Assassin of Gor, published in 1970, is the fifth of John Norman’s Gor novels. The Gor series needs to be read in publication order so I’m going to be very careful not to hint at any spoilers for the earlier books.

Tarl Cabot is from Earth. He ends up on Gor, a hitherto unknown planet in out solar system. Gorean society is quite primitive. The technological level seems to be roughly equivalent to that of the classical world. There are no cars or aircraft or firearms or radio. But it’s actually more complicated than that. There is high technology on Gor. Very advanced technology indeed. But the Goreans do not have access to it

There are competing and often warring city-states. The Goreans are human but the animals are not those of the Earth. The animals include tarns - gigantic carnivorous birds that can be tamed (up to a point) and ridden. They constitute a kind of flying mediaeval heavy cavalry.

Tarl Cabot is in the city of Ar. He has gone there to kill a man, but he has another more important mission. He is accompanied by Elizabeth Caldwell, an Earth girl who appeared in an earlier Gor novel. Tarl and Elizabeth have to infiltrate themselves into the retinue of the current ruler of the city.

The situation in Ar is in reality not quite as it appears to Tarl and Elizabeth. They’re in more danger than they think. And they haven’t been quite as clever as they thought.

There will be lots of betrayals and lots of mayhem including an epic blood-drenched tarn race which is a bit like the chariot races in Ancient Rome but with gigantic flying birds.

John Norman (born John Frederick Lange Jr in 1931) is a philosophy professor. With the Gor novels he created a thrilling world of sword-and-planet adventure owing quite a bit to Edgar Rice Burroughs but he was also sneaking in various philosophical and cultural influences. Norman cited Homer, Freud, and Nietzsche as his major influences.

There’s more to these novels than there appears to be on the surface.

It is also very important not to be tempted into knee-jerk reactions by the controversial elements. It’s also important not to take these books at face value and jump to the conclusion that Norman was advocating the cultural practices he described. If you avoid those knee-jerk reactions it’s obvious that Tarl Cabot is very ambivalent indeed about Gorean culture.

One of the things Norman was trying to do was to create fictional societies that are genuinely alien. In this series there are two - the Goreans (who are human) and the Priest-Kings (who are very very non-human). Both societies are culturally very different from societies on Earth. He was intent on examining Gorean society in a great deal of detail. We get a huge amount of information about the taming of the tarns and their use in both sport and war. And having created culturally different fictional societies he was prepared to explore the ramifications of those cultural differences.

Which brings us to the slavery issue. In Gor female slavery is taken for granted. Of course in most human societies for most of human history slavery was taken for granted but on Gor the female slaves are unequivocally sex slaves. It’s the suggestion that some (not most, but some) are not entirely unhappy about the arrangement that shocks many people. Norman explains the workings of slavery on Gor in enormous detail. In this book Elizabeth has to play the role of Tarl’s slave. And he really does, to an extent, train her as a slave. They both enjoy it, and she certainly enjoys being tied up. But of course they are in fact playing a game.

Norman is exploring some of the sides of both masculinity and femininity that make people today so uncomfortable.

The Gor books are certainly provocative but sometimes we need provocative fiction. Assassin of Gor is highly recommended but you must read the earlier books first.

I’ve reviewed all the earlier books in this series - Tarnsman of Gor, Outlaw of Gor, Priest-Kings of Gor and Nomads of Gor.

pulp novels, trash fiction, detective stories, adventure tales, spy fiction, etc from the 19th century up to the 1970s

Showing posts with label fantasy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label fantasy. Show all posts

Monday, August 4, 2025

Sunday, November 3, 2024

John Norman’s Nomads of Gor

Nomads of Gor, published in 1969, is the fourth book in John Norman’s Gor series.

This series has aroused lots of controversy due to the fact that it depicts a society in which female slavery is practised. In fact there’s nothing controversial in the first three books. They’re imaginative and intelligent science fiction/fantasy novels with some fine world-building. This fourth book does start to get into more controversial territory. It’s worth reading in order to find out what the fuss was all about.

The premise of the series is that there is, within our solar system, a hitherto undiscovered planet. It is the Counter-Earth and is known as Gor. It is inhabited by humans, but the animal life is decidedly non-terrestrial. Gor is ruled by the mysterious priest-kings. Gor is technologically primitive, roughly equal to mediæval Europe. There is no electricity. There are no cars or locomotives. There are no firearms. As you find out as you make your way through the series the actual situation is much more complicated. Things are not as they seem to be.

Tarl Cabot is an ordinary American, from Earth. He has been transported to Gor by means that seem magical but are not. He has a destiny on Gor.

I’m not going to spoil things by revealing anything about the true situation. And I’m going to avoid spoilers for the earlier books.

It cannot be emphasised too strongly that the Gor books have to be read in publication order. If you don’t read them this way you’ll be very confused. At least in the early books there are ongoing story arcs.

While the Gor novels can be enjoyed as exciting sword-and-planet style adventures (there’s plenty of action) John Norman is a philosopher and he used the Gor novels to explore various philosophical, political, social and cultural speculations. And speculations about sexual mores. He created a complex fictional alternative world with beliefs and values that may seem strange but of course the beliefs and values of every human society at various stages of those societies’ histories always seem strange to those brought up in other societies and at other times.

You don’t have to approve of the Gorean society that Norman describes. He is clearly trying to be provocative and to challenge our assumptions. I like that in a writer.

In Nomads of Gor Tarl Cabot finds himself among the People of the Wagons, fierce nomadic tribesmen from the southern part of Gor. Their society is similar to mainstream Gorean society in some ways, and very different in others. There are four main nomad tribes. Relations between these tribes are often uneasy. If the omens are favourable an overall leader can be appointed, but the omens never are favourable.

Tarl is carrying out a mission on behalf of the priest-kings. His first step has to be to persuade these nomads not to kill him out of hand. He does that. They take a liking to him.

What he didn’t expect to find among the nomads was an American girl named Elizabeth Cardwell, a girl from 1960s New York City. Her presence just doesn’t make sense.

Tarl and Kamchak, one of the subordinate nomad leaders. His tribe is laying siege to the city of Turia. Tarl thinks the solution to his quest may be in Turia.

There’s another woman who plays a key role in this story. Aphris is Turian. Kamchak is determined to own her. The emotional and sexual dynamics involving Tarl, Kamchak, Aphris and Elizabeth are complex but crucial. The relationship between Tarl and Elizabeth is central to the story.

Tarl has conflicted views about Gorean sexual mores. He accepts that Gorean society is based on different values. He isn’t sure that he can fully accept those values, but he can see that they make a kind of sense. A major theme of Nomads of Gor is Tarl’s struggle with his conflicted views. Does he want Elizabeth as his slave? He doesn’t think so, but maybe he does. Does she want to be his slave? She doesn’t think so, but maybe she does. Norman is challenging us to think about social organisation and sexual mores and the extent to which they are built on a proper understanding of human motivations and the extent to which they are built on our own social prejudices. The reader will either enjoy being challenged in this way, or will be shocked and offended. But Norman does have serious intentions.

Nomads of Gor is a fine entry in the Gor saga and I highly recommend it but read the first three books first.

I’ve reviewed those first three Gor novels here - Tarnsman of Gor, Outlaw of Gor and Priest-Kings of Gor.

This series has aroused lots of controversy due to the fact that it depicts a society in which female slavery is practised. In fact there’s nothing controversial in the first three books. They’re imaginative and intelligent science fiction/fantasy novels with some fine world-building. This fourth book does start to get into more controversial territory. It’s worth reading in order to find out what the fuss was all about.

The premise of the series is that there is, within our solar system, a hitherto undiscovered planet. It is the Counter-Earth and is known as Gor. It is inhabited by humans, but the animal life is decidedly non-terrestrial. Gor is ruled by the mysterious priest-kings. Gor is technologically primitive, roughly equal to mediæval Europe. There is no electricity. There are no cars or locomotives. There are no firearms. As you find out as you make your way through the series the actual situation is much more complicated. Things are not as they seem to be.

Tarl Cabot is an ordinary American, from Earth. He has been transported to Gor by means that seem magical but are not. He has a destiny on Gor.

I’m not going to spoil things by revealing anything about the true situation. And I’m going to avoid spoilers for the earlier books.

It cannot be emphasised too strongly that the Gor books have to be read in publication order. If you don’t read them this way you’ll be very confused. At least in the early books there are ongoing story arcs.

While the Gor novels can be enjoyed as exciting sword-and-planet style adventures (there’s plenty of action) John Norman is a philosopher and he used the Gor novels to explore various philosophical, political, social and cultural speculations. And speculations about sexual mores. He created a complex fictional alternative world with beliefs and values that may seem strange but of course the beliefs and values of every human society at various stages of those societies’ histories always seem strange to those brought up in other societies and at other times.

You don’t have to approve of the Gorean society that Norman describes. He is clearly trying to be provocative and to challenge our assumptions. I like that in a writer.

In Nomads of Gor Tarl Cabot finds himself among the People of the Wagons, fierce nomadic tribesmen from the southern part of Gor. Their society is similar to mainstream Gorean society in some ways, and very different in others. There are four main nomad tribes. Relations between these tribes are often uneasy. If the omens are favourable an overall leader can be appointed, but the omens never are favourable.

Tarl is carrying out a mission on behalf of the priest-kings. His first step has to be to persuade these nomads not to kill him out of hand. He does that. They take a liking to him.

What he didn’t expect to find among the nomads was an American girl named Elizabeth Cardwell, a girl from 1960s New York City. Her presence just doesn’t make sense.

Tarl and Kamchak, one of the subordinate nomad leaders. His tribe is laying siege to the city of Turia. Tarl thinks the solution to his quest may be in Turia.

There’s another woman who plays a key role in this story. Aphris is Turian. Kamchak is determined to own her. The emotional and sexual dynamics involving Tarl, Kamchak, Aphris and Elizabeth are complex but crucial. The relationship between Tarl and Elizabeth is central to the story.

Tarl has conflicted views about Gorean sexual mores. He accepts that Gorean society is based on different values. He isn’t sure that he can fully accept those values, but he can see that they make a kind of sense. A major theme of Nomads of Gor is Tarl’s struggle with his conflicted views. Does he want Elizabeth as his slave? He doesn’t think so, but maybe he does. Does she want to be his slave? She doesn’t think so, but maybe she does. Norman is challenging us to think about social organisation and sexual mores and the extent to which they are built on a proper understanding of human motivations and the extent to which they are built on our own social prejudices. The reader will either enjoy being challenged in this way, or will be shocked and offended. But Norman does have serious intentions.

Nomads of Gor is a fine entry in the Gor saga and I highly recommend it but read the first three books first.

I’ve reviewed those first three Gor novels here - Tarnsman of Gor, Outlaw of Gor and Priest-Kings of Gor.

Saturday, September 21, 2024

Victor Rousseau's Eric of the Strong Heart

Victor Rousseau (1879-1960) was an English British writer who wrote science fiction and other assorted pulp fiction works.

His lost world novel Eric of the Strong Heart was serialised in four parts in Railroad Man's Magazine in November and December 1918.

Eric Silverstein is what would later be called a geek. He lives in New York, he’s wealthy and he’s a history buff. Everything changes for him when he cores across a sideshow attraction featuring a mysterious princess from an exotic land. Much to the amusement of the crowd she speaks in gibberish. Eric notices two things. Firstly her costume is Saxon from around a thousand years earlier and it’s totally authentic. Secondly she isn’t speaking gibberish - she is speaking Old English. Being a history fanatic Eric understands the language. The princess (whose name is Editha) is very indignant. She was expecting an audience with the king of this land.

There is a disturbance and the princess, aided by Eric, makes her escape. She just wants to return to her longship. It turns out she really does have a longship. Then something very odd happens - the princess suddenly becomes a knife-wielding maniac. Her two attendants make apologies for her and it is suggested that it would be safer for Eric to forget all about her. Editha sails off, to return to her own land.

Eric cannot forget her. Oddly enough, even though she is very beautiful, he does not have fantasies of marrying her. He thinks his friend Ralph would be a perfect husband for her.

Eric is intelligent but he has a few huge blind spots. He also underestimates himself. He has never been handsome or athletic. He does not see himself as the stuff that heroes are made of, while he thinks of Ralph as being very much hero material.

Eric knows his history and his geography. He thinks he knows where Editha’s land is. It is in the frozen Arctic, north of Spitzbergen. He buys himself a yacht and with two companions sets off to find Editha’s homeland. His two companions are Ralph and a fisherman named Bjorn.

This is a classic lost world story. Editha’s land has been cut off from the rest of humanity for a millennium. People there live as they did a thousand years ago. There are in fact two peoples there, one (the rulers) descended from the Dames and one (the slaves) descended from the Angles. There are two kings, but the Danish king rules. Editha is the daughter of the Anglian king.

In fact there are three people on this remote island, the third being a race of Trolls.

There are of course power struggles. The Angles have never been entirely reconciled to their subordinate status. The Danes are determined to maintain their superior position. Having two kings complicates things. There has been intermarriage. There are conspiracies aplenty. The arrival of outsiders increases the tension levels, especially when one of the outsiders puts himself forward as a candidate for the kingship.

There is also a sword with a legend attached to it. The man who draws the sword out of its rocky scabbard will be king.

There are conflicted loyalties and betrayals, not just among the islanders but among the three outsiders as well. Bjorn seem to have his own agenda.

There are people who feel they are chosen by destiny, and they can be thereby tempted to do desperate things.

This is a complex lost world. The story offers a lot of action and adventure but with some psychological twists. Eric is a man who is intelligent and resourceful but he has made a very serious error of judgment which could have momentous consequences. There is magic, although the exact nature of the magic is ambiguous.

The ending holds a few surprises.

This is an above-average lost world tale and it’s highly recommended.

His lost world novel Eric of the Strong Heart was serialised in four parts in Railroad Man's Magazine in November and December 1918.

Eric Silverstein is what would later be called a geek. He lives in New York, he’s wealthy and he’s a history buff. Everything changes for him when he cores across a sideshow attraction featuring a mysterious princess from an exotic land. Much to the amusement of the crowd she speaks in gibberish. Eric notices two things. Firstly her costume is Saxon from around a thousand years earlier and it’s totally authentic. Secondly she isn’t speaking gibberish - she is speaking Old English. Being a history fanatic Eric understands the language. The princess (whose name is Editha) is very indignant. She was expecting an audience with the king of this land.

There is a disturbance and the princess, aided by Eric, makes her escape. She just wants to return to her longship. It turns out she really does have a longship. Then something very odd happens - the princess suddenly becomes a knife-wielding maniac. Her two attendants make apologies for her and it is suggested that it would be safer for Eric to forget all about her. Editha sails off, to return to her own land.

Eric cannot forget her. Oddly enough, even though she is very beautiful, he does not have fantasies of marrying her. He thinks his friend Ralph would be a perfect husband for her.

Eric is intelligent but he has a few huge blind spots. He also underestimates himself. He has never been handsome or athletic. He does not see himself as the stuff that heroes are made of, while he thinks of Ralph as being very much hero material.

Eric knows his history and his geography. He thinks he knows where Editha’s land is. It is in the frozen Arctic, north of Spitzbergen. He buys himself a yacht and with two companions sets off to find Editha’s homeland. His two companions are Ralph and a fisherman named Bjorn.

This is a classic lost world story. Editha’s land has been cut off from the rest of humanity for a millennium. People there live as they did a thousand years ago. There are in fact two peoples there, one (the rulers) descended from the Dames and one (the slaves) descended from the Angles. There are two kings, but the Danish king rules. Editha is the daughter of the Anglian king.

In fact there are three people on this remote island, the third being a race of Trolls.

There are of course power struggles. The Angles have never been entirely reconciled to their subordinate status. The Danes are determined to maintain their superior position. Having two kings complicates things. There has been intermarriage. There are conspiracies aplenty. The arrival of outsiders increases the tension levels, especially when one of the outsiders puts himself forward as a candidate for the kingship.

There is also a sword with a legend attached to it. The man who draws the sword out of its rocky scabbard will be king.

There are conflicted loyalties and betrayals, not just among the islanders but among the three outsiders as well. Bjorn seem to have his own agenda.

There are people who feel they are chosen by destiny, and they can be thereby tempted to do desperate things.

This is a complex lost world. The story offers a lot of action and adventure but with some psychological twists. Eric is a man who is intelligent and resourceful but he has made a very serious error of judgment which could have momentous consequences. There is magic, although the exact nature of the magic is ambiguous.

The ending holds a few surprises.

This is an above-average lost world tale and it’s highly recommended.

Thursday, August 1, 2024

Berkeley Livingston’s Queen of the Panther World

Berkeley Livingston’s science fiction novel Queen of the Panther World was published in Fantastic Adventures in July 1948.

It starts with a guy named Berkeley Livingston (yes the author has made himself a character in the book) visiting the zoo with his buddy Hank. They’re looking at the panthers. One of the panthers is much bigger than the others and seems different somehow. Hank has the crazy idea that the panther is communicating with him.

There’s a woman named Luria and Hank thinks she can communicate with him by some sort of telepathy. Luria decides to take Hank on a journey and Berk agrees to tag along. She’s going to take them to her world. Berk naturally thinks it’s all crazy talk, until suddenly the three of them are not in Chicago any more. They’re on a strange planet and there are giant lizard-like creatures with human riders.

The idea of transporting a story’s hero to another planet by simply hand-waving it away as “mind over matter” had already been used many times. It’s not a satisfying solution if you’re trying to write hard science fiction but if you’re writing what is essentially a fantasy novel it’s an acceptable technique and at least you don’t have to bother with a lot of unconvincing techno-babble. It’s basically magic but it does the job.

This strange planet is very strange indeed. The sun never sets. There are other odd things about it. Everybody falls asleep at exactly the same moment.

Luria’s society is a society run by women. The men do the housework and obey orders. The problem is that there’s a villain named Loko planning to establish his rule over the whole planet by force. While Luria’s amazons are brave enough she’s not convinced that they can stand up to Loko’s army. The men of Luria’s tribe are passive and helpless but they will have to be persuaded to fight against Loko. Things will have to change. The men will have to regain their self-respect. In reality you’d expect such a social revolution to be difficult to achieve but in this book it just happens overnight because the plot demands it.

Berk and Hank have various narrow escapes from danger. They get captured by Loko’s minions, as does Luria. There are various battles between the opposing forces. It’s all basic fantasy adventure stuff.

There’s also a bird. A parrot. But he’s no ordinary parrot.

Naturally Hank and Luria fall in love, and Berk falls in love with one of Luri’s amazon warriors.

Although we’re told that the inhabitants of this planet once had advanced technology this novel does not really qualify as a sword-and-planet story. It just doesn’t have quite the right feel, even though there are obvious Edgar Rice Burroughs influences. It doesn’t quite have a sword-and-sorcery feel either.

The tone is something of a problem. At times it seems to be veering towards a tongue-in-cheek approach but it lacks the lightness of touch needed to pull it off, and at other times it seems to be playing things rather straight.

It all seems like a rehashing of ideas culled from better stories by better writers. The world-building is not overly impressive. The interestingly strange things about this world are never explored in depth or explained in any way.

The social and psychological implications of a society having to undergo a total social revolution are not explored at all.

There’s also a lack of any emotional depth. We feel that the romances between the two heroes and their amazon girlfriends are necessary for the plot so they just happen without any real emotional tension ever being developed.

This is the kind of story that I usually enjoy but in this case it’s not handled well and the book is rather shoddily written. It all falls rather flat. I really cannot recommend this novel.

This novella has been paired with Jack Williamson’s truly excellent novella Hocus-Pocus Universe in an Armchair Fiction two-novel paperback edition. Hocus-Pocus Universe is so good that the paperback is worth buying for that reason alone.

It starts with a guy named Berkeley Livingston (yes the author has made himself a character in the book) visiting the zoo with his buddy Hank. They’re looking at the panthers. One of the panthers is much bigger than the others and seems different somehow. Hank has the crazy idea that the panther is communicating with him.

There’s a woman named Luria and Hank thinks she can communicate with him by some sort of telepathy. Luria decides to take Hank on a journey and Berk agrees to tag along. She’s going to take them to her world. Berk naturally thinks it’s all crazy talk, until suddenly the three of them are not in Chicago any more. They’re on a strange planet and there are giant lizard-like creatures with human riders.

The idea of transporting a story’s hero to another planet by simply hand-waving it away as “mind over matter” had already been used many times. It’s not a satisfying solution if you’re trying to write hard science fiction but if you’re writing what is essentially a fantasy novel it’s an acceptable technique and at least you don’t have to bother with a lot of unconvincing techno-babble. It’s basically magic but it does the job.

This strange planet is very strange indeed. The sun never sets. There are other odd things about it. Everybody falls asleep at exactly the same moment.

Luria’s society is a society run by women. The men do the housework and obey orders. The problem is that there’s a villain named Loko planning to establish his rule over the whole planet by force. While Luria’s amazons are brave enough she’s not convinced that they can stand up to Loko’s army. The men of Luria’s tribe are passive and helpless but they will have to be persuaded to fight against Loko. Things will have to change. The men will have to regain their self-respect. In reality you’d expect such a social revolution to be difficult to achieve but in this book it just happens overnight because the plot demands it.

Berk and Hank have various narrow escapes from danger. They get captured by Loko’s minions, as does Luria. There are various battles between the opposing forces. It’s all basic fantasy adventure stuff.

There’s also a bird. A parrot. But he’s no ordinary parrot.

Naturally Hank and Luria fall in love, and Berk falls in love with one of Luri’s amazon warriors.

Although we’re told that the inhabitants of this planet once had advanced technology this novel does not really qualify as a sword-and-planet story. It just doesn’t have quite the right feel, even though there are obvious Edgar Rice Burroughs influences. It doesn’t quite have a sword-and-sorcery feel either.

The tone is something of a problem. At times it seems to be veering towards a tongue-in-cheek approach but it lacks the lightness of touch needed to pull it off, and at other times it seems to be playing things rather straight.

It all seems like a rehashing of ideas culled from better stories by better writers. The world-building is not overly impressive. The interestingly strange things about this world are never explored in depth or explained in any way.

The social and psychological implications of a society having to undergo a total social revolution are not explored at all.

There’s also a lack of any emotional depth. We feel that the romances between the two heroes and their amazon girlfriends are necessary for the plot so they just happen without any real emotional tension ever being developed.

This is the kind of story that I usually enjoy but in this case it’s not handled well and the book is rather shoddily written. It all falls rather flat. I really cannot recommend this novel.

This novella has been paired with Jack Williamson’s truly excellent novella Hocus-Pocus Universe in an Armchair Fiction two-novel paperback edition. Hocus-Pocus Universe is so good that the paperback is worth buying for that reason alone.

Saturday, August 26, 2023

Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle (Dream Story)

Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 short novel (more a novella really) Traumnovelle, also known as Dream Story or Rhapsody, was the basis for Stanley Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut.

Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931) was a successful although controversial Viennese writer. He wrote many plays and short stories as well as two novels. He can be considered to be both a Modernist and a Decadent. He qualified as a doctor and practised medicine before turning to writing full-time.

Traumnovelle was published in 1926 and although no time period is specified it clearly takes place before the First World War, in the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The hero fought several duels during his student days and it is clear that duelling is still reasonably common. There is very much an atmosphere of fin de siècle decadence.

Fridolin is a 35-year-old Viennese doctor, happily married to Albertine. They have a six-year-old daughter. After a masked ball Fridolin and Albertine discuss sexual temptations that they have experienced. Albertine tells her husband of a young Dane with whom she was tempted to have an affair. This disturbs Fridolin more than he expected.

Fridolin has a slightly unsettling encounter with the daughter of a patient who has just died. The woman, Marianne, tells Fridolin that she is love with him. Fridolin beats a hasty retreat.

Fridolin then has an encounter with a young prostitute but the fear of syphilis prevents him from doing anything.

