would warrant?

Claverton’s death deepens the mystery considerably, the post-mortem results coming as a considerable shock to Priestley. Claverton died from natural causes although Priestley is convinced otherwise.

Of course there is a will, which deepens the mystery still further. And Claverton’s relatives give Priestley a very uneasy feeling.

Priestley dislikes forming theories until he feels he has all the facts at his command. If the accumulation of these facts happens to take several months that is no problem - he is a patient man and he is prepared to wait.

Dr Priestley is generally speaking the type of amateur detective who regards his hobby as a stimulating exercise in puzzle-solving, a very satisfying pastime but one that engages the intellect rather than the emotions. This case is quite different. Priestley was genuinely fond of Claverton and his old friend’s death upset him a good deal. The truth is that Priestley is by no means as emotionally cold as his crusty exterior would suggest.

Another respect in which this novel differs from most of the John Rhode mysteries is in the decidedly gothic atmosphere and the hints of the occult. The author does not overdo these elements but they are certainly present.

This novel contains all the features that modern critics tend to disparage in golden age detective fiction. The motive hinges on the provisions of a will and an unbreakable alibi forms an important plot point. The murder method is somewhat unlikely if undeniably ingenious. Events in the distant past play a major rôle. Rhode was an author with no interest in “subverting” the conventions of his chosen genre. While this will not endear him to the postmodernists I personally admire his approach. Telling a good story while remaining strictly within the confines of genre conventions and finding a way to make that story still seem fresh and interesting is something which in my view requires more talent than “subverting” or “transcending” those conventions. And Rhode was a very good story-teller indeed.

The solution to the puzzle involves one element that might seem to be pulled out of a hat but in fact Rhode has been scrupulously fair in providing clues to alert us to the existence of that particular metaphorical hat.

The Claverton Mystery is golden age detective fiction at its best. Immensely enjoyable and highly recommended.

Wednesday, July 16, 2014

John Rhode’s The Motor Rally Mystery

|

Major Cecil John Charles Street

|

Major Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1964) was the author of around 140 detective novels, including more than 70 published under the pseudonym John Rhode and featuring his best-known detective, Dr Priestley. The Motor Rally Mystery, which appeared in 1933, was the fourteenth of the Dr Priestley mysteries. It was published in the US as Dr Priestley Lays a Trap.

The Motor Rally Mystery differs in several ways from the conventional golden age detective tale. It is not strictly speaking a fair-play puzzle-plot mystery. The main emphasis is on the unusual and very clever murder method, and on the brilliant and intricate manner in which Dr Priestley elucidates this method.

Three friends are taking part in a motor rally. Bob Weldon has entered his powerful Armstrong-Siddeley saloon in the rally and is confident it will give a good account of itself. His co-driver is a business associate, Richard Gateman. The third member of the team is a younger man, Harold Merefield, who task is to take care of navigation. Harold Merefield happens to be employed as a private secretary by Dr Launcelot Priestley, a circumstance that will become important. The three men are having a rather frustrating time of it, having been delayed for several hours by a fog and they will be struggling to reach the next control point within the allotted time. They are however not destined to reach that control point or to finish the rally. They see a Comet sports car that has run off the road into a ditch, apparently at high speed. This car is also competing in the rally. The three friends naturally stop to see if they can render any assistance and make a grim discovery. The driver of the Comet and his passenger are both dead.

They naturally notify the police at once. Their investigation is fairly brief. This was obviously a tragic accident, and at the inquest a verdict of accidental death is returned. The matter seems to be resolved, until a curious discovery is made. The driver of the Comet sports car was an Aubrey Lessingham, but the Comet sports car in which and his cousin and co-driver Tom Purvis were killed was not Aubrey Lessingham’s car. It was a car of identical make and of the same colour, but the chassis number and the engine number reveal that it is a different car. This odd circumstance leads Superintendent Hanslet to suspect that Lessingham had been involved in a car theft racket. At this point Hanslet’s old friend Dr Priestley takes an interest in the case. Dr Priestley comes to a most startling conclusion - there has certainly been a crime committed but the crime is not car theft, it is murder.

In order to solve this crime Dr Priestley will have to reconstruct an extraordinary and intricate sequence of events and the way in which he does so constitutes a tour-de-force on the part of the crusty scientist-detective, and an equally impressive tour-de-force on the part of the author.

Those who insist that their golden age detective yarns should conform to the rules of fair play will have some major issues with this book. In my view these issues have nothing to do with any lack of competence on the part of the author; he was simply not interested in writing a conventional puzzle-plot mystery although no-one familiar with his book could reasonably doubt that he was perfectly capable of writing very fine books of that type. In this instance he was trying something slightly different. On the basis of the few John Rhode books I’ve read so far I’d be inclined to say that the author liked to vary his approach at times, and on occasion to be slightly daring. I find it difficult to understand critics who have dismissed him as a dull writer. To me he seems anything but dull.

As in the other books in which he features Dr Priestley proves to be a very satisfying fictional sleuth. He is a scientist and he is at his happiest whenever he has discovered an embarrassing mistake in the work of a fellow scientist. If the mistake happens to be found in an extremely arcane and esoteric piece of research he is even happier. He takes a similar approach to the science of detection. Dr Priestley can be relied upon to express his disagreements with accepted theories in a trenchant and rather acidic manner. He is not perhaps a man to inspire instant affection but his penetrating intelligence and his refusal to take anything for granted make him an entertaining and stimulating companion.

In The Motor Rally Mystery his unwillingness to take even the most apparently obvious and clear-cut facts at face value is shown to particularly good effect.

Golden age detective fiction purists may take issue with this book but if you’re prepared to accept it on its own terms it’s delightful entertainment. Highly recommended.

Sunday, April 20, 2014

John Rhode’s The Venner Crime

|

| John Rhode (Major Cecil John Charles Street) |

The Venner Crime, published in 1933, was one of John Rhode’s many detective novels featuring the amateur scientific detective Dr Priestley. John Rhode was one of a number of pseudonyms used by prolific English crime novelist Major Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1965).

This is the third of the Dr Priestley novels that I’ve read so far and I’m finding them more and more to my taste.

The novel starts with a disappearance rather than a murder. In fact, though there are several sudden deaths it’s not until very near the end of the book that Dr Priestley can be certain that any actual murder has occurred. Even the disappearance does not initially seem all that sinister. The vanished man is a young man named Ernest Venner. He had told his secretary he’d be away for a few days and then later the same afternoon told his sister (with whom he lives) that he’d be back later that night. If he had intended to disappear why would he tell one person he’d be gone for some days and tell someone else he’d return that evening. It’s these tantalisingly minor discrepancies that arouse Dr Priestley’s interest.

The most suspicious circumstance is that Venner’s uncle, Denis Hinchliffe, had died suddenly under curious circumstances shortly before Venner’s vanishing act. Hinchliffe’s symptoms strongly suggested strychnine poisoning. Dr Priestley’s friend Dr Oldland was not satisfied the death was due to natural causes and refused a death certificate. A subsequent post-mortem carried out by the distinguished Home Office pathologist Sir Alured Faversham (also an old friend of Priestley’s) established beyond doubt that there was no trace of strychnine in the body and that death was due to tetanus.

Hinchliffe had been a very wealthy man and both Ernest Venner and his sister Christine were hoping to inherit his fortune, Hinchliffe having no other family. The hoped-for inheritance certainly provides a strong motive and Hinchliffe’s death was very fortunate indeed for Ernest Venner who was in very serious financial difficulties. But the post-mortem ruled out murder fairly conclusively.

There’s still the matter of Venner’s disappearance and when several weeks pass without any trace of the missing man the possibility that he has been murdered has to be considered. On the other hand a man might well wish to disappear if he has committed a serious crime, although in this case his uncle’s extraordinarily fortuitous death was due to natural causes.

A body is eventually discovered, but it is not the body of Ernest Venner. In fact it seems to have little connection with Venner’s disappearance, apart from a few details that could be explained by coincidence. Dr Priestley is inclined to believe that innocent coincidences are quite possible, but he is also aware that not all coincidences are so innocent.

