E. Howard Hunt (1918-2007) is best-known for being one of the Watergate conspirators. He was a career CIA agent. He was also a popular and successful and extremely prolific novelist, mostly in the crime and spy genres. He had an exceptionally long career as a writer. His first novel was published in 1942; his final novel was written in 2000.

Using the pseudonym David St. John he wrote ten Peter Ward spy thrillers between 1965 and 1972.

The final three Peter Ward thrillers marked a slight change in direction. They were both spy thrillers and occult thrillers. These three books included Diabolus, published in 1971.

Diabolus opens on the small French-Controlled Caribbean island of Lapoire. Peter Ward is on holidays. He’s thoroughly enjoying himself, until his young black housekeeper Dominique disappears. And is found dead. She had been brutally sexually assaulted. The police assume she committed suicide as a result of the rape, and they obviously do not intend to investigate any further.

Peter is very unhappy about this. It’s not that he had anything other than a straightforward employer-employee relationship with Dominique. But she was a nice girl. And Peter doesn’t like the idea of young girls being raped and murdered. He does not believe the suicide theory. And he doesn’t like unsolved mysteries.

He’s even more unhappy after talking with the cop in charge of the case, Commissaire Ducamp. Ducamp’s indifference to Dominique’s fate bothers him a lot.

Peter decided to do some investigating on his own, which has very unexpected consequences. A few days later he is back in Washington, about to be sent on a totally unrelated mission to Paris. It’s a very delicate mission. The wife of the French Foreign Minister is being blackmailed. This would normally be none of the CIA’s business, except that relation between the US and France have been slightly strained and the CIA fears that a scandal involving France’s Foreign Minister could make it difficult to improve those relations.

Peter’s job is to free the Foreign Minister’s wife (her name is Simone de Marchais) from the blackmail threat. Peter is given to understand that he can use whatever methods he thinks necessary but it must be done discreetly. The French must have no inkling of the CIA’s involvement.

There are certain compromising photographs of Simone de Marchais in existence. Not just your regular sex stuff, but showing her involved in Satanic rites and Satanic sex orgies. That’s about all Peter has to go on but he feels that Valérie may be able to help. She has very high-powered connections. She is married to a very important very rich man. She is also Peter Ward’s mistress. Peter Ward is one of those spies who likes to combine the serious business of espionage with pleasure.

Peter discovers that Simone really is involved in a diabolical cult and the cultists are dangerous people to mess with, as he soon finds out. It’s a cult that involves devil-worship, sex and mind-altering drugs. And probably murder.

All of this has no connection with those curious events on that tiny Caribbean island. At least Peter doesn’t see a connection at first. But of course there is a connection.

Since the author was a senior CIA agent it’s not surprising that Peter Ward never questions the idea that the CIA are the good guys. But that could be said about most American (and British) spy fiction of that era. Hunt does not allow his political views to be the slightest bit intrusive. As a writer he was in the business of writing entertaining commercial fiction.

The plot has some nice twists and the spy and occult elements are woven together seamlessly. Spy fans and occult thriller fans should be equally pleased by this book. The plot might be far-fetched, but the real-life world of espionage could be pretty far-fetched as well.

As a career spy Hunt certainly knows how the world in intelligence agencies works, and having been a high-ranking CIA officer he understood the world of international intrigue.

As to whether we’re supposed to take any of the diabolism seriously, you’ll have to read the book to find that out.

Hunt was a perfectly competent writer. His prose isn’t dazzling but it’s solid enough, he understands suspense and he understands action scenes.

There’s just enough sex and sensationalism to add spice without dominating the story. It’s a wonderfully lurid tale which doesn’t quite cross over into the sexy spy thriller sub-genre but at times it comes close.

And it’s great fun. Highly recommended.

I’ve reviewed several of Hunt’s other books including his excellent hardboiled crime novel House Dick, his noirish thriller The Violent Ones and one of his earlier Peter Ward spy novels, One of Our Agents Is Missing. They're all worth reading.

pulp novels, trash fiction, detective stories, adventure tales, spy fiction, etc from the 19th century up to the 1970s

Monday, May 29, 2023

Saturday, May 27, 2023

The Saint Goes West

The Saint Goes West is a 1942 collection of three Saint novellas by Leslie Charteris. Although he wrote fine novels and short stories I’ve always felt that the novella was the perfect form for Charteris. In this collection he demonstrates his complete mastery of the form.

The three novellas are Arizona, Palm Springs and Hollywood.

Leslie Charteris wrote a huge number of Saint stories from the late 1920s up to the early 1960s. The Saint went through several quite distinct incarnations during this time. For my money the most satisfactory versions of the Saint were the first version and the final version. In his initial incarnation Simon Templar is very young, dashing, reckless, carefree, irresponsible and irrepressible. He’s like an overgrown schoolboy, but a charming schoolboy. His sense of fun is infectious. He’s the leader of a criminal gang but they only steal from other criminals and spend more time fighting crime than committing it. Simon acquires a live-in girlfriend, Patricia Holm, and she is the great love of his life. The original version of the Saint is to be found in books such as The Saint Closes the Case and The Avenging Saint.

In his final incarnation he hasn’t aged much physically (he should be in his sixties in his final adventures but he always apparently remains in his thirties) but he’s grown up. He’s now a loner. He seems quite a bit older. He is wiser, and perhaps just a bit sadder. There’s just the faintest hint of melancholy. He is still recognisably the same man, but he has grown up. He has gained some depth. His thirst for adventure remains unquenched although at times you get the vague feeling that he is not entirely comfortable in the postwar world and the adventures are his way of coping with a duller, greyer, more conformist world. This version of Simon Templar can be seen fully formed in the 1948 story collection Saint Errant.

But in between there were a couple of other versions of the Saint. There is the Saint transplanted to America in the late 30s. And The Saint Goes West gives us another one of these transitional editions of Simon Templar.

Simon has been slightly Americanised (not surprising since Charteris had relocated to America and had become hugely popular there). I don’t think this version of the characters works quite as well as the earlier or later versions. He’s lost some of the over-the-top fun quality of the first version and hasn’t yet acquired the substance of the later Saint. But he’s still the Saint and he’s still entertaining.

On the plus side Charteris was at his peak when it came to plotting, especially in Palm Springs and Hollywood. And he uses the American settings extremely well.

In Arizona Simon Templar gets to do the whole cowboy routine. He’s set things up so that he can persuade a rancher to take him on as a hand. The rancher is involved in a dispute with a neighbour who wants to buy the ranch and is prepared to use underhand means to force a sale. The neighbour claims to want to buy the ranch because of a dispute over water rights.

Simon is willing to do the right thing and help out his new employer.

It seems like a classic western story but we suspect from the start that there’s some deeper reasons for the Saint’s presence in Arizona. Since this is a wartime story we further suspect that the reason has something to do with espionage or some dastardly German plot. We already know that Simon suspects that the rancher’s brother was murdered.

Simon finds time to strike up a bit of a romance with the rancher’s daughter.

It gradually becomes obvious that there’s a lot more at stake than water rights, and that the situation is likely to get very ugly.

This is the least successful of the three stories.

Palm Springs has an interesting history. Charteris wrote a screenplay for the RKO Saint series, called The Saint in Palm Springs. By the time the movie was shot there was nothing left of Charteris’s story. In 1941 Charteris wrote a photo-story (told with text and photos) for Life magazine. The story was called Palm Springs. Everybody, including Charteris himself, loved it. So he decided to use it as the basis for the novella Palm Springs.

A rich dissolute young man named Freddie Pellman hires Simon as a bodyguard. He thinks that a mobster is intending to have him rubbed out. Freddie lives in a palatial rambling house in Palm Springs with his harem. Yes, he has a harem. It comprises a blonde, a brunette and a redhead. It’s not always the same blonde, brunette and redhead but there’s always one of each. And no, they’re not just house guests or personal assistants or anything like that. It’s a real harem. The three girls all share Freddie’s bed (although not all at the same time). At this moment the harem comprises Esther, Ginny and Lissa.

Sure enough somebody does try to kill Freddie (he has a narrow escape). The Saint thinks it was an inside job. Which means the assassin has to be one of the three girls, or one of the three servants in the house. And for various reasons the servants seem unlikely suspects. So it’s probably one of the girls. All three are at least vaguely possible suspects.

They all have alibis, but the alibis are not too solid. And Simon doesn’t put too much stock in alibis. He’s made use of alibis himself and he knows how slippery they can be. The alibis do however play a part in the story.

It’s a fine little plot. There’s a somewhat decadent atmosphere, with a cast of colourful offbeat characters and as so often Charteris gets the tone just right - not too serious, not too whimsical. An excellent story.

In Hollywood Simon is offered a job by movie producer Byron Ufferlitz (he used to be a racketeer and now he’s in a different racket). He is rather taken aback when he finds out that he is being groomed for movie stardom. He isn’t sure he wants to be a a screen idol but working at a film studio has its compensations. Ufferlitz has a charming pretty secretary, Peggy Warden. And for publicity purposes Simon has to pretend to romance starlet April Quest. Since she’s also very pretty Simon decides Hollywood isn’t too bad a place.

There’s plenty of drama at the studio, provided not just by ex-racketeer producers and glamorous starlets but also by a couple of crazy screenwriters named Lazaroff and Kendricks, a director named Jack Groom and pretty-boy star Orlando Flane. All of whom have reasons to resent all the others.

So when murder occurs there’s no shortage of suspects. What really concerns Simon is that the police think he’s a suspect as well. So the Saint has a very strong motivation to find the real culprit.

There are some nicely planted clues and as with Palm Springs there’s plenty of misdirection. Another nicely constructed plot and another fine story with a nifty little ending.

So overall, The Saint Goes West does not offer my favourite version of the Saint but it does offer one good story and two excellent very clever stories and those two stories are good enough to lift this book into the highly recommended rating.

And, happily, this book is in print.

The three novellas are Arizona, Palm Springs and Hollywood.

Leslie Charteris wrote a huge number of Saint stories from the late 1920s up to the early 1960s. The Saint went through several quite distinct incarnations during this time. For my money the most satisfactory versions of the Saint were the first version and the final version. In his initial incarnation Simon Templar is very young, dashing, reckless, carefree, irresponsible and irrepressible. He’s like an overgrown schoolboy, but a charming schoolboy. His sense of fun is infectious. He’s the leader of a criminal gang but they only steal from other criminals and spend more time fighting crime than committing it. Simon acquires a live-in girlfriend, Patricia Holm, and she is the great love of his life. The original version of the Saint is to be found in books such as The Saint Closes the Case and The Avenging Saint.

In his final incarnation he hasn’t aged much physically (he should be in his sixties in his final adventures but he always apparently remains in his thirties) but he’s grown up. He’s now a loner. He seems quite a bit older. He is wiser, and perhaps just a bit sadder. There’s just the faintest hint of melancholy. He is still recognisably the same man, but he has grown up. He has gained some depth. His thirst for adventure remains unquenched although at times you get the vague feeling that he is not entirely comfortable in the postwar world and the adventures are his way of coping with a duller, greyer, more conformist world. This version of Simon Templar can be seen fully formed in the 1948 story collection Saint Errant.

But in between there were a couple of other versions of the Saint. There is the Saint transplanted to America in the late 30s. And The Saint Goes West gives us another one of these transitional editions of Simon Templar.

Simon has been slightly Americanised (not surprising since Charteris had relocated to America and had become hugely popular there). I don’t think this version of the characters works quite as well as the earlier or later versions. He’s lost some of the over-the-top fun quality of the first version and hasn’t yet acquired the substance of the later Saint. But he’s still the Saint and he’s still entertaining.

On the plus side Charteris was at his peak when it came to plotting, especially in Palm Springs and Hollywood. And he uses the American settings extremely well.

In Arizona Simon Templar gets to do the whole cowboy routine. He’s set things up so that he can persuade a rancher to take him on as a hand. The rancher is involved in a dispute with a neighbour who wants to buy the ranch and is prepared to use underhand means to force a sale. The neighbour claims to want to buy the ranch because of a dispute over water rights.

Simon is willing to do the right thing and help out his new employer.

It seems like a classic western story but we suspect from the start that there’s some deeper reasons for the Saint’s presence in Arizona. Since this is a wartime story we further suspect that the reason has something to do with espionage or some dastardly German plot. We already know that Simon suspects that the rancher’s brother was murdered.

Simon finds time to strike up a bit of a romance with the rancher’s daughter.

It gradually becomes obvious that there’s a lot more at stake than water rights, and that the situation is likely to get very ugly.

This is the least successful of the three stories.

Palm Springs has an interesting history. Charteris wrote a screenplay for the RKO Saint series, called The Saint in Palm Springs. By the time the movie was shot there was nothing left of Charteris’s story. In 1941 Charteris wrote a photo-story (told with text and photos) for Life magazine. The story was called Palm Springs. Everybody, including Charteris himself, loved it. So he decided to use it as the basis for the novella Palm Springs.

A rich dissolute young man named Freddie Pellman hires Simon as a bodyguard. He thinks that a mobster is intending to have him rubbed out. Freddie lives in a palatial rambling house in Palm Springs with his harem. Yes, he has a harem. It comprises a blonde, a brunette and a redhead. It’s not always the same blonde, brunette and redhead but there’s always one of each. And no, they’re not just house guests or personal assistants or anything like that. It’s a real harem. The three girls all share Freddie’s bed (although not all at the same time). At this moment the harem comprises Esther, Ginny and Lissa.

Sure enough somebody does try to kill Freddie (he has a narrow escape). The Saint thinks it was an inside job. Which means the assassin has to be one of the three girls, or one of the three servants in the house. And for various reasons the servants seem unlikely suspects. So it’s probably one of the girls. All three are at least vaguely possible suspects.

They all have alibis, but the alibis are not too solid. And Simon doesn’t put too much stock in alibis. He’s made use of alibis himself and he knows how slippery they can be. The alibis do however play a part in the story.

It’s a fine little plot. There’s a somewhat decadent atmosphere, with a cast of colourful offbeat characters and as so often Charteris gets the tone just right - not too serious, not too whimsical. An excellent story.

In Hollywood Simon is offered a job by movie producer Byron Ufferlitz (he used to be a racketeer and now he’s in a different racket). He is rather taken aback when he finds out that he is being groomed for movie stardom. He isn’t sure he wants to be a a screen idol but working at a film studio has its compensations. Ufferlitz has a charming pretty secretary, Peggy Warden. And for publicity purposes Simon has to pretend to romance starlet April Quest. Since she’s also very pretty Simon decides Hollywood isn’t too bad a place.

There’s plenty of drama at the studio, provided not just by ex-racketeer producers and glamorous starlets but also by a couple of crazy screenwriters named Lazaroff and Kendricks, a director named Jack Groom and pretty-boy star Orlando Flane. All of whom have reasons to resent all the others.

So when murder occurs there’s no shortage of suspects. What really concerns Simon is that the police think he’s a suspect as well. So the Saint has a very strong motivation to find the real culprit.

There are some nicely planted clues and as with Palm Springs there’s plenty of misdirection. Another nicely constructed plot and another fine story with a nifty little ending.

So overall, The Saint Goes West does not offer my favourite version of the Saint but it does offer one good story and two excellent very clever stories and those two stories are good enough to lift this book into the highly recommended rating.

And, happily, this book is in print.

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

W.R. Burnett's High Sierra

High Sierra is a 1940 novel by W.R. Burnett (1899-1982), one of the great hardboiled American crime writers.

Roy Earle is thirty-seven and he’s just out of prison. And he’s already involved in another planned job, a hotel heist. Roy had been a big shot. He’d been one of Dillinger’s gang. Six years behind bars hasn’t done him much good. He’s still tough and dangerous, but now he’s fatalistic and obsessed with death. He’s tired.

The job should be easy. This hotel has never been robbed before and supposedly the local police force is practically non-existent.

Roy has to meet up with the other guys in on the job, in an isolated cabin in the Sierras. Red and Babe are young punks and Roy despises them. And they figure he’s old and he’s probably gone soft. What worries Earle is the girl with them, Marie. She’s Babe’s girl. Roy doesn’t ant women involved. Dames always cause trouble and what usually happens is that the men end up at each other’s throats.

The easiness of the job is the problem. It will be easy if nothing unexpected happens. But something unexpected always happens. There’s an overwhelming sense of impending disaster to this book. Roy is the smartest guy involved in this caper, and he’s as dumb as a rock. The other guys ere even dumber. These are guys with no ability whatsoever to look ahead. They want the robbery to go smoothly so they assume it will go smoothly. When things go wrong they have no idea what to do. And they have no idea why things went wrong. Roy puts it down to dumb luck, or fate. He has never considered that his criminal career has been a failure because he just isn’t smart enough. On one level he knows that guys like him always get caught, but he doesn’t have the imagination or the drive to try anything else.

Roy suffers from an extraordinary lack of self-awareness. He thinks a lot about his childhood. He remembers it as an idyllic time. The fact that even when he was a kid people were scared of him because of his violence is something he has edited out of his memories. He believes that he tried getting regular job and making an honest living, but in fact he got fired from every job for being a bad-tempered trouble-maker. He’s also edited that out of his memories.

He has no awareness of his own limitations. He also can’t see that with the accomplices he’s been stuck with the job will inevitably go wrong.

If there was no more to Roy than this then he’d be a very uninteresting character. But there is more to him. He genuinely likes women. In his own clumsy way he’s kind and considerate towards them. He genuinely comes to love Marie. He even makes a start on understanding her.

He has his own weird moral compass. Some of the bad mistakes he makes are due to this. There are times when he just can’t bring himself to be sufficiently ruthless. He doesn’t really like killing.

The heist comes a long way into the book. The main focus is on what makes Roy Earle tick. This is noir fiction but it’s very much psychological noir. And we do get to know Roy Earle very well. We almost feel sorry for him as we see his characters flaws leading him to disaster, and we feel that maybe he doesn’t entirely deserve what seems like being his inevitable fate. There’s just enough good in Roy to make us feel that maybe, if he could make just one smart decision, his life might be salvageable.

There’s not a huge amount of action in this novel. There is plenty of suspense however. The reader can see all the mistakes Roy makes and can anticipate the consequences. Roy either cannot foresee those consequences, or in some cases (more interestingly) he does know he’s bungling things but he goes ahead anyway because he just doesn’t know what else to do.

The obvious question is whether Roy has a death wish. At times it seems that he does, but that changes slightly as his relationship with Marie develops. For the first time in his life he has something to live for. But he knows it’s probably come too late.

High Sierra is a fine novel that manages to pack an emotional punch despite characters who are not obviously all that sympathetic. Perhaps end up caring about Roy and Marie because they are so very flawed. Highly recommended.

Roy Earle is thirty-seven and he’s just out of prison. And he’s already involved in another planned job, a hotel heist. Roy had been a big shot. He’d been one of Dillinger’s gang. Six years behind bars hasn’t done him much good. He’s still tough and dangerous, but now he’s fatalistic and obsessed with death. He’s tired.

The job should be easy. This hotel has never been robbed before and supposedly the local police force is practically non-existent.

Roy has to meet up with the other guys in on the job, in an isolated cabin in the Sierras. Red and Babe are young punks and Roy despises them. And they figure he’s old and he’s probably gone soft. What worries Earle is the girl with them, Marie. She’s Babe’s girl. Roy doesn’t ant women involved. Dames always cause trouble and what usually happens is that the men end up at each other’s throats.

The easiness of the job is the problem. It will be easy if nothing unexpected happens. But something unexpected always happens. There’s an overwhelming sense of impending disaster to this book. Roy is the smartest guy involved in this caper, and he’s as dumb as a rock. The other guys ere even dumber. These are guys with no ability whatsoever to look ahead. They want the robbery to go smoothly so they assume it will go smoothly. When things go wrong they have no idea what to do. And they have no idea why things went wrong. Roy puts it down to dumb luck, or fate. He has never considered that his criminal career has been a failure because he just isn’t smart enough. On one level he knows that guys like him always get caught, but he doesn’t have the imagination or the drive to try anything else.

Roy suffers from an extraordinary lack of self-awareness. He thinks a lot about his childhood. He remembers it as an idyllic time. The fact that even when he was a kid people were scared of him because of his violence is something he has edited out of his memories. He believes that he tried getting regular job and making an honest living, but in fact he got fired from every job for being a bad-tempered trouble-maker. He’s also edited that out of his memories.

He has no awareness of his own limitations. He also can’t see that with the accomplices he’s been stuck with the job will inevitably go wrong.

If there was no more to Roy than this then he’d be a very uninteresting character. But there is more to him. He genuinely likes women. In his own clumsy way he’s kind and considerate towards them. He genuinely comes to love Marie. He even makes a start on understanding her.

He has his own weird moral compass. Some of the bad mistakes he makes are due to this. There are times when he just can’t bring himself to be sufficiently ruthless. He doesn’t really like killing.

The heist comes a long way into the book. The main focus is on what makes Roy Earle tick. This is noir fiction but it’s very much psychological noir. And we do get to know Roy Earle very well. We almost feel sorry for him as we see his characters flaws leading him to disaster, and we feel that maybe he doesn’t entirely deserve what seems like being his inevitable fate. There’s just enough good in Roy to make us feel that maybe, if he could make just one smart decision, his life might be salvageable.

There’s not a huge amount of action in this novel. There is plenty of suspense however. The reader can see all the mistakes Roy makes and can anticipate the consequences. Roy either cannot foresee those consequences, or in some cases (more interestingly) he does know he’s bungling things but he goes ahead anyway because he just doesn’t know what else to do.

The obvious question is whether Roy has a death wish. At times it seems that he does, but that changes slightly as his relationship with Marie develops. For the first time in his life he has something to live for. But he knows it’s probably come too late.

High Sierra is a fine novel that manages to pack an emotional punch despite characters who are not obviously all that sympathetic. Perhaps end up caring about Roy and Marie because they are so very flawed. Highly recommended.

Saturday, May 20, 2023

Ice City of the Gorgon

Ice City of the Gorgon is a science fiction novel by Richard S. Shaver (1907-1975) and Chester S. Geier (1921-1990), originally published in Amazing Stories in 1948.

As well as being science fiction this is also a lost world tale, one of my favourite genres.

A US Navy maritime patrol aircraft is engaged in a search in the Antarctic. A similar aircraft was reported missing a few days earlier. There is little hope of finding the two missing crew members alive but Lieutenant Rick Stacey and Lieutenant jg Phil Tobin are determined to try. They find the wreckage of the missing aircraft. No-one could have survived such a crash. And then Stacey’s plane suffers engine failure. It seems that Stacey and Tobin are destined for an icy grave as well. They do however manage to make an emergency landing.

And they find something very odd. A series of pillars, which they initially assume are pillars of ice. In the distance is what looks like a city. And inside the pillars are people. The first pillar they come to contains a beautiful naked girl. She has been chained. The other pillars all contain people as well.

The pillars are not made of ice but of some mysterious transparent substance. The most startling thing of all is that the people inside the pillars are still alive.

Things get stranger. A huge disembodied head appears, with snake-like protuberances. Rick Stacey knows his Greek mythology well enough for the similarities to the Gorgon to occur to him. And he’s on the right track. Rick and Phil are imprisoned in pillars as well, and Rick discovers that he communicate telepathically with the beautiful naked girl. She’s a princess. Her name is Verla. Rick realises that he’s going to fall hopelessly in love with her.

That disembodied head really was the origin of the Gorgon legend, but it is not of this world.

Then the high priestess Koryl appears. She’s just as gorgeous as Verla, except that she’s evil. And she clearly intends to seduce poor Rick. There’s a major power struggle going on in the city, and it’s complicated. There’s Verla, there’s Koryl, there’s Koryl’s lover Zarduc and there’s the Gorgon and they all have their own agendas.

Maybe it would be more sensible for Rick and Phil to try to escape. Their plane is still operational. But it’s not every day that a guy like Rick meets a stunning nude princess and it has an effect on him. He has to help her. Which means getting mixed up in that power struggle. The most difficult thing will be to prevent Koryl from enticing him into her bed.

Rick is a fairy standard pulp hero type and most of the characters are pretty much stock characters.

The style is pulpy and breathless, which is fine by me. The pacing is pleasingly brisk.

There’s nothing terribly startling here although the use of Greek mythology references is clever enough. But you have a brave hero, a beautiful virtuous princess in distress, a beautiful evil high priestess, a frightening monster, an exotic setting, a lost city, a labyrinth of tunnels under the city, a portal between dimensions, flying bubble cars, swordplay, knife fights, plenty of action and mayhem, a bit of sexiness. With those ingredients any halfway decent author could hardly go wrong, and Geier and Shaver are clearly quite competent. The result is lots of fun.

I liked Ice City of the Gorgon. Recommended.

Ice City of the Gorgon has been re-issued by Armchair Fiction in one of their excellent two-novel paperback editions, paired with Lester Del Rey’s When the World Tottered.

As well as being science fiction this is also a lost world tale, one of my favourite genres.

A US Navy maritime patrol aircraft is engaged in a search in the Antarctic. A similar aircraft was reported missing a few days earlier. There is little hope of finding the two missing crew members alive but Lieutenant Rick Stacey and Lieutenant jg Phil Tobin are determined to try. They find the wreckage of the missing aircraft. No-one could have survived such a crash. And then Stacey’s plane suffers engine failure. It seems that Stacey and Tobin are destined for an icy grave as well. They do however manage to make an emergency landing.

And they find something very odd. A series of pillars, which they initially assume are pillars of ice. In the distance is what looks like a city. And inside the pillars are people. The first pillar they come to contains a beautiful naked girl. She has been chained. The other pillars all contain people as well.

The pillars are not made of ice but of some mysterious transparent substance. The most startling thing of all is that the people inside the pillars are still alive.

Things get stranger. A huge disembodied head appears, with snake-like protuberances. Rick Stacey knows his Greek mythology well enough for the similarities to the Gorgon to occur to him. And he’s on the right track. Rick and Phil are imprisoned in pillars as well, and Rick discovers that he communicate telepathically with the beautiful naked girl. She’s a princess. Her name is Verla. Rick realises that he’s going to fall hopelessly in love with her.

That disembodied head really was the origin of the Gorgon legend, but it is not of this world.

Then the high priestess Koryl appears. She’s just as gorgeous as Verla, except that she’s evil. And she clearly intends to seduce poor Rick. There’s a major power struggle going on in the city, and it’s complicated. There’s Verla, there’s Koryl, there’s Koryl’s lover Zarduc and there’s the Gorgon and they all have their own agendas.

Maybe it would be more sensible for Rick and Phil to try to escape. Their plane is still operational. But it’s not every day that a guy like Rick meets a stunning nude princess and it has an effect on him. He has to help her. Which means getting mixed up in that power struggle. The most difficult thing will be to prevent Koryl from enticing him into her bed.

Rick is a fairy standard pulp hero type and most of the characters are pretty much stock characters.

The style is pulpy and breathless, which is fine by me. The pacing is pleasingly brisk.

There’s nothing terribly startling here although the use of Greek mythology references is clever enough. But you have a brave hero, a beautiful virtuous princess in distress, a beautiful evil high priestess, a frightening monster, an exotic setting, a lost city, a labyrinth of tunnels under the city, a portal between dimensions, flying bubble cars, swordplay, knife fights, plenty of action and mayhem, a bit of sexiness. With those ingredients any halfway decent author could hardly go wrong, and Geier and Shaver are clearly quite competent. The result is lots of fun.

I liked Ice City of the Gorgon. Recommended.

Ice City of the Gorgon has been re-issued by Armchair Fiction in one of their excellent two-novel paperback editions, paired with Lester Del Rey’s When the World Tottered.

Labels:

1940s,

G,

lost worlds,

pulp fiction,

S,

science fiction

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

Orrie Hitt's As Bad As They Come

As Bad As They Come is a 1959 noirish sleaze novel by Orrie Hitt. It was reprinted in 1962 under the title Mail Order Sex. It was reissued in 2012 by Iconoclassic Books, under its original title.

Orrie Hitt (1916-1975) was a prolific American writer of sleaze fiction but he was more than that. Quite a bit of the sleaze fiction of the 50s and 60s was written by guys who were temporarily slumming it and would go on to have distinguished careers on other fields. Guys like Robert Silverberg, Donald E. Westlake and Lawrence Block. Others spent their whole careers writing sleaze. Orrie Hitt belongs in the latter category, but don’t let that give you the idea he was a mere hack. In his own way he was an artist. And more often than not his novels were as much noir fiction as sleaze fiction. It might be most accurate to describe Hitt as a writer of sleaze noir.

As Bad As They Come is the story of a man named Art who works for a mail order company owned by Horace Stone. It’s a precarious business but lucrative if you knew what you were doing. Horace Stone’s mail order business is very much a thriving concern. And Stone has told Art that he’s planing to retire and that Art can take over the business. Art, like so many noir protagonists, is a guy who sees himself as being on the way up.

Art gets a very generous salary. He’s married to Alice. He makes more than enough to keep them in security and comfort but strangely enough they’re only just keeping their heads above water. The reason is simple. He makes $350 a week but tells Alice he makes two hundred. The rest he keeps for himself. He needs it to finance his hobby. His hobby is women. He has slept with most of the girls in the office. The trouble with women is that if you’re going to sleep with them it can be expensive - buying them dinner, buying drinks (lots of drinks), paying for hotel rooms and so forth.

He’s not worried. The business will be his one day. He’ll have lots of money. He’ll have a Cadillac and a fancy house and a swimming pool. And he’s careful with the dames. He’s careful not to get them into a jam.

Then his latest lady friend, Linda, tells him she’s pregnant. This is a tough break for Art. Even worse, she refuses to have an abortion. And worse still, she wants him to divorce Alice and marry her. He has no intention of doing this.

And then there’s Alice’s sister Sandy. She’s nineteen and she’s got everything a woman should have and all in the right places. Art and Sandy have started sleeping together. Another complication is Jean Carter. He met her on the train and he’s sleeping with her as well. Art is staring to think that maybe he has too many women.

Then Horace Stone tells Art about his latest idea for the business. He wants to branch out into mail order nudie pictures. In puritanical 1950s America where just about everything that made life enjoyable was illegal this is somewhat risky but Horace has talked to a lawyer who has assured him that as long as they’re careful there won’t be problems with the cops.

Clearly Art’s life is a house of cards that could come crashing down at any moment but Art is a guy who doesn’t like to think about unpleasant things. He’s also a guy who figures that the best way to deal with a problem is to ignore it and hope that things will work out. He’s a guy he writes a cheque and doesn’t worry about whether he has enough money in the bank to cover it. He’ll worry about that when the time comes.

Art is like a lot of Hitt’s protagonists. He’s clever, but not as clever as he thinks he is.

This is typical Orrie Hitt stuff and that’s no bad thing. There’s a sleazy atmosphere but there’s quite a bit of noir atmosphere as well as Art becomes more and more trapped by the situations he’s landed himself in.

A good Orrie Hitt novel. Highly recommended.

Orrie Hitt (1916-1975) was a prolific American writer of sleaze fiction but he was more than that. Quite a bit of the sleaze fiction of the 50s and 60s was written by guys who were temporarily slumming it and would go on to have distinguished careers on other fields. Guys like Robert Silverberg, Donald E. Westlake and Lawrence Block. Others spent their whole careers writing sleaze. Orrie Hitt belongs in the latter category, but don’t let that give you the idea he was a mere hack. In his own way he was an artist. And more often than not his novels were as much noir fiction as sleaze fiction. It might be most accurate to describe Hitt as a writer of sleaze noir.

As Bad As They Come is the story of a man named Art who works for a mail order company owned by Horace Stone. It’s a precarious business but lucrative if you knew what you were doing. Horace Stone’s mail order business is very much a thriving concern. And Stone has told Art that he’s planing to retire and that Art can take over the business. Art, like so many noir protagonists, is a guy who sees himself as being on the way up.

