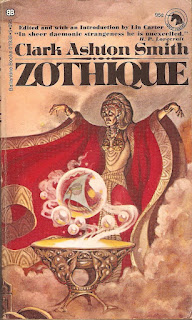

Poet-short story writer Clark Ashton Smith was a prolific contributor to pulps such as Weird Tales in the 1930s. He was part of Lovecraft’s circle of writer friends who kept in constant contact by letter, shared ideas and sometimes settings and influenced one another. The big three of the Lovecraft circle were Lovecraft himself, Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith. They were three very different writers but with a good deal of respect for each other’s work. Smith wrote most of his hundred-plus short stories in the early 1930s.

Apart from being one of the finest of all writers of weird fiction Smith was perhaps the greatest of all American decadent writers. He was certainly the most extravagant prose stylist that America has produced. His stories are lush in a most unhealthy unwholesome way. It is the lushness of decay and degeneracy. Very few writers could match Smith as far as creating an atmosphere of dread was concerned, and none could match him when it came to the seductiveness of evil and the unnatural and perverse.

Occasionally, just to keep us on our toes, Smith would give us a happy ending. Yes, there is a Zothique story with a genuine happy ending. Mostly however things end badly for all concerned. And sometimes he would give us a slightly ambiguous ending. Smith understood that no matter how much a story might be heading towards an apparently inevitable conclusion it is a mistake to allow the reader to know with certainty how the tale will end.

The Zothique stories take place in the very distant future. The sun is now very old and sheds but a feeble light. The last inhabited continent is Zothique. It is a world in which the secrets of technology and science have long since been lost. The level of technology is that of the ancient world. It is also a world of magic. Human civilisation has reached the point of extreme decadence. Cultural exhaustion, pessimism, hedonism and self-indulgence are the hallmarks of human society. This is a society haunted by the glories of the past, and often haunted by the evils of the past as well.

The Last Hieroglyph tells of Nushain the astrologer who is disturbed one day when he notices three new stars in the sky. They are very near to the constellation of the Great Dog, the constellation which presided over his birth. He recasts his horoscope and after poring over his books he decides that it means that he will undertake an unexpected journey, a long journey, and three guides will show him the way. Whether he will find the journey profitable or unprofitable, whether it portends good or evil for him, is beyond his powers to discern.

The journey turns out to be arduous and at the end of it - well you’ll have to read the story to find that out. Suffice to say that Smith comes up with a perfect ending. It’s typical of Smith’s work - clever and imaginative with a sense of foreboding, or at least of unease.

The Empire of the Necromancers tells of two sorcerers who are banished to a wasteland for practising the forbidden art of necromancy. In this wasteland nothing lives, but that’s not a problem for men who can restore the dead to life. They create an empire for themselves, an empire of the dead. They have gained immense power but they are corrupted by it.

This is the kind of story that has gained Smith his reputation as a decadent. It’s a tale not just of a decaying or dying empire but a truly dead one. Smith’s style is rich but it’s the richness of decay.

In The Isle of the Torturers a kingdom is afflicted by a plague. Only the king is immune. With his kingdom destroyed and in despair he sets off on a sea voyage only to find himself on the fabled Isle of the Torturers. On this island torture is the fate awaiting all visitors and the methods of torture are ingenious and fiendish, relying as much on psychological terror as pain. The king’s only chance is a girl who offers to save him.

The Weaver of the Vault is one of Smith’s most anthologised stories. Three men have been sent to a dead city to retrieve a relic, but the dead are guarded well and in a terrifying manner.

The Charnel God is a superb story. In Zul-Bha-Sair the dead belong to the priests of Mordiggian. What happens to the dead is unknown but it’s assumed that they’re devoured by the god. It’s all very unfortunate for a young traveller named Phariom. hIs wife suffers from catalepsy and she’s had another attack. And now the priests have claimed her body. There is of course nothing wrong with her, in the normal course of events she would soon recover, but now she’s going to be devoured by the god. Phariom is determined to save her but it seems impossible.

The Tomb-Spawn is closer to out-and-out horror but as usual with echoes of the past. Two merchants listen to a story about a king from the distant past. He was a king and a sorcerer and he had as his familiar and creature from the stars. The merchants forget about the story and ride on but perhaps they should have remembered the story.

Xeethra is about a young goatherd who discovers a hidden valley. But what has he really discovered? Has he entered the past or a world of dream and illusion, and is he really a humble goatherd. This is a particularly evocative and subtly disturbing tale.

In The Dark Eidolon a young beggar-boy is trampled under the hooves of the horse of Zotulla. The beggar-boy survives and later, in a distant land, becomes the notorious sorcerer Namirrha. Zotulla becomes the king. Namirrha still wants his revenge and returns to the city of his birth for that purpose. He calls upon dark powers to aid him, but that can be a dangerous thing to do. Especially if you have the arrogant belief that you compel those powers of darkness to do your bidding.

In The Black Abbot of Puthuum two warrior have to escort a eunuch to a distant town. There’s a rumour of a particularly beautiful girl living here ad the eunuch is to buy her for his king. They buy the girl but on the return journey they encounter a strange wall of darkness then an isolated monastery. The abbot, a huge black man, has a sinister air about him. That monastery turns out to be a very bad place to visit. Another tale of evil from the distant past, with an ending which is not what you expect from Clark Ashton Smith.

In Necromancy in Naat Prince Yadar searches for his beloved Dalili, stolen by slavers. His quest takes him to the dread island of the necromancers of Naat. Does he find what he is seeing? Well, yes and no.

The Death of Ilalotha is a story of love, of sorts. Ilalotha, lady-in-waiting to Queen Xantlicha, is dead and is laid out on her bier whilst the traditional mourning orgy takes place. Lord Thulos had been her lover but he had abandoned her in favour of the queen. Ilalotha, who was rumoured to dabble in sorcery, took her defeat in love rather badly. Now Lord Thulos has returned from a journey, and he has the odd impression that perhaps Ilalotha is not truly dead. Love and passion usually do not end well in Clark Ashton Smith’s stories.

The Garden of Adompha is a nicely macabre tale. The garden belongs to the king. Only the king and his chief sorcerer have access to the garden. And very strange things happen in that garden. Things grow there that should not grow anywhere.

Morthylla is about a young man who has sampled all of life’s pleasures and he is now suffering from ennui. He needs stronger pleasures. It is suggested to him that if he visits a nearby necropolis he will encounter a lamia, and that she may introduce him to pleasures sufficiently perverse to meet his needs. Of course since she’s a lamia those pleasures might be fatal. He goes to the necropolis and meets a beautiful woman there. But is she the lamia?

Every single one of the Zothique stories is very very good. The Zothique cycle was an astonishing and unique achievement. There’s nothing else, in any fictional genre, that has quite the same flavour. Very highly recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment