Black Magic is a very early manga by Masamune Shirow. It dates from 1983 so he was in his early twenties at the time. He hadn’t yet developed his mature style but he was already playing around with lots of cool ideas.

This is cyberpunk but very early cyberpunk. The genre was only starting to emerge at this time. Black Magic predates William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer, the novel that really established a firm framework for the genre. The Japanese could be described as early adopters of cyberpunk.

There are seven sections to the book, some described as chapters and some as prologues. This is a world of AIs, bioroids and combat robots. The dividing line between computers, humans, bioroids and robots can be very blurred.

The setting is Venus, the only planet in the solar system in which intelligent life is to be found. The Venusians have built an artificial sun on Earth’s Moon. There is life on Earth but it hasn’t amounted to much. The Venusians have started to establish colonies on some of the other planets.

While it lacks the depth and complexity of his later mangas such as Ghost in the Shell this is very much a Masamune Shirow manga. His trademark interests and obsessions are all here. And he gives us lots of fast-moving violent mayhem.

The first prologue, Black Magic, introduces us to a cute girl who has magical powers. Very heavy-duty magical powers. There’s a super-computer than has created other super-computer. Some of these computers are mere machines, some appear to have consciousness. They’re all named after figures in Greek mythology. The cute magical girl, Duna Typhon, was created by one of these artificial intelligences. To what extent is she human? Are her powers magical or super high tech? These entities are not exactly gods. They are not worshipped as gods. But they are god-like and they do behave like goods.

The first chapter Bowman deals with interplanetary colonisation by the Venusians. The story takes place on one their colonies. A young female investigator named Pandora takes control of a new nuclear submarine. But why would anyone have constructed a ballistic missile submarine on a colony planet?

There’s a second prologue and then we move on to the second chapter, Booby Trap. The MA-66 is an advanced combat robot. Four of them are out of control. They will need to be destroyed. The MA-77 is even more formidable. It has advanced decision-making capabilities. An MA-77 has gone rogue as well. There’s lots of high-octane action in this chapter.

City Light moves the action to Saturn’s moon Titan, or at least to a spaceship on its way there and finding itself in trouble. There are people aboard the spaceship who should not be there. Sabotage may be afoot.

The Epilogue is perhaps unexpected although there have been plenty of clues pointing in this direction.

I always love Masamune Shirow’s footnotes. We don’t get many of those where but we do get some cool endnotes explaining the tech stuff. I love the guy’s playful tongue-in-cheek approach to these. You can tell he has fun doing these mangas.

Masamune Shirow was later slightly embarrassed by the old-fashioned graphic style of this early work. It is a bit old-fashioned but it’s lively.

If there’s a fault here it might be that the author is throwing a few too many ideas into the mix. It’s never quite clear where the magic fits in. He would later move to a more pure cyberpunk style with Appleseed and with Ghost in the Shell he produced one of the towering cyberpunk classics. And he was still in his twenties.

Black Magic’s flaws are actually its strengths. It’s wild and offbeat and surprising. And it’s great fun. Highly recommended.

The Booby Trap chapter was the basis for the 1987 anime OVA Black Magic M-66.

pulp novels, trash fiction, detective stories, adventure tales, spy fiction, etc from the 19th century up to the 1970s

Showing posts with label cyberpunk. Show all posts

Showing posts with label cyberpunk. Show all posts

Tuesday, July 1, 2025

Sunday, February 9, 2025

Ghost In The Shell 1.5: Human-Error Processor

Ghost In The Shell 1.5: Human-Error Processor was the third of Masamune Shirow’s Ghost In The Shell mangas to be published (in 2003) but should be read before Ghost in the Shell 2: Man-Machine Interface (published in 2001).

Human-Error Processor is not so much a graphic novel as a group of short stories, but with some connecting tissue.

Fat Cat dates from 1991. Dead people are being used as cyber-zombies, manipulated by remote control. A young woman fears this fate may have befallen her father although she cannot (or will not) believe he is really dead.

Drive Slave dates from 1992. Azuma and Togusa have to keep a witness alive. The witness’s brain may have been infiltrated by micro-machines. This could be linked to a push to allow prefectural governments access to the very top secret data stored in Pandora. Not everyone is happy with this plan which has the potential to be a major security risk.

The Major has another priority - rescuing the kidnapped girlfriend of a top scientist.

Mines of Mind starts with a series of brutal murders. Several of the victims have tattoos, which seem to be military tattoos. There’s some link to a military prison, and to arms dealing.

Section 9 will have to work with military intelligence on this case. One thing that crops up again and again in the Ghost in the Shell universe is that when you have multiple intelligence agencies they are more likely to work against each other than with each other. There is no trust or goodwill between these agencies.

Human-Error Processor is not so much a graphic novel as a group of short stories, but with some connecting tissue.

Fat Cat dates from 1991. Dead people are being used as cyber-zombies, manipulated by remote control. A young woman fears this fate may have befallen her father although she cannot (or will not) believe he is really dead.

Drive Slave dates from 1992. Azuma and Togusa have to keep a witness alive. The witness’s brain may have been infiltrated by micro-machines. This could be linked to a push to allow prefectural governments access to the very top secret data stored in Pandora. Not everyone is happy with this plan which has the potential to be a major security risk.

The Major has another priority - rescuing the kidnapped girlfriend of a top scientist.

Mines of Mind starts with a series of brutal murders. Several of the victims have tattoos, which seem to be military tattoos. There’s some link to a military prison, and to arms dealing.

Section 9 will have to work with military intelligence on this case. One thing that crops up again and again in the Ghost in the Shell universe is that when you have multiple intelligence agencies they are more likely to work against each other than with each other. There is no trust or goodwill between these agencies.

There’s an added factor - the military has assigned a guy named Kim to the case. Kim and Batou know each other and they do not like each other one little bit.

Lost Past is a hunt for a sniper. It would help if Section 9 knew the identity of the target, but they don’t.

These stories were written in between the publication of the two major Ghost in the Shell mangas and they are much less ambitious. These are routine Section 9 cases, although of course nothing that Section 9 does can really be described as routine.

Public Security Section 9 is a mythical counter-intelligence counter-terrorism unit. It tends to be a bit of a law unto itself. Mr Aramaki, who runs Section 9, doesn’t really take orders from anyone other than the prime minister.

In the original manga the focus was very much on Major Motoko Kusanagi, the female cyborg in charge of Section 9’s field operations. The Major makes appearances in Human-Error Processor but she’s a bit more in the background. Perhaps the intention was to flesh out the other members of the team a bit more, to show that guys like Togusa and Azuma are quite capable of handling routine assignments without need the Major to hold their hands.

There’s also a bit more of a police procedural feel, with an interesting mix of cyberpunk tech and old-fashioned police work (footprint evidence, interviewing witnesses).

Lost Past is a hunt for a sniper. It would help if Section 9 knew the identity of the target, but they don’t.

These stories were written in between the publication of the two major Ghost in the Shell mangas and they are much less ambitious. These are routine Section 9 cases, although of course nothing that Section 9 does can really be described as routine.

Public Security Section 9 is a mythical counter-intelligence counter-terrorism unit. It tends to be a bit of a law unto itself. Mr Aramaki, who runs Section 9, doesn’t really take orders from anyone other than the prime minister.

In the original manga the focus was very much on Major Motoko Kusanagi, the female cyborg in charge of Section 9’s field operations. The Major makes appearances in Human-Error Processor but she’s a bit more in the background. Perhaps the intention was to flesh out the other members of the team a bit more, to show that guys like Togusa and Azuma are quite capable of handling routine assignments without need the Major to hold their hands.

There’s also a bit more of a police procedural feel, with an interesting mix of cyberpunk tech and old-fashioned police work (footprint evidence, interviewing witnesses).

They’re good solid stories and they have plenty of the paranoia that is so much a feature of the Ghost in the Shell universe.

I always love Masamune Shirow’s footnotes - they’re full of esoteric technical stuff but they’re also chatty and whimsical.

Don’t expect Ghost In The Shell 1.5: Human-Error Processor to be quite on the level of the first manga. It’s just a lot less ambitious and low-key, but this is still top-grade cyberpunk. Highly recommended.

I always love Masamune Shirow’s footnotes - they’re full of esoteric technical stuff but they’re also chatty and whimsical.

Don’t expect Ghost In The Shell 1.5: Human-Error Processor to be quite on the level of the first manga. It’s just a lot less ambitious and low-key, but this is still top-grade cyberpunk. Highly recommended.

Kodansha have published this manga in an English translation (in the original right-to-left format).

Friday, August 16, 2024

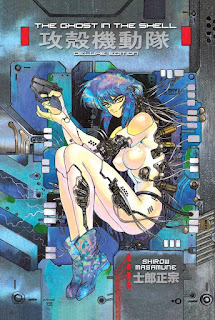

Masamune Shirow's Ghost in the Shell

Ghost in the Shell is a 1989-90 cyberpunk manga (Japanese comic-book) by Masamune Shirow. This is very much a manga for grown-ups.

Cyberpunk emerged as a science fiction sub-genre in the 80s, with the movie Blade Runner in 1982 establishing the aesthetic and William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer and the Bruce Sterling-edited anthology Mirrorshades establishing the thematic framework. Cyberpunk was science fiction focused on the effects of computer technology on human society on Earth rather than on spaceships, photon cannons and aliens.

By the end of the 80s the Japanese were embracing this new sub-genre. In Japan cyberpunk made its appearance in manga and anime rather than in novels and live-action films. This made sense. The Japanese did not have the western prejudice against comic-book and animated movies aimed at adult. And manga and anime were the ideal formats for cyberpunk. There were not particularly restricted by technological or budgetary concerns. The only limitation was the creator’s imagination and the creators of manga and anime had plenty of that.

The anima OVA Cyber City Oedo 808 in 1991 was fully-fledged cyberpunk. The Ghost in the Shell manga was most definitely fully-fledged cyberpunk and would spawn further mangas, several anime feature films (including Mamoru Oshii’s superb 1995 Ghost in the Shell) and an excellent anime TV series.

Major Motoko Kusanagi works for Public Security, Section 9. She leads a top-secret elite squad. Their main brief is counter-terrorist work but in this future world terrorism has become very high-tech and tends to involve hackers, cyborgs, robots and AIs.

The Major herself is a cyborg. She has a human brain and spinal column but everything else is prosthetic. She looks like a normal woman. In this cyberpunk world humans, cyborgs and robots all look human.

Are cyborgs still human? Do robots have rights? Can an AI be alive? These are themes that run right through this manga. These questions are of some personal concern to the Major. Is she a woman or a machine? She feels that she is a woman. She has a woman’s emotions and a woman’s sexual urges. Her body is entirely prosthetic (although it’s fully functional sexually). What matters is the ghost. The body (human or prosthetic) is the shell. The ghost is what makes us alive and makes human.

One of my favourite things about this manga is that Masamune Shirow has provided copious footnotes. Some give fascinating background technical details of this future world. Some provide philosophical musings (this is a manga with a heavy philosophical content). The most interesting offer insight what how the author sees the ghost. The ghost is not quite the soul, at least not in the way we conceive of the soul in countries with a tradition of Christianity. But it’s somewhat akin to a soul. Major Kusanagi is human because she has a ghost. But can an AI have a ghost?

That’s a question that becomes important when she encounters the Puppeteer. It’s not clear what the Puppeteer is but it seems to be a rogue AI. It may have a ghost. This becomes important for Section 9 when it claims political asylum.

The Puppeteer is not confined to a particular body (or shell). But then nor is the Major. She has several spare bodies. Her closest friend and professional colleague Batou has spare bodies as well.

AIs of course are confined to a particular location or body. The Tachikomas, the combat robots used in large numbers by Section 9, are a single AI. Which does not have a ghost. Or at least that’s been the assumption.

Shirow has little or no interest in politics as such but he is interested in power relationships, and politics in this future world is all about power. Mostly however he is interested in philosophical questions (this is a very cerebral manga) which can have a spiritual dimension. In particular he’s fascinated by the philosophical dilemmas that will inevitably arise if and when AIs become self-aware.

The cases Section 9 deals with (the structure of the manga is episodic) mostly hinge on the need to resolve such dilemmas.

It might be cerebral but there’s plenty of action and excitement as well. The Japanese have no problems with the idea of combining big ideas with enjoyable mayhem.

The Major is also interesting because unlike most kickass action heroines she is in a command position. If she makes an incorrect decision people die. Being an action heroine is not a game for her.

Ghost in the Shell really is great stuff - intelligent, provocative, mind-bending, sexy and fun. Very highly recommended.

Cyberpunk emerged as a science fiction sub-genre in the 80s, with the movie Blade Runner in 1982 establishing the aesthetic and William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer and the Bruce Sterling-edited anthology Mirrorshades establishing the thematic framework. Cyberpunk was science fiction focused on the effects of computer technology on human society on Earth rather than on spaceships, photon cannons and aliens.

By the end of the 80s the Japanese were embracing this new sub-genre. In Japan cyberpunk made its appearance in manga and anime rather than in novels and live-action films. This made sense. The Japanese did not have the western prejudice against comic-book and animated movies aimed at adult. And manga and anime were the ideal formats for cyberpunk. There were not particularly restricted by technological or budgetary concerns. The only limitation was the creator’s imagination and the creators of manga and anime had plenty of that.

The anima OVA Cyber City Oedo 808 in 1991 was fully-fledged cyberpunk. The Ghost in the Shell manga was most definitely fully-fledged cyberpunk and would spawn further mangas, several anime feature films (including Mamoru Oshii’s superb 1995 Ghost in the Shell) and an excellent anime TV series.

Major Motoko Kusanagi works for Public Security, Section 9. She leads a top-secret elite squad. Their main brief is counter-terrorist work but in this future world terrorism has become very high-tech and tends to involve hackers, cyborgs, robots and AIs.

The Major herself is a cyborg. She has a human brain and spinal column but everything else is prosthetic. She looks like a normal woman. In this cyberpunk world humans, cyborgs and robots all look human.

Are cyborgs still human? Do robots have rights? Can an AI be alive? These are themes that run right through this manga. These questions are of some personal concern to the Major. Is she a woman or a machine? She feels that she is a woman. She has a woman’s emotions and a woman’s sexual urges. Her body is entirely prosthetic (although it’s fully functional sexually). What matters is the ghost. The body (human or prosthetic) is the shell. The ghost is what makes us alive and makes human.

One of my favourite things about this manga is that Masamune Shirow has provided copious footnotes. Some give fascinating background technical details of this future world. Some provide philosophical musings (this is a manga with a heavy philosophical content). The most interesting offer insight what how the author sees the ghost. The ghost is not quite the soul, at least not in the way we conceive of the soul in countries with a tradition of Christianity. But it’s somewhat akin to a soul. Major Kusanagi is human because she has a ghost. But can an AI have a ghost?

That’s a question that becomes important when she encounters the Puppeteer. It’s not clear what the Puppeteer is but it seems to be a rogue AI. It may have a ghost. This becomes important for Section 9 when it claims political asylum.

The Puppeteer is not confined to a particular body (or shell). But then nor is the Major. She has several spare bodies. Her closest friend and professional colleague Batou has spare bodies as well.

AIs of course are confined to a particular location or body. The Tachikomas, the combat robots used in large numbers by Section 9, are a single AI. Which does not have a ghost. Or at least that’s been the assumption.

Shirow has little or no interest in politics as such but he is interested in power relationships, and politics in this future world is all about power. Mostly however he is interested in philosophical questions (this is a very cerebral manga) which can have a spiritual dimension. In particular he’s fascinated by the philosophical dilemmas that will inevitably arise if and when AIs become self-aware.

The cases Section 9 deals with (the structure of the manga is episodic) mostly hinge on the need to resolve such dilemmas.

It might be cerebral but there’s plenty of action and excitement as well. The Japanese have no problems with the idea of combining big ideas with enjoyable mayhem.

The Major is also interesting because unlike most kickass action heroines she is in a command position. If she makes an incorrect decision people die. Being an action heroine is not a game for her.

Ghost in the Shell really is great stuff - intelligent, provocative, mind-bending, sexy and fun. Very highly recommended.

I’ve reviewed Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell movie elsewhere, as well as the first season of the Ghost in the Shell Stand Alone Complex TV series.

Saturday, June 29, 2024

J.D. Masters' Cold Steele

Cold Steele, published in 1989, is the second of the Steele books by J.D. Masters.

I went into Cold Steele expecting a violent but fun pulp action thriller in the men’s adventure mode. It is in fact a very successful adrenalin-rush pulp action thriller but it’s also a surprisingly smart and interesting and somewhat complex cyberpunk science fiction novel.

The hero is a cyborg, but he’s not a robot with a human brain. He’s a partially robotically enhanced flesh-and-blood man but the twist is that he doesn’t have a human brain. He has a computer brain. Well, it’s sort of a computer brain and sort of a human brain.

Donovan Steele was (and maybe is) a cop who got badly shot up. His body survived. It was badly mangled but with bionic enhancements it was made fully functional. His brain however did not survive. Not on organic form. His personality was however uploaded and used as the basis for the software that drives his electronic brain.

This personality uploading idea was very fashionable in the cyberpunk sci-fi of the 80s. It’s an idea that always struck me as very unconvincing. Masters however handles it rather deftly and in a genuinely provocative and interesting way. Donovan Steele doesn’t know if he’s human or not. He has his human memories. He experiences human emotions. Or at least he thinks he does. But he knows he’s not human in the way other people are human.

And he has some problems, which psychiatrist Dev Cooper is supposed to be helping him work through. Steele has nightmares. These seem to be memories. Very vivid memories. He is convinced that they are real memories. The trouble is that they’re not his memories.

Dev Cooper has problems as well. Ethical problems. He’s been working with a digital copy of Donovan Steele’s personality. This is a Donovan Steele who exists only in digital form, with no physical existence. Dev’s problem is that he has to decide if this digital copy is alive. Does it have rights?

This is also a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel. The world has been devastated by viruses and nuclear war. Large parts of the United States are nothing but radioactive wastelands. Significant parts of the country are controlled by crime gangs who are essentially warlords. Texas has declared its independence. Nobody knows if anybody is still alive in California because nobody has dared to investigate. The federal government wants to reassert its authority and sees cyborgs like Donovan Steele as a way to do this. One cyborg is as effective as a whole squad of cops, and much cheaper. The government doesn’t care about the ethical issues. It just wants power and control.

Donovan Steele’s assignment in this novel is to take down the Borodini crime family which controls much of New York. It would take a small army to deal with the Borodini family. They live in a fortress. Steele figures he can do the job himself.

He has some help. Ice is a black former gang leader who has agreed to help in return for immunity from prosecution. Steele and Ice don’t trust each other but they both have something to gain from working together, and Ice can certainly handle himself in a tough spot. Steele’s other ally is Raven, a young hooker whom he rescued. She can be trusted insofar as she has a personal grudge against the Borodinis.