He doesn’t want to return home. He walks the streets until dark. He runs into Nachtigall, an old acquaintance from his medical school days. Nachtigall is now a slightly disreputable piano-player. Nachtigall tells Fridolin of an odd piano-playing job he has to go to that evening. It involves playing the piano at what might be private house parties, or secret meeting, or orgies. He really doesn’t know what goes on at these parties since he is blindfolded, and he has no idea where the parties take place although he’s fairly sure the locations are a number of country houses. All he knows is that he is blindfolded and taken somewhere in a coach. Fridolin is fascinated and wants to go as well. A password is required, which Nachtigall may be able to provide.

But first Fridolin must get hold of a costume and a mask - everyone at these meetings wears masks. While obtaining the mask he has another odd experience, involving two men dressed as judges and a young girl.

Fridolin manages to attend one of the secret meetings. The men dress as monks, the women as nuns. But the women soon shed their nuns’ habits. Fridolin has no idea if he is witnessing a commonplace orgy or a religious ritual or a meeting of a bizarre esoteric or even political cult. What happens to Fridolin at this strange house party, and what happens to one of the women who tries to warn him off, leaves him bewildered.

His attempts to contact Nachtigall again, and to learn the fate of the woman at the house party orgy who tried to save him, leave him even more bewildered.

If you’ve seen Kubrick’s movie it will be obvious from what I’ve said so far that it’s a remarkably faithful adaptation of the novel. Most of the incidents of the movie are taken directly from the novel. There’s also the same sense of a blurring of the line between reality and fantasy. There is no way to be sure which events really happen and which are dreams or fantasies or illusions. Everything might be real. Everything might be a dream. Or the events might be a mixture of dream and reality.

There’s the same sense of decadence and forbidden pleasures and the same sense that what is happening might be sinister, or it might be just a rather wild party.

Even the conspiracy theory angle which fascinates so many viewers of the movie is there, although it is given much greater prominence in the movie. Secret societies, whether political or religious or occult, were not exactly unknown in period leading up to the First World War. No-one was really certain how many such societies actually existed, but plenty of people believed in their existence. And some almost certainly did exist. There were real conspiracies in that age.

There are some differences between novel and film. In the novel Albertine has a dream which becomes pivotal. Fridolin seems to regard her dream as being more real than his real-life adventure, and given that we have our doubts about the reality of his adventure perhaps it is more real. As in the movie there is also the possibility that Fridolin’s adventure is real, but that he has misinterpreted its meaning. In fact he has no clear idea at all of the significance of the events at that mysterious country house.

As in the movie the real question is whether Fridolin’s marriage can survive such a series of revelations and adventures, real or imaginary. Has Fridolin betrayed Albertine? Has she betrayed him?

There are obvious Freudian influences (and Freud and Schnitzler admired each other’s work). Whether Fridolin’s adventures are real or just dreams doesn’t matter, since dreams are more significant than conscious thoughts. Schnitzler was linked to the literary avant-garde and had a great interest in literary explorations of both the conscious and unconscious mind. He was one of the pioneers of stream-of-consciousness fiction.

Traumnovelle is a fascinating novella. If you’re a fan of Eyes Wide Shut or of decadent fiction it’s a must-read. Highly recommended. The English translation has been published by Penguin.

Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931) was a successful although controversial Viennese writer. He wrote many plays and short stories as well as two novels. He can be considered to be both a Modernist and a Decadent. He qualified as a doctor and practised medicine before turning to writing full-time.

Traumnovelle was published in 1926 and although no time period is specified it clearly takes place before the First World War, in the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The hero fought several duels during his student days and it is clear that duelling is still reasonably common. There is very much an atmosphere of fin de siècle decadence.

Fridolin is a 35-year-old Viennese doctor, happily married to Albertine. They have a six-year-old daughter. After a masked ball Fridolin and Albertine discuss sexual temptations that they have experienced. Albertine tells her husband of a young Dane with whom she was tempted to have an affair. This disturbs Fridolin more than he expected.

Fridolin has a slightly unsettling encounter with the daughter of a patient who has just died. The woman, Marianne, tells Fridolin that she is love with him. Fridolin beats a hasty retreat.

Fridolin then has an encounter with a young prostitute but the fear of syphilis prevents him from doing anything.

He doesn’t want to return home. He walks the streets until dark. He runs into Nachtigall, an old acquaintance from his medical school days. Nachtigall is now a slightly disreputable piano-player. Nachtigall tells Fridolin of an odd piano-playing job he has to go to that evening. It involves playing the piano at what might be private house parties, or secret meeting, or orgies. He really doesn’t know what goes on at these parties since he is blindfolded, and he has no idea where the parties take place although he’s fairly sure the locations are a number of country houses. All he knows is that he is blindfolded and taken somewhere in a coach. Fridolin is fascinated and wants to go as well. A password is required, which Nachtigall may be able to provide.

But first Fridolin must get hold of a costume and a mask - everyone at these meetings wears masks. While obtaining the mask he has another odd experience, involving two men dressed as judges and a young girl.

Fridolin manages to attend one of the secret meetings. The men dress as monks, the women as nuns. But the women soon shed their nuns’ habits. Fridolin has no idea if he is witnessing a commonplace orgy or a religious ritual or a meeting of a bizarre esoteric or even political cult. What happens to Fridolin at this strange house party, and what happens to one of the women who tries to warn him off, leaves him bewildered.

His attempts to contact Nachtigall again, and to learn the fate of the woman at the house party orgy who tried to save him, leave him even more bewildered.

If you’ve seen Kubrick’s movie it will be obvious from what I’ve said so far that it’s a remarkably faithful adaptation of the novel. Most of the incidents of the movie are taken directly from the novel. There’s also the same sense of a blurring of the line between reality and fantasy. There is no way to be sure which events really happen and which are dreams or fantasies or illusions. Everything might be real. Everything might be a dream. Or the events might be a mixture of dream and reality.

There’s the same sense of decadence and forbidden pleasures and the same sense that what is happening might be sinister, or it might be just a rather wild party.

Even the conspiracy theory angle which fascinates so many viewers of the movie is there, although it is given much greater prominence in the movie. Secret societies, whether political or religious or occult, were not exactly unknown in period leading up to the First World War. No-one was really certain how many such societies actually existed, but plenty of people believed in their existence. And some almost certainly did exist. There were real conspiracies in that age.

There are some differences between novel and film. In the novel Albertine has a dream which becomes pivotal. Fridolin seems to regard her dream as being more real than his real-life adventure, and given that we have our doubts about the reality of his adventure perhaps it is more real. As in the movie there is also the possibility that Fridolin’s adventure is real, but that he has misinterpreted its meaning. In fact he has no clear idea at all of the significance of the events at that mysterious country house.

As in the movie the real question is whether Fridolin’s marriage can survive such a series of revelations and adventures, real or imaginary. Has Fridolin betrayed Albertine? Has she betrayed him?

There are obvious Freudian influences (and Freud and Schnitzler admired each other’s work). Whether Fridolin’s adventures are real or just dreams doesn’t matter, since dreams are more significant than conscious thoughts. Schnitzler was linked to the literary avant-garde and had a great interest in literary explorations of both the conscious and unconscious mind. He was one of the pioneers of stream-of-consciousness fiction.

Traumnovelle is a fascinating novella. If you’re a fan of Eyes Wide Shut or of decadent fiction it’s a must-read. Highly recommended. The English translation has been published by Penguin.

Sunday, July 23, 2023

S.P. Meek's The Drums of Tapajos

The Drums of Tapajos was serialised in the pulp magazine Amazing Stories in December 1930 and January 1931. All I know about the author, S.P. Meek (1894-1972) is that he was American and had served in the military in the First World War, and that he was for a brief period quite prolific.

This novel has been re-issued in paperback by Armchair Fiction in their excellent Lost World-Lost Race series.

The book begins with three American servicemen who joined up too late to see action in the First World War. Action is what they now want. They’re bored by the peacetime army. They consider heading to South America in the hope of getting mixed up in a revolution. Thy have no political beliefs, but a revolution sounds like it might be exciting. Then Willis, a friend of theirs, tells them an odd story about an adventure he had in the wilds of Brazil. A strange old man suddenly appeared and gave him a knife and a map, and then promptly died. Willis lost the map but he thinks he remembers the main details.

The knife is interesting - very very old indeed. Willis has had the blade analysed but no-one can identify the allow from which it was made. Willis suggests that the four of them set off into the Amazon rainforest to find the source of that knife. They may not find anything worthwhile but it will be a grand adventure, and there’s always the slim chance of finding treasure. That knife was clearly manufactured by an advanced civilisation, and that certainly suggests the possibility of finding the ruins of a lost civilisation. And where there are ruins there may be treasure.

They set off down the Rio Tapajos. The locals warn them that they are headed into forbidden territory. If they hear the drums their fate is sealed.

The journey down the river provides plenty of danger and excitement - alligators, tribesmen shooting poisoned arrows at them, strange bloodcurdling screams from the forest, and tracks that are hard to interpret as being the tracks of any living animals.

Of course they do find a city, but it’s no ruin. The city of Troyana is run by people who appear to be Freemasons, of a sort. Or perhaps they follow a system that was to some extent the origin of Freemasonry. The city has been there for six thousand years.

It’s not Atlantis, but some of the inhabitants were originally from Atlantis.

It’s a utopia of sorts. Perhaps you could call it a flawed utopia. It has a definite dark side.

They are welcomed by a guy named Nahum. He happens to have three very beautiful granddaughters, a fact of keen interest to the young Americans.

Are the four Americans prisoners or guests? They’re not certain. Do the rulers of Troyana have friendly or unfriendly intentions? That is also uncertain.

For the scientifically inclined narrator, Lieutenant Duncan, there is much of interest. We get a certain amount of technobabble, reflecting the technological obsessions of 1930 - radio, a kind of television, unlocking the power of the atom. The city is largely automated, but there is an underclass who may no slaves but they certainly appear to live in conditions of forced servitude. Those who rule the city are enlightened, in some ways.

The Americans witness a religious ritual which reminds them of rituals of the ancient world, and that ritual is where the trouble starts.

It’s an entertaining story with some decent world-building. Perhaps some of the action scenes could have been a bit more exciting.

The most interesting aspect of the novel is a certain ambiguity in the way this lost city is described, and in the view of the young adventurers towards this lost civilisation. And some ambiguity on the part of the city-dwellers towards these outsiders. There’s also some ambiguity about the intentions of our four heroes. Do they seek merely to enrich themselves?

The ending leaves some questions unanswered. It suggests that Meek was keeping his options open in case he decided to write a sequel, and in fact in 1932 he did just that. It’s called Troyana and if I ever come across a copy I’ll probably pick it up.

The Drums of Tapajos isn’t one of the great lost civilisation tales but it’s a solid adventure. Recommended, especially if (like me) you just can’t get enough of the lost world genre.

This novel has been re-issued in paperback by Armchair Fiction in their excellent Lost World-Lost Race series.

The book begins with three American servicemen who joined up too late to see action in the First World War. Action is what they now want. They’re bored by the peacetime army. They consider heading to South America in the hope of getting mixed up in a revolution. Thy have no political beliefs, but a revolution sounds like it might be exciting. Then Willis, a friend of theirs, tells them an odd story about an adventure he had in the wilds of Brazil. A strange old man suddenly appeared and gave him a knife and a map, and then promptly died. Willis lost the map but he thinks he remembers the main details.

The knife is interesting - very very old indeed. Willis has had the blade analysed but no-one can identify the allow from which it was made. Willis suggests that the four of them set off into the Amazon rainforest to find the source of that knife. They may not find anything worthwhile but it will be a grand adventure, and there’s always the slim chance of finding treasure. That knife was clearly manufactured by an advanced civilisation, and that certainly suggests the possibility of finding the ruins of a lost civilisation. And where there are ruins there may be treasure.

They set off down the Rio Tapajos. The locals warn them that they are headed into forbidden territory. If they hear the drums their fate is sealed.

The journey down the river provides plenty of danger and excitement - alligators, tribesmen shooting poisoned arrows at them, strange bloodcurdling screams from the forest, and tracks that are hard to interpret as being the tracks of any living animals.

Of course they do find a city, but it’s no ruin. The city of Troyana is run by people who appear to be Freemasons, of a sort. Or perhaps they follow a system that was to some extent the origin of Freemasonry. The city has been there for six thousand years.

It’s not Atlantis, but some of the inhabitants were originally from Atlantis.

It’s a utopia of sorts. Perhaps you could call it a flawed utopia. It has a definite dark side.

They are welcomed by a guy named Nahum. He happens to have three very beautiful granddaughters, a fact of keen interest to the young Americans.

Are the four Americans prisoners or guests? They’re not certain. Do the rulers of Troyana have friendly or unfriendly intentions? That is also uncertain.

For the scientifically inclined narrator, Lieutenant Duncan, there is much of interest. We get a certain amount of technobabble, reflecting the technological obsessions of 1930 - radio, a kind of television, unlocking the power of the atom. The city is largely automated, but there is an underclass who may no slaves but they certainly appear to live in conditions of forced servitude. Those who rule the city are enlightened, in some ways.

The Americans witness a religious ritual which reminds them of rituals of the ancient world, and that ritual is where the trouble starts.

It’s an entertaining story with some decent world-building. Perhaps some of the action scenes could have been a bit more exciting.

The most interesting aspect of the novel is a certain ambiguity in the way this lost city is described, and in the view of the young adventurers towards this lost civilisation. And some ambiguity on the part of the city-dwellers towards these outsiders. There’s also some ambiguity about the intentions of our four heroes. Do they seek merely to enrich themselves?

The ending leaves some questions unanswered. It suggests that Meek was keeping his options open in case he decided to write a sequel, and in fact in 1932 he did just that. It’s called Troyana and if I ever come across a copy I’ll probably pick it up.

The Drums of Tapajos isn’t one of the great lost civilisation tales but it’s a solid adventure. Recommended, especially if (like me) you just can’t get enough of the lost world genre.

Tuesday, June 6, 2023

Lester Del Rey’s When the World Tottered

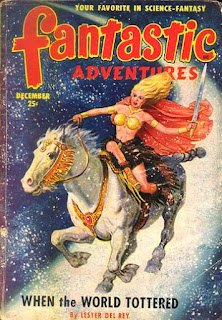

Lester Del Rey’s 1950 novel When the World Tottered, published in Fantastic Adventures in December 1950, is one of many attempts to combine ancient mythology with science fiction.

Lester Del Rey (1915-1993) was a fairly prolific American science fiction writer.

The novel begins at un unspecified time but probably a few years into the future. Leif Svensen is a farmer living in the United States. He is of Scandinavian descent, which is important. The world is undergoing some sort of crisis. Particularly harsh winters, crop failures, food shortages. Things are growing rather tense. And people have reported seeing women riding through the air on horseback, which Leif attributes to hysteria.

Leif is involved in a dispute with his neighbours over his dog Lobo which has been accused of killing livestock. Things come to a head, there is an attempt to Lynch Leif and his twin brother Lee, an attempt which ends in a violent fight. Leif remembers being struck a savage blow.

Leif wakes up to discover that he is no longer on Earth. He is in Asgard, the home of the Norse gods. He was brought there by a Valkyrie. The task of the Valkyries of course is to carry heroes killed in combat to Asgard. It seems that Leif is such a fallen hero.

That’s disturbing enough, but it’s worse than that. The time for Ragnarok is approaching. All will be destroyed, including the gods themselves. It is their inescapable destiny.

Leif has his doubts about that. He comes to the conclusion that these gods among whom he now finds himself really were the origins of Norse mythology, but he suspects that they are simply beings from another dimension, one of several such alternate dimensions. They really are gods, the giants with whom the gods will do battle really do exist, but Leif is not convinced that their destiny is written in stone. Maybe he can change it. It might help if the gods had better weaponry. Spears and swords and battle-axes and Thor’s hammer all very well, but grenades might give the gods more of an edge.

Of course the odds would be even better if he had some Uranium-235 but there’s no chance of that. Until one of the dwarf smiths who serves the gods informs him that he can create an almost limitless supply of that element.

Loki, the notorious trickster god, also has doubts about the inevitability of fate. He also has plans to change the destiny of the gods. Maybe he and Leif can come up with a plan. Naturally a lot depends on whether Leif can trust Loki.

There’s another complication for Leif. He has fallen in love with a pretty Valkyrie, Fulla.

This novel seems on the surface to be fantasy but really it’s science fiction. Asgard is simply another dimension in which the rules are different. It just happens to be a dimension in which certain things are possible which would be considered magic on Earth. These gods are immortal beings but whether they are gods or not is an open question.

There’s no shortage of action. Leif is trapped in the world of the frost giants and must battle his way to freedom. Ragnarok is to involve a mighty battle, and that’s what happens. It’s a bloody battle indeed. The gods believe they will lose, because Fate has decreed that they will lose. Leif intends to win the battle.

There’s plenty here to please fans of action and mayhem, and plenty to please science fiction fans who want imaginative speculation about other worlds.

It’s all very entertaining. Highly recomended.

Armchair Fiction have reissued this one in one of their two-novel paperback editions, paired with Ice City of the Gorgon by Richard S. Shaver and Chester S. Geier (a book that deals with a somewhat similar theme).

I’ve also reviewed Lester Del Rey’s Pursuit, a very different kind of science fiction novel but a very good one.

Lester Del Rey (1915-1993) was a fairly prolific American science fiction writer.

The novel begins at un unspecified time but probably a few years into the future. Leif Svensen is a farmer living in the United States. He is of Scandinavian descent, which is important. The world is undergoing some sort of crisis. Particularly harsh winters, crop failures, food shortages. Things are growing rather tense. And people have reported seeing women riding through the air on horseback, which Leif attributes to hysteria.

Leif is involved in a dispute with his neighbours over his dog Lobo which has been accused of killing livestock. Things come to a head, there is an attempt to Lynch Leif and his twin brother Lee, an attempt which ends in a violent fight. Leif remembers being struck a savage blow.

Leif wakes up to discover that he is no longer on Earth. He is in Asgard, the home of the Norse gods. He was brought there by a Valkyrie. The task of the Valkyries of course is to carry heroes killed in combat to Asgard. It seems that Leif is such a fallen hero.

That’s disturbing enough, but it’s worse than that. The time for Ragnarok is approaching. All will be destroyed, including the gods themselves. It is their inescapable destiny.

Leif has his doubts about that. He comes to the conclusion that these gods among whom he now finds himself really were the origins of Norse mythology, but he suspects that they are simply beings from another dimension, one of several such alternate dimensions. They really are gods, the giants with whom the gods will do battle really do exist, but Leif is not convinced that their destiny is written in stone. Maybe he can change it. It might help if the gods had better weaponry. Spears and swords and battle-axes and Thor’s hammer all very well, but grenades might give the gods more of an edge.

Of course the odds would be even better if he had some Uranium-235 but there’s no chance of that. Until one of the dwarf smiths who serves the gods informs him that he can create an almost limitless supply of that element.

Loki, the notorious trickster god, also has doubts about the inevitability of fate. He also has plans to change the destiny of the gods. Maybe he and Leif can come up with a plan. Naturally a lot depends on whether Leif can trust Loki.

There’s another complication for Leif. He has fallen in love with a pretty Valkyrie, Fulla.

This novel seems on the surface to be fantasy but really it’s science fiction. Asgard is simply another dimension in which the rules are different. It just happens to be a dimension in which certain things are possible which would be considered magic on Earth. These gods are immortal beings but whether they are gods or not is an open question.

There’s no shortage of action. Leif is trapped in the world of the frost giants and must battle his way to freedom. Ragnarok is to involve a mighty battle, and that’s what happens. It’s a bloody battle indeed. The gods believe they will lose, because Fate has decreed that they will lose. Leif intends to win the battle.

There’s plenty here to please fans of action and mayhem, and plenty to please science fiction fans who want imaginative speculation about other worlds.

It’s all very entertaining. Highly recomended.

Armchair Fiction have reissued this one in one of their two-novel paperback editions, paired with Ice City of the Gorgon by Richard S. Shaver and Chester S. Geier (a book that deals with a somewhat similar theme).

I’ve also reviewed Lester Del Rey’s Pursuit, a very different kind of science fiction novel but a very good one.

Thursday, May 11, 2023

Clark Ashton Smith's Hyperborea stories

I’ve been a fan of the work of Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961) for years. Smith was a member of Lovecraft’s circle and he’s notable for the extreme ornateness of his prose. Smith’s Hyperborea cycle shows Lovecraft’s influence very strongly and it has definite links to Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos.

Hyperborea is a mythical world with some similarities to Robert E. Howard’s Hyboria. Hyperborea is a world of wizardry and lost prehistoric civilisations.

In The Tale of Satampra Zeiros two thieves set out to loot the treasures of the lost city of Commoriom, a city shunned by all. The thieves soon find out exactly why everybody shuns the ruined city. The city might be dead but the old gods that had been been worshipped there might not be entirely dead. And they are rather savage gods. There’s more excitement than is usual in a Smith story, there’s a superbly evoked atmosphere of decay and malevolence and there are some definite touches of black humour.

The Door to Saturn is literally about a door to Saturn. The sorcerer Eibon is facing charges of heresy and makes his escape from the enraged inquisitor Morghi just in time. Eibon is a devotee of the god Zhothaqquagh and that deity has provided the sorcerer with a very convenient little door that opens on the surface of the planet Saturn. The only downside is, it he uses the door it will be a one-way trip.

Morghi somewhat unwisely follows Eibon through the door. They find that Saturn is a profoundly strange place. It’s not particularly dangerous, just strange.

This is very much a tongue-in-cheek story with a number of elaborate jokes. There’s no real terror and there’s no real action but it is amusing.

The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan is an enjoyable little story about a greedy money-lender chasing two fabulous emeralds. Literally chasing the emeralds, which ran away from him while he was admiring them. The ending is rather neat. You know that something bad is most likely in store for the luckless money-lender but his fate is not quite the one you might be expecting.

The Theft of Thirty-Nine Girdles is a very late story, originally published in 1958. It’s another tale of thievery and although the methods used by the thieves are highly imaginative they do not quite qualify as sorcery. The thirty-nine girdles are chastity girdles belonging to the sacred virgins of the temple of Leniqua. Virgins is perhaps not an entirely accurate description, the young ladies in question being in fact temple prostitutes. Stealing is a difficult enough art. Ensuring that one actually keeps the rewards of thievery is even more challenging but Satampra Zeiros is a thief of vast experience.

The Coming of the White Worm is perhaps the most ambitious of the Hyperborean tales. And the most successful. A galley is cast ashore. The crew members are dead and when the wizard Evagh suggests that the bodies should be burnt he gets a nasty surprise. The bodies will not burn. Then the monstrous iceberg appears. The iceberg houses a god, a gigantic white worm. The worm makes Evagh an offer he is in no position to refuse although he is by no means certain that this god should be trusted. This is a tale of icy terror, of the horror of the cold that is beyond any natural cold, and the horrors do not end there. Smith was always good with atmosphere but in this story he excels himself. A wildly imaginative and disturbing tale.

The Seven Geases is a dark little tale with more than a tinge of black humour. A magistrate and big game hunter falls foul of an ill-tempered sorcerer who imposes a geas (a kind of magical obligation) upon him. Which seems to lead to more and more geases imposed on the luckless magistrate each o0f which requires him to descend further intro the bowels of a magical mountain wherein he keeps encountering more and more strange and unpleasant creatures. This plot gives Smith the opportunity to really go to town on the atmosphere of dread and malevolence and on the general weirdness. Which he does, to marvellous effect.

In The Testament of Athammaus we learn the exact nature of the fate of the once-proud and now deserted city of Commoriom. Athammaus had been the headsman of the city and was proud of his ability to carry out executions with efficiency and certainty. Only once did he fail in his duty, with awful consequences for the city.

Hyperborea is a mythical world with some similarities to Robert E. Howard’s Hyboria. Hyperborea is a world of wizardry and lost prehistoric civilisations.