Art gets a very generous salary. He’s married to Alice. He makes more than enough to keep them in security and comfort but strangely enough they’re only just keeping their heads above water. The reason is simple. He makes $350 a week but tells Alice he makes two hundred. The rest he keeps for himself. He needs it to finance his hobby. His hobby is women. He has slept with most of the girls in the office. The trouble with women is that if you’re going to sleep with them it can be expensive - buying them dinner, buying drinks (lots of drinks), paying for hotel rooms and so forth.

He’s not worried. The business will be his one day. He’ll have lots of money. He’ll have a Cadillac and a fancy house and a swimming pool. And he’s careful with the dames. He’s careful not to get them into a jam.

Then his latest lady friend, Linda, tells him she’s pregnant. This is a tough break for Art. Even worse, she refuses to have an abortion. And worse still, she wants him to divorce Alice and marry her. He has no intention of doing this.

And then there’s Alice’s sister Sandy. She’s nineteen and she’s got everything a woman should have and all in the right places. Art and Sandy have started sleeping together. Another complication is Jean Carter. He met her on the train and he’s sleeping with her as well. Art is staring to think that maybe he has too many women.

Then Horace Stone tells Art about his latest idea for the business. He wants to branch out into mail order nudie pictures. In puritanical 1950s America where just about everything that made life enjoyable was illegal this is somewhat risky but Horace has talked to a lawyer who has assured him that as long as they’re careful there won’t be problems with the cops.

Clearly Art’s life is a house of cards that could come crashing down at any moment but Art is a guy who doesn’t like to think about unpleasant things. He’s also a guy who figures that the best way to deal with a problem is to ignore it and hope that things will work out. He’s a guy he writes a cheque and doesn’t worry about whether he has enough money in the bank to cover it. He’ll worry about that when the time comes.

Art is like a lot of Hitt’s protagonists. He’s clever, but not as clever as he thinks he is.

This is typical Orrie Hitt stuff and that’s no bad thing. There’s a sleazy atmosphere but there’s quite a bit of noir atmosphere as well as Art becomes more and more trapped by the situations he’s landed himself in.

A good Orrie Hitt novel. Highly recommended.

Saturday, May 13, 2023

Modesty Blaise La Machine, The Long Lever, The Gabriel Set-Up

La Machine was the first-ever Modesty Blaise comic strip, and the first-ever Modesty Blaise story. It’s included, along with the next two adventures, in the first of the Titan Books volumes collecting the comic strips in book form.

Modesty Blaise was not the first kickass action heroine in fiction but she was a very early example of the breed. She was not only one of the most successful such heroines, she is also one of the most interesting.

The Modesty Blaise comic strip first appeared in the London Evening Standard on 13 May 1963. The comic strip ran until 2001. She appeared in eleven novels and two short story collections between 1965 and 1996. There were film and TV adaptations.

Peter O’Donnell seems to have known from the start that he was onto something special. He spent a year developing the character before the first comic strip appeared. He wanted to get her just right and he wanted her to be not just a comic-strip heroine but a complex and fascinating woman.

La Machine is very much a setting up the characters story and O’Donnell therefore keeps the narrative fairly straightforward. Modesty, in retirement after her successful criminal career, is persuaded to take on a job for the British security services. As will become usual it is a shadowy figure in the British Secret Service, Sir Gerald, who offers her the assignment. But Modesty is a freelancer. She is never under any obligation to accept an assignment.

The mission in this case is to expose and destroy an international murder racket known as La Machine, a kind of Murder Inc operation. Modesty’s plan is to tempt the racketeers into seeing her as a potential client. She will have to go further than that, and she lands herself in a very tricky situation. Her motives are suspected and La Machine marks her down for execution.

In this story O’Donnell succeeds in telling us a very great deal about Modesty, about how she operates and how she feels.

In the second story, The Long Lever, the KGB snatches a scientist and the Americans want him back. Sir Gerald hopes to pull off a coup - using Modesty and Willie to beat the Americans to the punch. It’s all a matter of British pride.

It’s a story with an unexpected twist, the first sign that O’Donnell was not always going to conform to out expectations. The twist also tells us a bit more about Modesty, and how her past has affected her.

The third story, The Gabriel Set-Up, taps into themes that were very much in tune with the early 60s zeitgeist - brainwashing and mind control. Super-criminal Gabriel (who has clashed with Modesty in the past, is running a clinic for neurotic rich people. It’s part of a racket dealing in blackmail and industrial espionage, but Gabriel’s plans extend much further than that.

Modesty of course turns up at the clinic as a patient. Considering her past the idea of letting people play with her mind is rather frightening but Modesty is always prepared to endure unpleasantness in order to carry out a mission. And controlling Modesty’s mind is quite a challenge.

The first thing to be said is that Modesty is not a Honey West clone or a Cathy Gale clone. She is also not James Bond in a skirt. She is in some ways more like a female Simon Templar. Like the Saint she has made her fortune from crime. Like the Saint she feels no remorse whatsoever. Again like Simon Templar she figures that she has more than paid back society through her crime-fighting and counter-espionage activities so she has no need to feel any guilt. Like Simon Templar, but to a much greater degree, she is a bit of an outsider. But there’s a lot more to Modesty Blaise.

Modesty knows nothing of her origins. At the end of the war she was a kid in a displaced persons camp in the Middle East. Her dossier in the files in the British security service mentions that she is just very slightly Eurasian in appearance. Modesty speaks several languages and probably doesn’t know what her mother tongue is. She is a British citizen by marriage.

One of the things that makes Modesty interesting is that she’s psychologically damaged. She want through Hell when she was young and she still bears the scars. She has been able to put herself back together again but the damage is still there. It has made her both tougher and, oddly, more vulnerable.

Modesty’s missions always seem to put her in situations in which it’s an absolute certainty that she will be captured, physically abused, tortured and humiliated. And she puts herself in these situations deliberately. She’s not a masochist as such, she doesn’t enjoy it, but she does seem to get a certain amount of satisfaction out of proving that she can take it, and proving that no matter what is done to her it won’t really hurt her because she has developed techniques to switch herself off completely. There’s always a sexual element involved in these situations but Modesty has also trained herself to switch off from that, so that these events never warp her thoroughly natural enjoyment of her sex life.

The backstory also makes the Modesty-Willie Garvin relationship makes and explains why, despite their intense emotional bond and despite the fact that they both have normal healthy sex lives, they cannot ever sleep together. They developed a kind of brother-sister relationship which would be shattered if they had sex.

Another cool thing about Modesty is that she doesn’t just have the usual accomplishments (firearms and unarmed combat skills). She has some psychological tricks she developed in order to survive her nightmare childhood and these tricks often give her an edge over an opponent.

Of all the kickass action heroines of the past sixty years I find Modesty Blaise to be the most convincingly female. She’s an intelligent, resourceful, tough and capable woman, but she is always a woman. As I said earlier, you’ll never mistake her for James Bond in a skirt. She’s also by far the most psychologically and emotionally complex of kickass action heroines. She really is a fascinating woman.

Modesty Blaise is a comic strip for grown-ups. There’s plenty of action and excitement but it offers some subtlety and it explores surprisingly complex themes. Of course these themes, and Modesty’s fascinating personality and motivations, are explored in more depth in the novels but the comic strips have just a bit more depth than you might expect. Highly recommended.

I’ve reviewed several of the Modesty Blaise novels, including the first one and the excellent Sabre-Tooth as well as one of the later entries in the series, Last Day In Limbo.

Modesty Blaise was not the first kickass action heroine in fiction but she was a very early example of the breed. She was not only one of the most successful such heroines, she is also one of the most interesting.

The Modesty Blaise comic strip first appeared in the London Evening Standard on 13 May 1963. The comic strip ran until 2001. She appeared in eleven novels and two short story collections between 1965 and 1996. There were film and TV adaptations.

Peter O’Donnell seems to have known from the start that he was onto something special. He spent a year developing the character before the first comic strip appeared. He wanted to get her just right and he wanted her to be not just a comic-strip heroine but a complex and fascinating woman.

La Machine is very much a setting up the characters story and O’Donnell therefore keeps the narrative fairly straightforward. Modesty, in retirement after her successful criminal career, is persuaded to take on a job for the British security services. As will become usual it is a shadowy figure in the British Secret Service, Sir Gerald, who offers her the assignment. But Modesty is a freelancer. She is never under any obligation to accept an assignment.

The mission in this case is to expose and destroy an international murder racket known as La Machine, a kind of Murder Inc operation. Modesty’s plan is to tempt the racketeers into seeing her as a potential client. She will have to go further than that, and she lands herself in a very tricky situation. Her motives are suspected and La Machine marks her down for execution.

In this story O’Donnell succeeds in telling us a very great deal about Modesty, about how she operates and how she feels.

In the second story, The Long Lever, the KGB snatches a scientist and the Americans want him back. Sir Gerald hopes to pull off a coup - using Modesty and Willie to beat the Americans to the punch. It’s all a matter of British pride.

It’s a story with an unexpected twist, the first sign that O’Donnell was not always going to conform to out expectations. The twist also tells us a bit more about Modesty, and how her past has affected her.

The third story, The Gabriel Set-Up, taps into themes that were very much in tune with the early 60s zeitgeist - brainwashing and mind control. Super-criminal Gabriel (who has clashed with Modesty in the past, is running a clinic for neurotic rich people. It’s part of a racket dealing in blackmail and industrial espionage, but Gabriel’s plans extend much further than that.

Modesty of course turns up at the clinic as a patient. Considering her past the idea of letting people play with her mind is rather frightening but Modesty is always prepared to endure unpleasantness in order to carry out a mission. And controlling Modesty’s mind is quite a challenge.

The first thing to be said is that Modesty is not a Honey West clone or a Cathy Gale clone. She is also not James Bond in a skirt. She is in some ways more like a female Simon Templar. Like the Saint she has made her fortune from crime. Like the Saint she feels no remorse whatsoever. Again like Simon Templar she figures that she has more than paid back society through her crime-fighting and counter-espionage activities so she has no need to feel any guilt. Like Simon Templar, but to a much greater degree, she is a bit of an outsider. But there’s a lot more to Modesty Blaise.

Modesty knows nothing of her origins. At the end of the war she was a kid in a displaced persons camp in the Middle East. Her dossier in the files in the British security service mentions that she is just very slightly Eurasian in appearance. Modesty speaks several languages and probably doesn’t know what her mother tongue is. She is a British citizen by marriage.

One of the things that makes Modesty interesting is that she’s psychologically damaged. She want through Hell when she was young and she still bears the scars. She has been able to put herself back together again but the damage is still there. It has made her both tougher and, oddly, more vulnerable.

Modesty’s missions always seem to put her in situations in which it’s an absolute certainty that she will be captured, physically abused, tortured and humiliated. And she puts herself in these situations deliberately. She’s not a masochist as such, she doesn’t enjoy it, but she does seem to get a certain amount of satisfaction out of proving that she can take it, and proving that no matter what is done to her it won’t really hurt her because she has developed techniques to switch herself off completely. There’s always a sexual element involved in these situations but Modesty has also trained herself to switch off from that, so that these events never warp her thoroughly natural enjoyment of her sex life.

The backstory also makes the Modesty-Willie Garvin relationship makes and explains why, despite their intense emotional bond and despite the fact that they both have normal healthy sex lives, they cannot ever sleep together. They developed a kind of brother-sister relationship which would be shattered if they had sex.

Another cool thing about Modesty is that she doesn’t just have the usual accomplishments (firearms and unarmed combat skills). She has some psychological tricks she developed in order to survive her nightmare childhood and these tricks often give her an edge over an opponent.

Of all the kickass action heroines of the past sixty years I find Modesty Blaise to be the most convincingly female. She’s an intelligent, resourceful, tough and capable woman, but she is always a woman. As I said earlier, you’ll never mistake her for James Bond in a skirt. She’s also by far the most psychologically and emotionally complex of kickass action heroines. She really is a fascinating woman.

Modesty Blaise is a comic strip for grown-ups. There’s plenty of action and excitement but it offers some subtlety and it explores surprisingly complex themes. Of course these themes, and Modesty’s fascinating personality and motivations, are explored in more depth in the novels but the comic strips have just a bit more depth than you might expect. Highly recommended.

I’ve reviewed several of the Modesty Blaise novels, including the first one and the excellent Sabre-Tooth as well as one of the later entries in the series, Last Day In Limbo.

Thursday, May 11, 2023

Clark Ashton Smith's Hyperborea stories

I’ve been a fan of the work of Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961) for years. Smith was a member of Lovecraft’s circle and he’s notable for the extreme ornateness of his prose. Smith’s Hyperborea cycle shows Lovecraft’s influence very strongly and it has definite links to Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos.

Hyperborea is a mythical world with some similarities to Robert E. Howard’s Hyboria. Hyperborea is a world of wizardry and lost prehistoric civilisations.

In The Tale of Satampra Zeiros two thieves set out to loot the treasures of the lost city of Commoriom, a city shunned by all. The thieves soon find out exactly why everybody shuns the ruined city. The city might be dead but the old gods that had been been worshipped there might not be entirely dead. And they are rather savage gods. There’s more excitement than is usual in a Smith story, there’s a superbly evoked atmosphere of decay and malevolence and there are some definite touches of black humour.

The Door to Saturn is literally about a door to Saturn. The sorcerer Eibon is facing charges of heresy and makes his escape from the enraged inquisitor Morghi just in time. Eibon is a devotee of the god Zhothaqquagh and that deity has provided the sorcerer with a very convenient little door that opens on the surface of the planet Saturn. The only downside is, it he uses the door it will be a one-way trip.

Morghi somewhat unwisely follows Eibon through the door. They find that Saturn is a profoundly strange place. It’s not particularly dangerous, just strange.

This is very much a tongue-in-cheek story with a number of elaborate jokes. There’s no real terror and there’s no real action but it is amusing.

The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan is an enjoyable little story about a greedy money-lender chasing two fabulous emeralds. Literally chasing the emeralds, which ran away from him while he was admiring them. The ending is rather neat. You know that something bad is most likely in store for the luckless money-lender but his fate is not quite the one you might be expecting.

The Theft of Thirty-Nine Girdles is a very late story, originally published in 1958. It’s another tale of thievery and although the methods used by the thieves are highly imaginative they do not quite qualify as sorcery. The thirty-nine girdles are chastity girdles belonging to the sacred virgins of the temple of Leniqua. Virgins is perhaps not an entirely accurate description, the young ladies in question being in fact temple prostitutes. Stealing is a difficult enough art. Ensuring that one actually keeps the rewards of thievery is even more challenging but Satampra Zeiros is a thief of vast experience.

The Coming of the White Worm is perhaps the most ambitious of the Hyperborean tales. And the most successful. A galley is cast ashore. The crew members are dead and when the wizard Evagh suggests that the bodies should be burnt he gets a nasty surprise. The bodies will not burn. Then the monstrous iceberg appears. The iceberg houses a god, a gigantic white worm. The worm makes Evagh an offer he is in no position to refuse although he is by no means certain that this god should be trusted. This is a tale of icy terror, of the horror of the cold that is beyond any natural cold, and the horrors do not end there. Smith was always good with atmosphere but in this story he excels himself. A wildly imaginative and disturbing tale.

The Seven Geases is a dark little tale with more than a tinge of black humour. A magistrate and big game hunter falls foul of an ill-tempered sorcerer who imposes a geas (a kind of magical obligation) upon him. Which seems to lead to more and more geases imposed on the luckless magistrate each o0f which requires him to descend further intro the bowels of a magical mountain wherein he keeps encountering more and more strange and unpleasant creatures. This plot gives Smith the opportunity to really go to town on the atmosphere of dread and malevolence and on the general weirdness. Which he does, to marvellous effect.

In The Testament of Athammaus we learn the exact nature of the fate of the once-proud and now deserted city of Commoriom. Athammaus had been the headsman of the city and was proud of his ability to carry out executions with efficiency and certainty. Only once did he fail in his duty, with awful consequences for the city.

Hyperborea is a mythical world with some similarities to Robert E. Howard’s Hyboria. Hyperborea is a world of wizardry and lost prehistoric civilisations.