Although he is less well remembered than some of his contemporaries John Rhode’s Dr Priestly detective novels were extremely popular in the 1920s and 1930s. Since only a handful were ever published in paperback surviving copies can be a little on the expensive side. Rhode was one of the author’s dismissed by critic Julian Symons as belong to the “humdrum” school of detective fiction. To some extent I can understand Symons’ reasoning, especially given his own preference for psychological crime novels. The Dr Priestley novels are very much of the puzzle-solving type and the atmosphere can be rather genteel (although Dr Priestley Investigates features quite outrageously extravagant plotting). Personally I’m inclined to regard those aspects of his writing that Symon disliked as features rather than bugs. While Dr Priestley can be a little of the gruff side these novels are essentially civilised intelligent entertainment. Those who prefer their crime fiction uncivilised are probably not going to enjoy them. And, sadly, crime fiction has become increasingly uncivilised since Rhode’s heyday.

I find Rhode’s style to be pleasing, with just enough dashes of erudition and sophistication.

Rhode can certainly not be accused of failing to play fair with his readers. His clues are all hidden in plain sight and the eventual solution to the mystery is eminently logical (Dr Priestley being a profoundly logical sort of fellow.

It should perhaps be noted that Dr Priestly is a scientist rather than a medical doctor. He’s rather in the style of R. Austin Freeman’s Dr Thorndyke, putting his trust in science and logic rather than intuition.

The Venner Crime is a fine example of the English golden age detective story at its best, with strong plotting and a detective hero with just enough inherent interest to avoid blandness but without being deliberately eccentric to the point where his eccentricities would overshadow the plot. A thoroughly enjoyable read. Highly recommended.

Friday, August 9, 2013

Dr. Priestley Investigates

Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1965) wrote no less than 140 books, most of them detective novels, under a variety of pseudonyms. This impressive output included dozens of Dr Priestley mysteries, all written under the name John Rhode. For the sake of convenience I will refer to the author by this name. Dr. Priestley Investigates (this is the US title of a book originally published in the UK as Pinehurst) was one of his earlier efforts, appearing in 1930.

This novel starts with an apparent crime that turns out to be very different from that suggested by initial appearances. A drunk driver is pulled up and in the dickey seat of his car is found a body with a rug draped over it. Superintendent King of the Lenhaven Police believes he has found a satisfactory explanation for this odd occurrence and the case appears to be closed. That is, until Dr Priestley takes a hand. A serious crime has certainly been committed but it is merely the culmination of a series of criminal acts stretching back over nearly a decade, crimes which even include piracy!

The ingredients are certainly there for a lively and engaging tale and that’s more or less what we get.

Rhode was one of the writers dismissed by critic Julian Symons as the Humdrum School. That’s a little unfair but it has to be admitted that Dr Priestley (in this novel at least) is a remarkably colourless detective. In fact the most interesting character in this tale is the dead man the discovery of whose body starts the initial investigation.

Rhode might be a little weak in the area of characterisation but he could certainly construct the kind of intricate plot that readers of that era demanded. The plot is both complex and colourful. Much of the action takes place in a very unusual setting - a beached yacht.

Dr Priestley relies more on purely intellectual deduction than on physical clues although there are a couple of such clues that do prove to be important. And Rhode is, when the occasion demands, prepared to have a detective crawl about on his hands and knees examining tyre prints (although in his case the procedure is carried out by a secondary investigator, Chief Inspector Hanslet).

Mention of Chief Inspector Hanslet brings up an interesting feature of the book. It does not quite follow the familiar pattern of having an amateur detective single-handedly solving the case while official police detectives flounder about uselessly. Both Superintendent King and Chief Inspector Hanslet play important roles in unravelling the mystery. In that respect the book combines features of the police procedural with the more common (at the time the book was published) amateur detective story. Rhode rather neatly manages to have the best of both worlds - his official police detectives have the advantage of being able to call on the vast resources of the police force while his unofficial detective has the advantages of freedom of action and time for purely intellectual reflection.

Rhode gives us rather more action that we would normally expect in this style of detective story. There are no less than three gun battles, not to mention piracy on the high seas. At times the reader could be forgiven for thinking that he’s picked up a thriller by mistake.

The only real flaw I can find in this tale is that the main detective, Dr Priestley, could have been made a bit more memorable and distinctive. It may well be that the author has deliberately made him somewhat on the bland side, a practice that was not uncommon at the time and represented a reaction against the Sherlock Holmes type of colourful and eccentric sleuth, a type that often ended up dominating the story at the expense of the plot (it’s worth remembering that the careers of Conan Doyle and John Rhode overlapped).

Dr. Priestley Investigates is an entertaining novel that demonstrates that the writers of the “Humdrum School” were often far from humdrum. Recommended.

This novel starts with an apparent crime that turns out to be very different from that suggested by initial appearances. A drunk driver is pulled up and in the dickey seat of his car is found a body with a rug draped over it. Superintendent King of the Lenhaven Police believes he has found a satisfactory explanation for this odd occurrence and the case appears to be closed. That is, until Dr Priestley takes a hand. A serious crime has certainly been committed but it is merely the culmination of a series of criminal acts stretching back over nearly a decade, crimes which even include piracy!

The ingredients are certainly there for a lively and engaging tale and that’s more or less what we get.

Rhode was one of the writers dismissed by critic Julian Symons as the Humdrum School. That’s a little unfair but it has to be admitted that Dr Priestley (in this novel at least) is a remarkably colourless detective. In fact the most interesting character in this tale is the dead man the discovery of whose body starts the initial investigation.

Rhode might be a little weak in the area of characterisation but he could certainly construct the kind of intricate plot that readers of that era demanded. The plot is both complex and colourful. Much of the action takes place in a very unusual setting - a beached yacht.

Dr Priestley relies more on purely intellectual deduction than on physical clues although there are a couple of such clues that do prove to be important. And Rhode is, when the occasion demands, prepared to have a detective crawl about on his hands and knees examining tyre prints (although in his case the procedure is carried out by a secondary investigator, Chief Inspector Hanslet).

Mention of Chief Inspector Hanslet brings up an interesting feature of the book. It does not quite follow the familiar pattern of having an amateur detective single-handedly solving the case while official police detectives flounder about uselessly. Both Superintendent King and Chief Inspector Hanslet play important roles in unravelling the mystery. In that respect the book combines features of the police procedural with the more common (at the time the book was published) amateur detective story. Rhode rather neatly manages to have the best of both worlds - his official police detectives have the advantage of being able to call on the vast resources of the police force while his unofficial detective has the advantages of freedom of action and time for purely intellectual reflection.

Rhode gives us rather more action that we would normally expect in this style of detective story. There are no less than three gun battles, not to mention piracy on the high seas. At times the reader could be forgiven for thinking that he’s picked up a thriller by mistake.

The only real flaw I can find in this tale is that the main detective, Dr Priestley, could have been made a bit more memorable and distinctive. It may well be that the author has deliberately made him somewhat on the bland side, a practice that was not uncommon at the time and represented a reaction against the Sherlock Holmes type of colourful and eccentric sleuth, a type that often ended up dominating the story at the expense of the plot (it’s worth remembering that the careers of Conan Doyle and John Rhode overlapped).

Dr. Priestley Investigates is an entertaining novel that demonstrates that the writers of the “Humdrum School” were often far from humdrum. Recommended.

Monday, October 1, 2012

The House on Tollard Ridge

Cecil John Charles Street (1884-1965) wrote detective novels under a variety of pseudonyms, including John Rhode. The House on Tollard Ridge was published under this name in 1929.

It was one of many books to feature Dr Priestley, although he does not appear in this book until quite late. Dr Priestley, like R. Austin Freeman’s Dr Thorndyke, was a scientific detective. Dr Priestley is a slightly eccentric maverick scientist who has discovered that solving crimes can be a pleasant intellectual diversion. He is not motivated by money, nor by any passionate belief in justice. A crime is merely a puzzle to be solved.

In this case the crime is murder. A Mr Barton is found dead, his skull crushed by a blunt instrument. Mr Barton had been living in seclusion in a house on Tollard Ridge, a house a few miles from the village of Charlton Abbas and accessible only on foot. The town of Lenhaven is about fourteen miles distant. Since the death of his beloved wife he had been living there alone until a Mr and Mrs Hapgood had prevailed upon him to move in with them at Tilford Farm.

Mr Barton had been a wealthy man but quite a generous one and was generally so well liked that no-one can conceive that anyone could have a motive for murdering him. Mrs Hapgood has always referred to Mr Barton as Uncle Sam and regarded him almost as a father although in fact they were not related by blood.

Superintendent King is soon on the scene. Slowly a solution to the crime suggests itself to him. A son who has been disowned by Mr Barton, a young man given to drink and violence, seems to be a more and more obvious suspect. At least until Dr Priestley takes an interest in the case. What seemed like an open-and-shut case now proves to be far more complex than anyone could have imagined. The solution to the murder, and to another related murder, is as ingenious as anything you’re likely to come across in golden age detective fiction.

The solution is in fact so intricate as to appear slightly far-fetched but there’s no denying the skill with which the novel is plotted.

D Priestley is in the great tradition of amateur detectives but he has little time for leaps of intuition. He relies on solid facts, on mathematically precise reasoning, and on science. The solution to the murder is, fittingly, very much a product of science.

The style of the book is fairly austere. The novelist and critic Julian Symons classifies Street as belonging to the “humdrum” school of crime fiction, which is perhaps a little unfair. Street certainly treats crime in the same way that Dr Priestley does, as an intellectual puzzle, but it would be unjust to conclude that he was a dull writer. His style gets the job done and is not displeasing. The emphasis is very much on plot (and his plotting is certainly excellent) but Dr Priestley is an interesting character. Street is careful to take the obvious route by making him a grandiose larger-than-life character but he is clearly an exceptional man and his faith in the scientific approach is taken so far as to make him anything but a colourless character.

A very entertaining crime novel, and warmly recommended.

It was one of many books to feature Dr Priestley, although he does not appear in this book until quite late. Dr Priestley, like R. Austin Freeman’s Dr Thorndyke, was a scientific detective. Dr Priestley is a slightly eccentric maverick scientist who has discovered that solving crimes can be a pleasant intellectual diversion. He is not motivated by money, nor by any passionate belief in justice. A crime is merely a puzzle to be solved.

In this case the crime is murder. A Mr Barton is found dead, his skull crushed by a blunt instrument. Mr Barton had been living in seclusion in a house on Tollard Ridge, a house a few miles from the village of Charlton Abbas and accessible only on foot. The town of Lenhaven is about fourteen miles distant. Since the death of his beloved wife he had been living there alone until a Mr and Mrs Hapgood had prevailed upon him to move in with them at Tilford Farm.

Mr Barton had been a wealthy man but quite a generous one and was generally so well liked that no-one can conceive that anyone could have a motive for murdering him. Mrs Hapgood has always referred to Mr Barton as Uncle Sam and regarded him almost as a father although in fact they were not related by blood.

Superintendent King is soon on the scene. Slowly a solution to the crime suggests itself to him. A son who has been disowned by Mr Barton, a young man given to drink and violence, seems to be a more and more obvious suspect. At least until Dr Priestley takes an interest in the case. What seemed like an open-and-shut case now proves to be far more complex than anyone could have imagined. The solution to the murder, and to another related murder, is as ingenious as anything you’re likely to come across in golden age detective fiction.

The solution is in fact so intricate as to appear slightly far-fetched but there’s no denying the skill with which the novel is plotted.

D Priestley is in the great tradition of amateur detectives but he has little time for leaps of intuition. He relies on solid facts, on mathematically precise reasoning, and on science. The solution to the murder is, fittingly, very much a product of science.

The style of the book is fairly austere. The novelist and critic Julian Symons classifies Street as belonging to the “humdrum” school of crime fiction, which is perhaps a little unfair. Street certainly treats crime in the same way that Dr Priestley does, as an intellectual puzzle, but it would be unjust to conclude that he was a dull writer. His style gets the job done and is not displeasing. The emphasis is very much on plot (and his plotting is certainly excellent) but Dr Priestley is an interesting character. Street is careful to take the obvious route by making him a grandiose larger-than-life character but he is clearly an exceptional man and his faith in the scientific approach is taken so far as to make him anything but a colourless character.

A very entertaining crime novel, and warmly recommended.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)