In The Tale of Satampra Zeiros two thieves set out to loot the treasures of the lost city of Commoriom, a city shunned by all. The thieves soon find out exactly why everybody shuns the ruined city. The city might be dead but the old gods that had been been worshipped there might not be entirely dead. And they are rather savage gods. There’s more excitement than is usual in a Smith story, there’s a superbly evoked atmosphere of decay and malevolence and there are some definite touches of black humour.

The Door to Saturn is literally about a door to Saturn. The sorcerer Eibon is facing charges of heresy and makes his escape from the enraged inquisitor Morghi just in time. Eibon is a devotee of the god Zhothaqquagh and that deity has provided the sorcerer with a very convenient little door that opens on the surface of the planet Saturn. The only downside is, it he uses the door it will be a one-way trip.

Morghi somewhat unwisely follows Eibon through the door. They find that Saturn is a profoundly strange place. It’s not particularly dangerous, just strange.

This is very much a tongue-in-cheek story with a number of elaborate jokes. There’s no real terror and there’s no real action but it is amusing.

The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan is an enjoyable little story about a greedy money-lender chasing two fabulous emeralds. Literally chasing the emeralds, which ran away from him while he was admiring them. The ending is rather neat. You know that something bad is most likely in store for the luckless money-lender but his fate is not quite the one you might be expecting.

The Theft of Thirty-Nine Girdles is a very late story, originally published in 1958. It’s another tale of thievery and although the methods used by the thieves are highly imaginative they do not quite qualify as sorcery. The thirty-nine girdles are chastity girdles belonging to the sacred virgins of the temple of Leniqua. Virgins is perhaps not an entirely accurate description, the young ladies in question being in fact temple prostitutes. Stealing is a difficult enough art. Ensuring that one actually keeps the rewards of thievery is even more challenging but Satampra Zeiros is a thief of vast experience.

The Coming of the White Worm is perhaps the most ambitious of the Hyperborean tales. And the most successful. A galley is cast ashore. The crew members are dead and when the wizard Evagh suggests that the bodies should be burnt he gets a nasty surprise. The bodies will not burn. Then the monstrous iceberg appears. The iceberg houses a god, a gigantic white worm. The worm makes Evagh an offer he is in no position to refuse although he is by no means certain that this god should be trusted. This is a tale of icy terror, of the horror of the cold that is beyond any natural cold, and the horrors do not end there. Smith was always good with atmosphere but in this story he excels himself. A wildly imaginative and disturbing tale.

The Seven Geases is a dark little tale with more than a tinge of black humour. A magistrate and big game hunter falls foul of an ill-tempered sorcerer who imposes a geas (a kind of magical obligation) upon him. Which seems to lead to more and more geases imposed on the luckless magistrate each o0f which requires him to descend further intro the bowels of a magical mountain wherein he keeps encountering more and more strange and unpleasant creatures. This plot gives Smith the opportunity to really go to town on the atmosphere of dread and malevolence and on the general weirdness. Which he does, to marvellous effect.

In The Testament of Athammaus we learn the exact nature of the fate of the once-proud and now deserted city of Commoriom. Athammaus had been the headsman of the city and was proud of his ability to carry out executions with efficiency and certainty. Only once did he fail in his duty, with awful consequences for the city.

Anything by Clark Ashton Smith is worth reading. Not just a great writer of weird fiction but a great writer of decadent literature as well. Highly recommended.

Wednesday, November 16, 2022

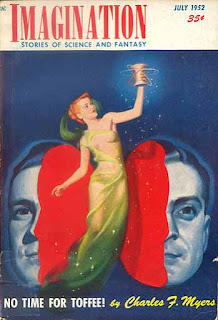

Charles F. Meyers' No Time for Toffee

I know nothing at all about Charles F. Meyers apart from the fact that he wrote a series of humorous science fiction novels about a girl named Toffee. One of these was No Time for Toffee, published in 1952. The fact that he wrote several Toffee books would seem to indicate that they enjoyed some popularity.

The hero of the novel is advertising guru Marc Pillsworth. He’s been shot and is possibly dying. That’s bad news for the High Council. It means that George Pillsworth will be returning to Earth. George Pillsworth is a kind of ghost. He’s the spiritual emanation of Marc Pillsworth. George of course looks exactly like Marc. George can’t stay on Earth permanently until Marc is dead. This annoys him because there are so many things he likes about Earth. There are so many opportunities for dishonesty. There’s good booze. And of course there are women. For a spiritual entity George’s nature may seem to be not very spiritual.

As for Toffee, she’s a smokin’ hot redhead. She’d be the ideal woman if only she actually existed. But she doesn’t. Or maybe she does.

Marc’s immediate problem is that he’s going to have emergency surgery performed on him. The doctors don’t know it but the surgery will certainly kill him. Marc knows this because Toffee told him.

We then get a zany frenetic parade of craziness as Marc tries to avoid the surgeon’s knife, Toffee tries out her new dematerialisation gadget on him, Marc and Toffee try to keep George under control and a crooked congressman tries to have Marc murdered.

This is not science fiction but I guess it qualifies as a comic fantasy novel. The problem with comic novels is that the authors sometimes try too hard for zaniness and this is at times a problem here. It does however have some amusing moments and some moments of inspired lunacy.

It also has some fairly clever ideas. George Pillsworth is a ghost but he’s a totally different and original kind of ghost. He also has the ability to assume genuinely corporeal form. At least he’s corporeal enough to drink whiskey and apparently have physical relations with women. He’s definitely not your everyday ghost.

Toffee is a figment of Marc’s imagination but that doesn’t mean she doesn’t exist. Marc can see her and when she takes on corporeal form other people can see her. When she slugs a bad guy with a whiskey bottle he reacts the way a guy would react if he had been slugged with a whiskey bottle. She can drive a car. She also drinks whiskey (with some enthusiasm). She’s a flesh-and-blood woman but she isn’t real. It’s a cute idea.

By 1952 standards this would also qualify as a slightly risqué tale. There’s some definite sexual humour. Toffee might or might not be real but she’s certainly sexy. She wears very little clothing. In fact her idea of getting dressed for the day is to slip on nothing but an almost transparent négligée and then she’s ready to face the world.

As a character Toffee has a certain charm. She’s cute and feisty and she’s fun when she’s got a few drinks in her.

Whether you’ll enjoy this book or not depends on how you feel about zany screwball humour. If that’s your thing you’ll probably like the book, if it’s not your thing you may find it irritating.

No Time for Toffee is definitely an oddball novel. If you enjoy humorous science fiction/fantasy romps and you’re in the mood for something very light indeed you might enjoy this one.

Armchair Fiction have paired this novel with Kris Neville’s Special Delivery in one of their two-novel paperback editions.

The hero of the novel is advertising guru Marc Pillsworth. He’s been shot and is possibly dying. That’s bad news for the High Council. It means that George Pillsworth will be returning to Earth. George Pillsworth is a kind of ghost. He’s the spiritual emanation of Marc Pillsworth. George of course looks exactly like Marc. George can’t stay on Earth permanently until Marc is dead. This annoys him because there are so many things he likes about Earth. There are so many opportunities for dishonesty. There’s good booze. And of course there are women. For a spiritual entity George’s nature may seem to be not very spiritual.

As for Toffee, she’s a smokin’ hot redhead. She’d be the ideal woman if only she actually existed. But she doesn’t. Or maybe she does.

Marc’s immediate problem is that he’s going to have emergency surgery performed on him. The doctors don’t know it but the surgery will certainly kill him. Marc knows this because Toffee told him.

We then get a zany frenetic parade of craziness as Marc tries to avoid the surgeon’s knife, Toffee tries out her new dematerialisation gadget on him, Marc and Toffee try to keep George under control and a crooked congressman tries to have Marc murdered.

This is not science fiction but I guess it qualifies as a comic fantasy novel. The problem with comic novels is that the authors sometimes try too hard for zaniness and this is at times a problem here. It does however have some amusing moments and some moments of inspired lunacy.

It also has some fairly clever ideas. George Pillsworth is a ghost but he’s a totally different and original kind of ghost. He also has the ability to assume genuinely corporeal form. At least he’s corporeal enough to drink whiskey and apparently have physical relations with women. He’s definitely not your everyday ghost.