In The Tale of Satampra Zeiros two thieves set out to loot the treasures of the lost city of Commoriom, a city shunned by all. The thieves soon find out exactly why everybody shuns the ruined city. The city might be dead but the old gods that had been been worshipped there might not be entirely dead. And they are rather savage gods. There’s more excitement than is usual in a Smith story, there’s a superbly evoked atmosphere of decay and malevolence and there are some definite touches of black humour.

The Door to Saturn is literally about a door to Saturn. The sorcerer Eibon is facing charges of heresy and makes his escape from the enraged inquisitor Morghi just in time. Eibon is a devotee of the god Zhothaqquagh and that deity has provided the sorcerer with a very convenient little door that opens on the surface of the planet Saturn. The only downside is, it he uses the door it will be a one-way trip.

Morghi somewhat unwisely follows Eibon through the door. They find that Saturn is a profoundly strange place. It’s not particularly dangerous, just strange.

This is very much a tongue-in-cheek story with a number of elaborate jokes. There’s no real terror and there’s no real action but it is amusing.

The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan is an enjoyable little story about a greedy money-lender chasing two fabulous emeralds. Literally chasing the emeralds, which ran away from him while he was admiring them. The ending is rather neat. You know that something bad is most likely in store for the luckless money-lender but his fate is not quite the one you might be expecting.

The Theft of Thirty-Nine Girdles is a very late story, originally published in 1958. It’s another tale of thievery and although the methods used by the thieves are highly imaginative they do not quite qualify as sorcery. The thirty-nine girdles are chastity girdles belonging to the sacred virgins of the temple of Leniqua. Virgins is perhaps not an entirely accurate description, the young ladies in question being in fact temple prostitutes. Stealing is a difficult enough art. Ensuring that one actually keeps the rewards of thievery is even more challenging but Satampra Zeiros is a thief of vast experience.

The Coming of the White Worm is perhaps the most ambitious of the Hyperborean tales. And the most successful. A galley is cast ashore. The crew members are dead and when the wizard Evagh suggests that the bodies should be burnt he gets a nasty surprise. The bodies will not burn. Then the monstrous iceberg appears. The iceberg houses a god, a gigantic white worm. The worm makes Evagh an offer he is in no position to refuse although he is by no means certain that this god should be trusted. This is a tale of icy terror, of the horror of the cold that is beyond any natural cold, and the horrors do not end there. Smith was always good with atmosphere but in this story he excels himself. A wildly imaginative and disturbing tale.

The Seven Geases is a dark little tale with more than a tinge of black humour. A magistrate and big game hunter falls foul of an ill-tempered sorcerer who imposes a geas (a kind of magical obligation) upon him. Which seems to lead to more and more geases imposed on the luckless magistrate each o0f which requires him to descend further intro the bowels of a magical mountain wherein he keeps encountering more and more strange and unpleasant creatures. This plot gives Smith the opportunity to really go to town on the atmosphere of dread and malevolence and on the general weirdness. Which he does, to marvellous effect.

In The Testament of Athammaus we learn the exact nature of the fate of the once-proud and now deserted city of Commoriom. Athammaus had been the headsman of the city and was proud of his ability to carry out executions with efficiency and certainty. Only once did he fail in his duty, with awful consequences for the city.

Anything by Clark Ashton Smith is worth reading. Not just a great writer of weird fiction but a great writer of decadent literature as well. Highly recommended.

Sunday, May 7, 2023

Edward S. Aarons' Gang Rumble

Gang Rumble is a 1958 juvenile delinquent potboiler written by Edward S. Aarons, using the pseudonym Edward Ronns.

American Edward S. Aarons (1916-1975) is best-remembered for his long-running series of Sam Durell spy thrillers. He wrote around 80 novels in total between 1936 and 1975.

Johnny Broom belongs to a gang, the Lancers. He’s their warlord. He’s ambitious. He has organised a rumble, with the victims being a rival gang. But for Johnny the rumble is just a diversion for a robbery. His accomplices with be a fellow Lancer, Stitch, and a weird kid named Mike. Mike doesn’t quite belong. He’s educated and middle class. Why is he hanging around with punks like Johnny? The answer to that question is the driving force of the plot.

Johnny’s nemesis is a tough crooked drunken cop named Vallera. Vallera hates punks like Johnny. Vallera and his partner have been tipped off about the rumble but Vallera is suspicious. Why would a crook like Comber give him such a tip-off?

Also mixed up in this story is a well-meaning do-gooder who wants to save these juvenile delinquents from themselves.

The robbery naturally doesn’t play out the way Johnny had wanted it to, but it plays out the way Mike had hoped. Johnny has a gun with him, which may have been a bad idea.

There’s plenty of typical 1950s angst about juvenile delinquency and there’s another classic 50s ingredient - an attempt to get inside the head of a dangerous thug.

Johnny is your classic loser, a teenager with ambitions and no brains. Mike is something different. He has some issues. Some of these issues involve women, and involve his relationship with his mother. Yes, this was the 50s so we get hints of pseudo-Freudianism.

It’s a fairly violent story. Out-of-control teenage punks carrying guns will inevitably lead to violence. Both Johnny and Mike are dangerous, but they’re dangerous in different ways. What they have in common is a tendency towards delusions of grandeur. They’re both time bombs waiting to go off.

It’s also a novel that addresses the behaviour of the police. Vallera is in some ways just as dangerous as the teenage punks he hates so much.

This is exciting action-packed pulp fiction but the author also makes a fairly serious attempt to grapple with difficult issues, such as the ways that society tries (and fails) to deal with people who refuse to fit in. Which is an issue that quite a bit of the pulp crime fiction of this era tries to address.

Is it noir fiction? It definitely contains some noir fiction elements. And the ending has a nice noir kind of twist.

The plot works quite effectively, with the tension building as the two young punks get closer and closer to the edge of insanity. Mike and Johnny live in fantasy worlds of their own creation. They’re losers but they think they’re superior.

While Aarons tries to understand the motivations of juvenile delinquents he doesn’t fall for the temptation of sentimentalising them. Maybe it’s a tragedy that kids like this end up the way they do, but they’re still vicious thugs.

This book has been reissued in paperback in Stark House’s Black Gat Books imprint.

I’ve reviewed a couple of the author’s Sam Durell spy novels, Assignment…Suicide and Assignment - Karachi. They’re both worth reading if you’re a spy fiction fan.

American Edward S. Aarons (1916-1975) is best-remembered for his long-running series of Sam Durell spy thrillers. He wrote around 80 novels in total between 1936 and 1975.

Johnny Broom belongs to a gang, the Lancers. He’s their warlord. He’s ambitious. He has organised a rumble, with the victims being a rival gang. But for Johnny the rumble is just a diversion for a robbery. His accomplices with be a fellow Lancer, Stitch, and a weird kid named Mike. Mike doesn’t quite belong. He’s educated and middle class. Why is he hanging around with punks like Johnny? The answer to that question is the driving force of the plot.

Johnny’s nemesis is a tough crooked drunken cop named Vallera. Vallera hates punks like Johnny. Vallera and his partner have been tipped off about the rumble but Vallera is suspicious. Why would a crook like Comber give him such a tip-off?

Also mixed up in this story is a well-meaning do-gooder who wants to save these juvenile delinquents from themselves.

The robbery naturally doesn’t play out the way Johnny had wanted it to, but it plays out the way Mike had hoped. Johnny has a gun with him, which may have been a bad idea.

There’s plenty of typical 1950s angst about juvenile delinquency and there’s another classic 50s ingredient - an attempt to get inside the head of a dangerous thug.

Johnny is your classic loser, a teenager with ambitions and no brains. Mike is something different. He has some issues. Some of these issues involve women, and involve his relationship with his mother. Yes, this was the 50s so we get hints of pseudo-Freudianism.

It’s a fairly violent story. Out-of-control teenage punks carrying guns will inevitably lead to violence. Both Johnny and Mike are dangerous, but they’re dangerous in different ways. What they have in common is a tendency towards delusions of grandeur. They’re both time bombs waiting to go off.