A weird emotional bond develops between Steele and Raven. Steele doesn’t care that she’s a hooker. Raven doesn’t care that he’s a robot. They’re both broken inside but they find, to their own mutual surprise, that they’ve started to care for each other.

Of course this book is part of a series so some issues are left only partially resolved, presumably to be dealt with further in later books.

There’s as much action and mayhem as you could possibly desire, combined with a strange love story and some surprisingly deep emotional, moral and intellectual speculation. Some of these issues would also be dealt with a few years later in the excellent Japanese sci-fi anime movie Ghost in the Shell.

I enjoyed this novel enough to leave me quite open to the idea of buying the next book in the series.

Cold Steele is highly recommended.

I went into Cold Steele expecting a violent but fun pulp action thriller in the men’s adventure mode. It is in fact a very successful adrenalin-rush pulp action thriller but it’s also a surprisingly smart and interesting and somewhat complex cyberpunk science fiction novel.

The hero is a cyborg, but he’s not a robot with a human brain. He’s a partially robotically enhanced flesh-and-blood man but the twist is that he doesn’t have a human brain. He has a computer brain. Well, it’s sort of a computer brain and sort of a human brain.

Donovan Steele was (and maybe is) a cop who got badly shot up. His body survived. It was badly mangled but with bionic enhancements it was made fully functional. His brain however did not survive. Not on organic form. His personality was however uploaded and used as the basis for the software that drives his electronic brain.

This personality uploading idea was very fashionable in the cyberpunk sci-fi of the 80s. It’s an idea that always struck me as very unconvincing. Masters however handles it rather deftly and in a genuinely provocative and interesting way. Donovan Steele doesn’t know if he’s human or not. He has his human memories. He experiences human emotions. Or at least he thinks he does. But he knows he’s not human in the way other people are human.

And he has some problems, which psychiatrist Dev Cooper is supposed to be helping him work through. Steele has nightmares. These seem to be memories. Very vivid memories. He is convinced that they are real memories. The trouble is that they’re not his memories.

Dev Cooper has problems as well. Ethical problems. He’s been working with a digital copy of Donovan Steele’s personality. This is a Donovan Steele who exists only in digital form, with no physical existence. Dev’s problem is that he has to decide if this digital copy is alive. Does it have rights?

This is also a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel. The world has been devastated by viruses and nuclear war. Large parts of the United States are nothing but radioactive wastelands. Significant parts of the country are controlled by crime gangs who are essentially warlords. Texas has declared its independence. Nobody knows if anybody is still alive in California because nobody has dared to investigate. The federal government wants to reassert its authority and sees cyborgs like Donovan Steele as a way to do this. One cyborg is as effective as a whole squad of cops, and much cheaper. The government doesn’t care about the ethical issues. It just wants power and control.

Donovan Steele’s assignment in this novel is to take down the Borodini crime family which controls much of New York. It would take a small army to deal with the Borodini family. They live in a fortress. Steele figures he can do the job himself.

He has some help. Ice is a black former gang leader who has agreed to help in return for immunity from prosecution. Steele and Ice don’t trust each other but they both have something to gain from working together, and Ice can certainly handle himself in a tough spot. Steele’s other ally is Raven, a young hooker whom he rescued. She can be trusted insofar as she has a personal grudge against the Borodinis.

A weird emotional bond develops between Steele and Raven. Steele doesn’t care that she’s a hooker. Raven doesn’t care that he’s a robot. They’re both broken inside but they find, to their own mutual surprise, that they’ve started to care for each other.

Of course this book is part of a series so some issues are left only partially resolved, presumably to be dealt with further in later books.

There’s as much action and mayhem as you could possibly desire, combined with a strange love story and some surprisingly deep emotional, moral and intellectual speculation. Some of these issues would also be dealt with a few years later in the excellent Japanese sci-fi anime movie Ghost in the Shell.

I enjoyed this novel enough to leave me quite open to the idea of buying the next book in the series.

Cold Steele is highly recommended.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)