Toffee is a figment of Marc’s imagination but that doesn’t mean she doesn’t exist. Marc can see her and when she takes on corporeal form other people can see her. When she slugs a bad guy with a whiskey bottle he reacts the way a guy would react if he had been slugged with a whiskey bottle. She can drive a car. She also drinks whiskey (with some enthusiasm). She’s a flesh-and-blood woman but she isn’t real. It’s a cute idea.

By 1952 standards this would also qualify as a slightly risqué tale. There’s some definite sexual humour. Toffee might or might not be real but she’s certainly sexy. She wears very little clothing. In fact her idea of getting dressed for the day is to slip on nothing but an almost transparent négligée and then she’s ready to face the world.

As a character Toffee has a certain charm. She’s cute and feisty and she’s fun when she’s got a few drinks in her.

Whether you’ll enjoy this book or not depends on how you feel about zany screwball humour. If that’s your thing you’ll probably like the book, if it’s not your thing you may find it irritating.

No Time for Toffee is definitely an oddball novel. If you enjoy humorous science fiction/fantasy romps and you’re in the mood for something very light indeed you might enjoy this one.

Armchair Fiction have paired this novel with Kris Neville’s Special Delivery in one of their two-novel paperback editions.

Wednesday, September 7, 2022

Edgar Rice Burroughs, Pirates of Venus

Pirates of Venus is the first book in the Venus series by Edgar Rice Burroughs, published in serial form in 1932 and in book form in 1934. This was the last of his book series. Compared to the Tarzan, Mars (Barsoom), Carnak and Pellucidar cycles it’s just a tiny bit disappointing. Burroughs was very good at creating imaginary worlds that radically differ from our own world. His world of Venus (the inhabitants call it Amtor) is not quite as imaginative.

Carson Napier is bored with his life. He needs an adventure. So he decides to go to Mars. He’s a keen rocket hobbyist and he is convinced that he can build a rocket that could reach Mars. He builds the rocket and it is launched successfully, with Carson Napier as the sole passenger. Unfortunately he made a mistake in his calculations and he ends up heading towards the Moon instead. The Moon’s gravitational field alters his course and he assumes that he is going to be headed off into the limitless void of space.

Carson Napier is bored with his life. He needs an adventure. So he decides to go to Mars. He’s a keen rocket hobbyist and he is convinced that he can build a rocket that could reach Mars. He builds the rocket and it is launched successfully, with Carson Napier as the sole passenger. Unfortunately he made a mistake in his calculations and he ends up heading towards the Moon instead. The Moon’s gravitational field alters his course and he assumes that he is going to be headed off into the limitless void of space.

But at this point he gets a lucky break. He ends up on Venus.

He discovers that scientists were both right and wrong about Venus. The planet is indeed covered in thick layers of cloud but it is no uninhabitable. He encounters one group of inhabitants immediately, the Vepajans. They live in the trees. Literally in the trees - they live inside the trunks of the trees. These are not like trees on Earth. These trees grow to a height of 6,000 feet and the trunks of some of them have a diameter of 500 feet or more.

The Vepajans are friendly but they warn him not to try to approach the girl in the garden. Naturally he does approach her and he falls instantly in love with her but she gives him the brush-off in no uncertain terms.

Carson gets captured by the birdmen of Venus and after a number of unpleasant experiences he turns pirate. The book then becomes a pretty decent pirate adventure yarn, but in ships that use what sounds like a 1932 idea of what nuclear power might be like.

There’s plenty of action and Carson doesn’t forget about the girl. Despite her coldness he is sure that she secretly loves him.

Apart from the fact that Amtor is not quite as interesting as Carnak or Pellucidar there’s another problem with this book. Burroughs decides to indulge in some political satire. His target is communism. Sadly the satire is incredibly heavy-handed.

Carson Napier is your basic Edgar Rice Burroughs hero, largely interchangeable with all the others. Burroughs had a formula and he stuck to it. He know how to make that formula work and how to produce exciting stories. His world-building could be extraordinarily impressive. Pellucidar remains one of the great fantasy worlds.

Pirates of Venus is entertaining, the city in the trees is a nice idea and like all Burroughs books it’s well-paced.

It’s also worth mentioning that you only get a partial plot resolution at the end. There’s a kind of cliffhanger which sets things up for the next book in the series.

If you’re new to Burroughs then start with the first of Pellucidar stories, At the Earth’s Core, or the first of the Carnak novels, The Land That Time Forgot, or the first of the Mars books, A Princess of Mars. Pirates of Venus is a lesser work. Recommended, if you’re already a hardcore Burroughs fan.

He discovers that scientists were both right and wrong about Venus. The planet is indeed covered in thick layers of cloud but it is no uninhabitable. He encounters one group of inhabitants immediately, the Vepajans. They live in the trees. Literally in the trees - they live inside the trunks of the trees. These are not like trees on Earth. These trees grow to a height of 6,000 feet and the trunks of some of them have a diameter of 500 feet or more.

The Vepajans are friendly but they warn him not to try to approach the girl in the garden. Naturally he does approach her and he falls instantly in love with her but she gives him the brush-off in no uncertain terms.

Carson gets captured by the birdmen of Venus and after a number of unpleasant experiences he turns pirate. The book then becomes a pretty decent pirate adventure yarn, but in ships that use what sounds like a 1932 idea of what nuclear power might be like.

There’s plenty of action and Carson doesn’t forget about the girl. Despite her coldness he is sure that she secretly loves him.

Apart from the fact that Amtor is not quite as interesting as Carnak or Pellucidar there’s another problem with this book. Burroughs decides to indulge in some political satire. His target is communism. Sadly the satire is incredibly heavy-handed.

Carson Napier is your basic Edgar Rice Burroughs hero, largely interchangeable with all the others. Burroughs had a formula and he stuck to it. He know how to make that formula work and how to produce exciting stories. His world-building could be extraordinarily impressive. Pellucidar remains one of the great fantasy worlds.

Pirates of Venus is entertaining, the city in the trees is a nice idea and like all Burroughs books it’s well-paced.

It’s also worth mentioning that you only get a partial plot resolution at the end. There’s a kind of cliffhanger which sets things up for the next book in the series.

If you’re new to Burroughs then start with the first of Pellucidar stories, At the Earth’s Core, or the first of the Carnak novels, The Land That Time Forgot, or the first of the Mars books, A Princess of Mars. Pirates of Venus is a lesser work. Recommended, if you’re already a hardcore Burroughs fan.

Sunday, August 7, 2022

John Norman’s Priest-Kings of Gor

Priest-Kings of Gor, published in 1968, is the third of John Norman’s Gor novels. It differs slightly from the first two books. They had very much the feel of high fantasy with sword & sorcery overtones. Priest-Kings of Gor is more of a science fiction novel.

I’m going to be vague about the plot in order to avoid revealing spoilers for the first two books.

Tarl Cabot is from Earth but he spends much of his time on Gor, which is the Counter-Earth. It’s a planet, almost identical to Earth, within our solar system. Its orbit has made it undetectable from Earth. Gor is also inhabited by humans, identical in every way to ourselves. The differences between the two planets are societal and cultural and those differences are quite profound. Gorean society is hierarchical and divided strictly into castes. Slavery is taken for granted. What made the Gor novels controversial is that on Gor female slavery is taken for granted. Not all the women are slaves, but some are.

Gor is ruled by the Priest-Kings. Nobody knows what kinds of beings the Priest-Kings are. Are they supernatural beings, are they men with supernatural powers, are they men with technology so advanced that they appear to all intents and purposes to be gods, or are they gods? Nobody has ever seen a Priest-King and lived to tell the tale so nobody knows. But the Priest-Kings are feared and obeyed.

In the first two books it was obvious that Tarl Cabot strongly disapproved of many aspects of Gorean society, especially the keeping of women as slaves. In this third book he still disapproves of slavery, but has become more tolerant of Gorean cultural practices.

Now Tarl Cabot is back on Gor and, after the events of the previous book, he wants revenge. He wants to meet the Priest-Kings face to face. More than that, he wants to destroy them.