It’s also a novel that addresses the behaviour of the police. Vallera is in some ways just as dangerous as the teenage punks he hates so much.

This is exciting action-packed pulp fiction but the author also makes a fairly serious attempt to grapple with difficult issues, such as the ways that society tries (and fails) to deal with people who refuse to fit in. Which is an issue that quite a bit of the pulp crime fiction of this era tries to address.

Is it noir fiction? It definitely contains some noir fiction elements. And the ending has a nice noir kind of twist.

The plot works quite effectively, with the tension building as the two young punks get closer and closer to the edge of insanity. Mike and Johnny live in fantasy worlds of their own creation. They’re losers but they think they’re superior.

While Aarons tries to understand the motivations of juvenile delinquents he doesn’t fall for the temptation of sentimentalising them. Maybe it’s a tragedy that kids like this end up the way they do, but they’re still vicious thugs.

This book has been reissued in paperback in Stark House’s Black Gat Books imprint.

I’ve reviewed a couple of the author’s Sam Durell spy novels, Assignment…Suicide and Assignment - Karachi. They’re both worth reading if you’re a spy fiction fan.

Thursday, May 4, 2023

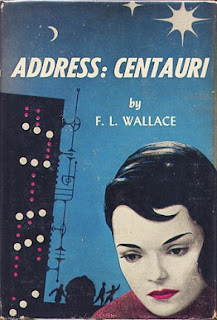

F.L. Wallace’s Address: Centauri

F.L. Wallace’s science fiction novel Address: Centauri was published in 1955. F.L. Wallace (1915-2004) was an American science fiction writer and that’s all that I know about him.

The story takes place in our solar system in a future in which interplanetary travel is commonplace but interstellar travel is not yet possible. Medical knowledge has advanced to the point where everybody is healthy and beautiful. Well, almost everybody. Everybody except for the Accidentals.

The Accidentals are people so grievously injured in accidents that the damage cannot be repaired. They can be kept alive but their bodies cannot be fixed. Some have no arms. Some have no legs. Some have no viable digestive system and must be kept alive with constant infusions of artificial nutrients.

Seeing the Accidentals would upset people so they’re hidden away on an asteroid. The asteroid is both hospital and prison.

There is one curious thing about the Accidentals - they’re incredibly long-lived. It’s an unexpected by product of the intense medical treatment they must receive. They live for centuries.

And that has given some of the Accidentals an idea. Interstellar travel is impossible because normal people don’t live log enough to survive such journeys. But that would be no problem for the Accidentals. They apply for permission to undertake an exploratory mission to the Centauri star system but their request is denied.

They decide to steal a spaceship and go anyway.

The ringleaders are Docchi (who has no arms), Jordan (who has no longs), Anti (a woman whose body just keeps growing to the point here she cannot support her own weight) and Nona. Nona is interesting. She looks like a normal girl. She cannot hear or speak. She appears to have almost no intelligence at all. She is however incredibly good with machines. She can make computers do things that nobody knew they could do. Docchi suspects that Nona’s problem is not that she lacks intelligence, but that she has a totally different kind of intelligence.

These four Accidentals try to set off for the Centauri system. That plan is foiled, but they have an alternative plan. Nona has figured out a way to make a gravity drive work. She could turn the whole asteroid into a spaceship. Which she proceeds to do.

The Accidentals head off into deep space, in search of a new world in which they will no longer be outcasts. But the authorities on Earth are pursuing them.

It’s a decent enough plot but it’s the Accidentals who make the story interesting. A major challenge for science fiction writers is to create alien races that are genuinely alien, rather than just humans with pointy ears. Wallace does something much more interesting. He creates human characters who are totally alien to the mainstream of humanity.

The most interesting character is Nona. She can neither speak nor hear, but that’s not what makes her alien. She has severe brain damage. It is assumed that she has almost no intelligence at all. Docchi however suspects that Nona is highly intelligent but that her brain has adapted to the damage and now works in a radically different way. She has the curiosity of a kitten, but when something interests her she can solve scientific and technical problems that baffle everyone else. She loves machines, and she knows how they think. She thinks the way they do.

Maureen, another Accidental, is interesting as well. She’s too female. Her hormones are out of control. Her instincts are female instincts, taken to an extreme degree. She has to be kept away from men. She cannot be trusted anywhere near a man.

The other Accidentals are more subtly different in a psychological sense, being forced to adapt to extraordinary physical disabilities.

The novel doesn’t precisely deal with posthumanism, at least not in the sense of humans being deliberately modified to become more than human. But, purely by coincidence, the Accidentals have developed the one attribute essential to interstellar travel - extreme longevity. On Earth they are regarded as very imperfect humans. In deep space they are in effect superior humans. So I guess the book does deal with posthumanism in an oblique way.

So apart from a fairly standard science fiction plot Address: Centauri has enough interesting elements to make it worth reading. Recommended.

The story takes place in our solar system in a future in which interplanetary travel is commonplace but interstellar travel is not yet possible. Medical knowledge has advanced to the point where everybody is healthy and beautiful. Well, almost everybody. Everybody except for the Accidentals.

The Accidentals are people so grievously injured in accidents that the damage cannot be repaired. They can be kept alive but their bodies cannot be fixed. Some have no arms. Some have no legs. Some have no viable digestive system and must be kept alive with constant infusions of artificial nutrients.

Seeing the Accidentals would upset people so they’re hidden away on an asteroid. The asteroid is both hospital and prison.

There is one curious thing about the Accidentals - they’re incredibly long-lived. It’s an unexpected by product of the intense medical treatment they must receive. They live for centuries.

And that has given some of the Accidentals an idea. Interstellar travel is impossible because normal people don’t live log enough to survive such journeys. But that would be no problem for the Accidentals. They apply for permission to undertake an exploratory mission to the Centauri star system but their request is denied.

They decide to steal a spaceship and go anyway.

The ringleaders are Docchi (who has no arms), Jordan (who has no longs), Anti (a woman whose body just keeps growing to the point here she cannot support her own weight) and Nona. Nona is interesting. She looks like a normal girl. She cannot hear or speak. She appears to have almost no intelligence at all. She is however incredibly good with machines. She can make computers do things that nobody knew they could do. Docchi suspects that Nona’s problem is not that she lacks intelligence, but that she has a totally different kind of intelligence.

These four Accidentals try to set off for the Centauri system. That plan is foiled, but they have an alternative plan. Nona has figured out a way to make a gravity drive work. She could turn the whole asteroid into a spaceship. Which she proceeds to do.

The Accidentals head off into deep space, in search of a new world in which they will no longer be outcasts. But the authorities on Earth are pursuing them.

It’s a decent enough plot but it’s the Accidentals who make the story interesting. A major challenge for science fiction writers is to create alien races that are genuinely alien, rather than just humans with pointy ears. Wallace does something much more interesting. He creates human characters who are totally alien to the mainstream of humanity.

The most interesting character is Nona. She can neither speak nor hear, but that’s not what makes her alien. She has severe brain damage. It is assumed that she has almost no intelligence at all. Docchi however suspects that Nona is highly intelligent but that her brain has adapted to the damage and now works in a radically different way. She has the curiosity of a kitten, but when something interests her she can solve scientific and technical problems that baffle everyone else. She loves machines, and she knows how they think. She thinks the way they do.

Maureen, another Accidental, is interesting as well. She’s too female. Her hormones are out of control. Her instincts are female instincts, taken to an extreme degree. She has to be kept away from men. She cannot be trusted anywhere near a man.

The other Accidentals are more subtly different in a psychological sense, being forced to adapt to extraordinary physical disabilities.

The novel doesn’t precisely deal with posthumanism, at least not in the sense of humans being deliberately modified to become more than human. But, purely by coincidence, the Accidentals have developed the one attribute essential to interstellar travel - extreme longevity. On Earth they are regarded as very imperfect humans. In deep space they are in effect superior humans. So I guess the book does deal with posthumanism in an oblique way.

Of course it also touches on other issues, such as the place of less-than-perfect humans in a world of perfect people.

Armchair Fiction have reissued this novel in a two-novel paperback edition, paired with If These Be Gods by Algis Budrys.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)